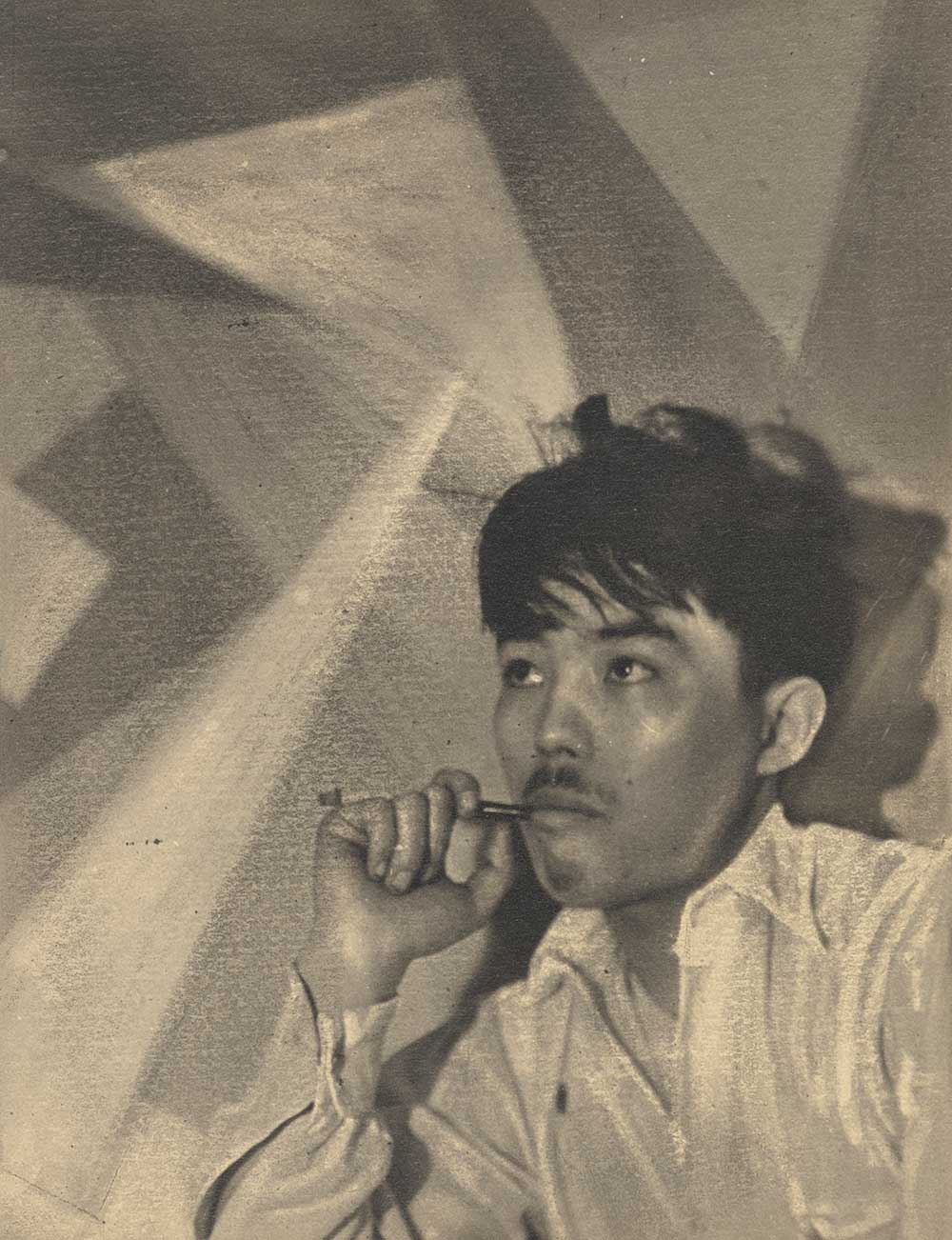

Cut-paper abstraction, by Francis Bruguière, c. 1927. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

To begin, if not at the beginning, early on: the painter and poet David Jones resumes his studies at the Westminster School of Art in his mid-twenties, not long after his service with the Royal Welch Fusiliers in World War I ended. The 117 weeks he spent in a war that shattered so many millions shattered Jones no less, though the full extent of his brokenness would not appear until over a decade later, in 1932, when the first of two major nervous breakdowns would interrupt work on his first great long poem, In Parenthesis, and keep him from painting for years. As Jones would later suggest, every aspect of his life seemed to revolve around the dilemma that the war had either caused or, as he would come to believe, merely revealed: that modern life was fundamentally fractured. It was up to the artist not so much to heal those fractures as to discover a way of navigating them and in so doing find a way of being at home among them.

