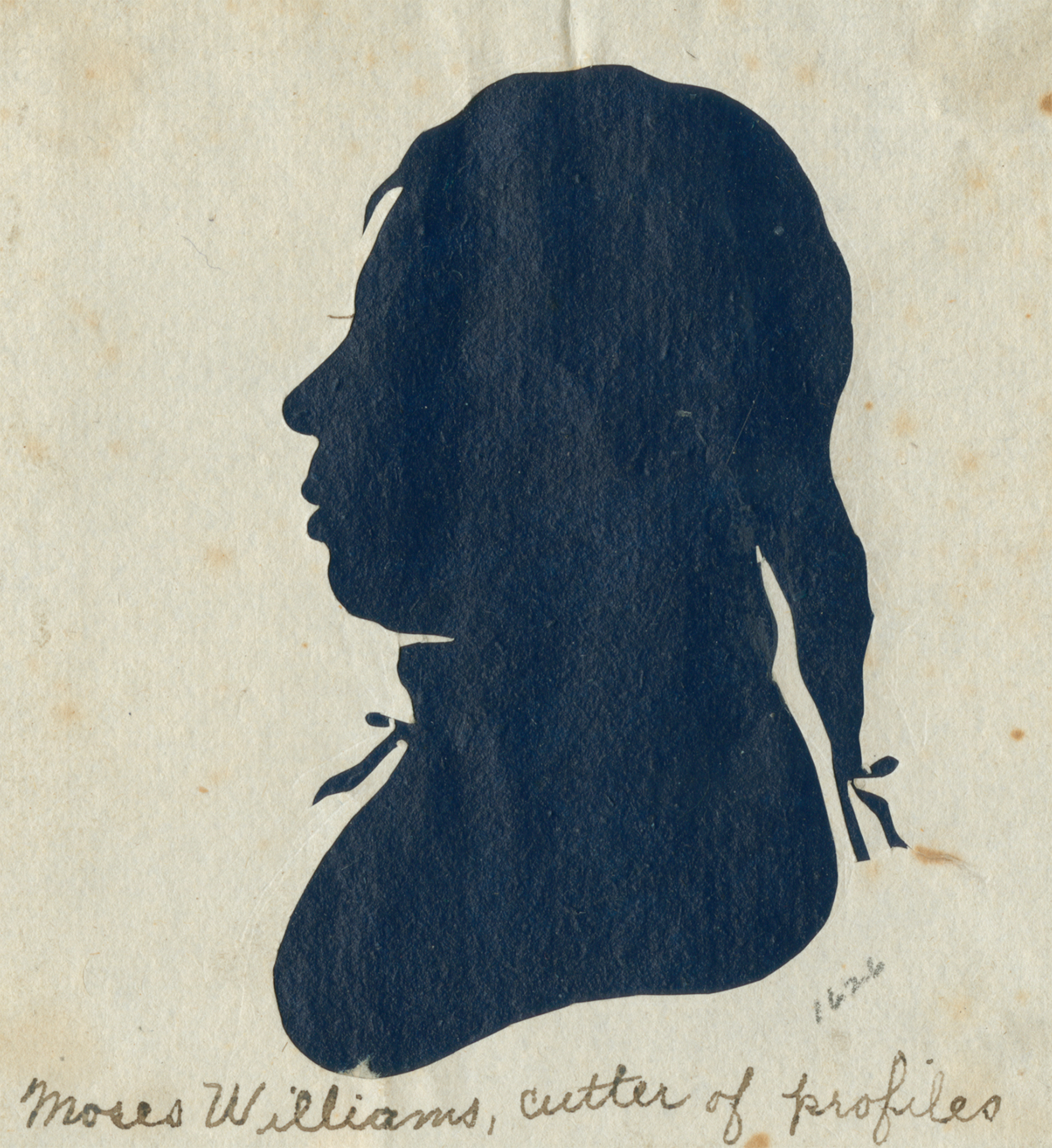

Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles, by Moses Williams and Raphaelle Peale, c. 1803. The Library Company of Philadelphia.