He fell under the tutelage of a charismatic teacher as well as in love with an alluring classmate; both were Roman Catholic. Through these connections, as well as through characteristically idiosyncratic reading (medievalist Jessie Weston and anthropologist James Frazer, among others), Jones came to consider Catholicism for himself and became acquainted with Father John O’Connor, an Irish priest in the process of translating the works of the French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain.

Sensing the young painter’s state of mind, O’Connor recommended he visit Ditchling. In this Sussex village, the sculptor and engraver Eric Gill had created with his family and a band of Catholic artisans a commune and craftsmen’s guild called the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic. The guild operated under the principles of distributism—a strain of antistatist socialism derived from Catholic social teaching—and drew inspiration from the Arts and Crafts movement of a generation earlier. Important above all for Gill, a social critic as well as an artist (his sexual crimes were largely hidden during his lifetime), was that artists consider themselves craftsmen and behave as such, insisting on orderliness and diligence, as well as the neglect of anything that smacked of artistic pretension. The group summed up its purpose with a motto: “Men rich in virtue studying beautifulness living in peace in their houses.” Its appeal was undeniable for anticapitalists horrified by the increasingly swift destruction of working-class life and yet skeptical of state socialism, which seemed to change only who was in charge of the encroaching technocracy, the term Jones would later use to define capitalist modernity. Jones eventually moved to Ditchling after abandoning his studies at Westminster. He apprenticed himself to a carpenter; after proving to be, in his words, “a frightful carpenter, the worst carpenter in the world,” he devoted himself to engraving and watercolors.

Jones would go on to become a painter, a poet, an engraver, and an essayist of extraordinary skill, inventiveness, and sensitivity. His work was praised in the strongest possible terms by W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot, and Igor Stravinsky. He also became, following his death, one of the more frustrating examples of artistic obscurity. Subject to frequent revival attempts—most recently during the centenary years of World War I, with a series of Faber & Faber reprints, a biography, and gallery and museum exhibitions—his work is a catalogue of curious, beguiling engravings and letterings; breathtaking landscapes and still lifes in eddying watercolor; and dense, disjointed poems of haunting beauty. Yet for all the variety, there is a clear thread running through Jones’ oeuvre that begins to look like the heart of a single ongoing effort to deepen a communion with something that seems at all times present and yet elusive.

It was in the shabby yet stimulating surroundings of the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic that the seeds of the vision Jones would spend the next half century realizing first took root. And perhaps the central preoccupation of his artistic life, the relationship between art and religion, especially Catholic Christianity, was indelibly marked by an early encounter with Gill.

In David Jones: Engraver, Soldier, Painter, Poet, Thomas Dilworth, a prolific and perceptive scholar of Jones, explains how Gill finally convinced the younger artist to convert to Catholicism while on a visit to Ditchling in 1921. After making a few declarations about the moral and doctrinal authority of the Catholic Church, Gill drew three triangular shapes, only the last of which was connected at all three points. When asked to pick out the triangle, Jones said, “I like that one,” to which Gill replied, “I didn’t ask which you prefer. That isn’t a better triangle. The others aren’t triangles at all. Either it’s a triangle or it’s not.” Though the story has been told in several biographies and studies, Jones reported his own interpretation of the event directly to Dilworth: it was this exchange that convinced him to convert to Catholicism.

Dilworth notes that Jones’ parents met their son’s decision with dismay, with his evangelical father calling it “the Romish Church.” Anti-Catholicism had been in a long decline since the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, but while the Oxford Movement, a group of theologians who laid the foundation for what would become Anglo-Catholicism, had generated many conversions and a certain amount of prestige, those of the faith remained a somewhat suspect minority, associated with eccentric intellectualism, dubious ritualism, and uncertain political allegiance. Already a bohemian artist with a profound sense of the sacred, the young Jones was drawn to Catholicism both for its avowed continuity with antiquity and the participatory nature of the sacraments. For the aspiring artist, to become a member of the Catholic Church was to seize upon a new mode of creativity, and to discover a deep well of materials with which to exercise it.

But there is in Gill’s example another lesson, which became clearer as Jones grew older and lies at the heart of the pair’s eventual disagreement: that the meaning of the completeness of the full triangle is realized in contrast to the broken ones. However much Gill insisted that it was the only triangle, those defective shapes were nevertheless recognizable as what they were meant to be; the mind traces the missing lines, lending them a clarity their material construction lacks. In slightly more theological terms, while religion reaches toward the perfection of the eternal, it does so through the finitude, the contingency, even the brokenness of the given world. As Jones developed as an artist and as a religious person (the two were inseparable, at times even indistinguishable, for him), it was the paradoxical interdependence of the broken and the perfect that defined his efforts. To build upon this insight as an artistic principle allowed him an aesthetic vision born out of the dynamic possibilities of religious life, not the petty moralism that, as Jones came to believe, even Gill tended to indulge in. (The irony is that while Jones was by all accounts a rigorously ethical man, nonjudgmental of others yet protective of his own chastity despite the great emotional cost, Gill’s diaries posthumously revealed endless extramarital affairs, sexual abuse of his daughters as teenagers, and experiments in bestiality.) Jones never sat entirely comfortably as Gill’s disciple, and as he grew older and more confident in his convictions, he more frequently voiced disagreement with his former teacher’s views. But the two never ceased to be close friends, and the relationship remained for Jones a decisive one.

Jones’ perspective—though a stronger word seems called for, maybe faith—provided for him a certain concreteness, an earthy vitality that is most palpable in his watercolors, their profound sense of light and form seeming to traverse the boundary between the figural and the abstract. He considered the distinction between the two categories to be totally untenable, believing that while every painting is held together by an idea and so ultimately abstract, the act of representation is in its deepest sense not a depiction but a literal re-presentation, a new manifestation of a given thing. In his most important essay, 1955’s “Art and Sacrament,” Jones wrote, “The painter may say to himself: ‘This is not a representation of a mountain, it is ‘mountain, under the form of paint.’ Indeed, unless he says this unconsciously or consciously he will not be a painter worth a candle.”

Theologian and former archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams has attributed this concreteness to Jones’ commitment to the surface, by which he rejects the usual figurative dependence on depth in favor of a linearity that requires continual reappraisal even to come to terms with what is being depicted. His images produce a deferral and diffusion of interpretive effort that holds the viewer at the first moment of encounter while building significance through almost meditative repetition. This is particularly clear in his inscriptions, which were most often in Latin and Welsh with oddly inserted line breaks, both of which serve as stumbling blocks to any straightforward deciphering. But it is equally present in his watercolors, in which figures swirl almost magically on the surface. See, for example, his 1929 painting The Terrace, in which distant steamer ships, the sea, and a covered terrace are depicted not with geometric accuracy but rather as they might be seen in a moment of epiphany. The viewer might wish they were on one of those ships; perhaps the sea overwhelms them as it vanishes at the horizon; perhaps they are pleased by the flowers in the vase. These possibilities seem to collapse into one another just as the visual field does into itself, out of which a clarity emerges: the viewer is simply there, overlooking the terrace, overlooking the sea.

In Grace and Necessity: Reflections on Art and Love, Williams unfurls Jones’ method with a description of Y Cyfarchiad I Fair, which sets the Annunciation in the Welsh countryside, showing how the painting both depicts a religious event and, in the strictest sense, is a religious event as well. In this watercolor painting, “the birds are not a naturalistic or even symbolic-naturalistic background for Mary’s spiritual encounter…they are the mobile life of an actual landscape that is being ‘relit’ by the nonlocal but utterly concrete presence of the coming Word of God.”

In the lengthy preface to his masterpiece, the 1952 poem The Anathemata, Jones wrote, “It may be that the kind of thing I have been trying to make is no longer makeable in the kind of way in which I have been trying to make it.” This dense, lengthy, formally challenging modernist epic draws on a range of sources both obscure and well-known, from myth to geography, altar to trench. Its premise, brought to life over the course of 250 pages, is the thoughts that run through the mind of a British parishioner during a certain stretch of the Latin Mass. And while it may be, as Auden called it, “the finest long poem in English in [the twentieth] century,” I think it would be wrong to say that it is therefore perfect or even always a pleasure to read. Such praise might mislead us in trying to think through what seems to me to be at the heart of the poem, namely, a grappling with the question of whether its very existence—as poem, in all the historical, cultural, and spiritual significance that word implies—is even possible.

Impossibility hangs over The Anathemata like a specter. The lyric and the fragmentary play off one another in the same way that the figural and the abstract—to pretend, for the moment, that this distinction that Jones showed to be dead is actually alive and may serve some purpose—play in the visual work, offering hope of solidity in the face of loss while at the same time accentuating the pathos of loss by so masterfully displaying what once was or could more easily have been. Dilworth may be right when he suggests that the poem is the first epic to successfully replace narrative with structure, but neither narrative nor structure supply unshakable ground. Both require communal assent and, on some level, participation. If the reader or viewer is no longer capable of seeing or discerning either element, then the question is not so much whether the structure has been successfully erected or the story well told as it is whether such a question can even be asked.

What is in question is what Jones called the “validity of signs,” that is, the ability to make and receive meaning out of the material of experience. But the paradox of modernity for Jones is that while the validity of signs is in question, sign making remains the fundamental human activity; it is what marks a thing as human and indicates the special human relation to the divine. The Anathemata is an instance of sign making in the era of the questionable sign. In attempting to speak truly to that era, the poem is also a response to its most pressing challenge, namely, how to affirm the validity of the sign in such a way that speaks to the contemporary experience of any sign, that is, as invalid.

The question of validity is one Jones shared not only with his modernist peers but also with the best of his Victorian forebears, such as the Arts and Crafts movement associated with William Morris and John Ruskin, of whom Eric Gill was a latter-day representative. For these Romantic socialists, the Industrial Revolution had exacerbated the crisis endemic to capitalism, namely the reduction of all human life to the processes of commercial exchange. The rise of the machine, as Morris put it in 1883’s “Art Under Plutocracy,” did not reduce labor, but rather reduced only the cost of labor. This development was evidence not only of an ever-greater distance between workers and the value of what they produce but an ever-diminishing possibility of doing anything for any reason other than profit. A correlative crisis in the arts cut what Morris called “intellectual” artists off from the traditions that provided them with their vocabulary, to say nothing of the public they ostensibly tried to reach, while the “decorative” arts had become utterly moribund, even ugly. The response, in line with a “reconstructive” socialism, was to rediscover natural enthusiasm in the making of beautiful and useful things. As Morris put it, paraphrasing Ruskin, “Art is man’s expression of his joy in labor.”

Though in almost diametric opposition to that of these Victorians, Jones’ work resonates with the great Modernist poets of fragmentation, such as Eliot and Ezra Pound. Jones admired Eliot, and though he hadn’t encountered Pound before writing The Anathemata and was irked by the comparisons made upon its publication, he liked The Cantos when he finally did read it. The imaginary landscape these poets occupied is one Jones seems to have shared: Eliot wrote in The Waste Land, “These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” while Jones quotes the Welsh antiquary Nennius, “or whoever composed the introductory matter to the Historia Brittonum” with “I have made a heap of all that I could find.”

Jones sits between these two camps, offering an unlikely but compelling synthesis of both the Victorians’ and modernists’ most enduring qualities. Uniting them all is a concern, if not a preoccupation, with what Jones would call “the Break,” which he articulated—somewhat elliptically—as an ineradicable change in the way people in the modern West live their lives, affecting all levels of relation from art and religion to politics and commerce. In the preface to The Anathemata, he wrote, “Most now see that in the nineteenth century, Western Man moved across a Rubicon which, if as unseen as the thirty-eighth parallel, seems to have been as definitive as the river Styx.” Reading Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West, which theorized inevitable cycles of flourishing and decay for every culture, the end of the nineteenth century being the final days of the Western, “Faustian” civilization, gave Jones a somewhat harder edged perspective. But he was kept from total cultural despair both by the Victorian humanism he derived from Gill and by his Catholicism, rich as it was with a sacramental metaphysics that deemed everything already participating in the divine, that is, mysteriously, already saved. The Break, then, is not an event inaugurating the modern, which can either be overcome or else endlessly lamented. For Jones, the Break is the modern or, at the very least, its animating logic. His Catholicism imbued him with the hope that even the invalid sign could be redeemed—not in its reconstruction as something that it was supposed to be but in its finite particularity, in how it really was.

Tellingly, it was James Joyce and Pablo Picasso Jones seems to have revered most among his contemporaries. He considered them artists almost out of time, as though visitors from a less fragmentary epoch, were they not so responsive to the fine grains of their historical circumstances. As with Joyce and Picasso, it was not enough for Jones, as Eliot writes in Four Quartets, “to kneel / Where prayer has been valid,” but rather to unearth and explore what validity is possible in his own day, to test whether the thing he wants to make is really makeable.

If this all sounds too abstruse, too abstract, that’s not altogether a bad thing: Jones’ work often seems like a difficult idea, constantly on the verge of slipping out of your grasp. Everything comes back to the experience of making things, to careful, undivided attention that is still able to hold in its eye the particular joint, the particular stroke, the particular line, and also the house, the painting, the poem. There is also anxiety and doubt equally present in the most carefully made thing, a look over one’s shoulder for a last glimpse at what seems, but may not be, complete. But perhaps what was lost might be salvaged and seen in a new frame or used to turn the eye to a larger body of work or a small, consequential detail. This, for Jones, is what we must come to terms with in our historical memory, in our daily making and maintenance, in our striving for God: the heartache and the hope of the lingering glance.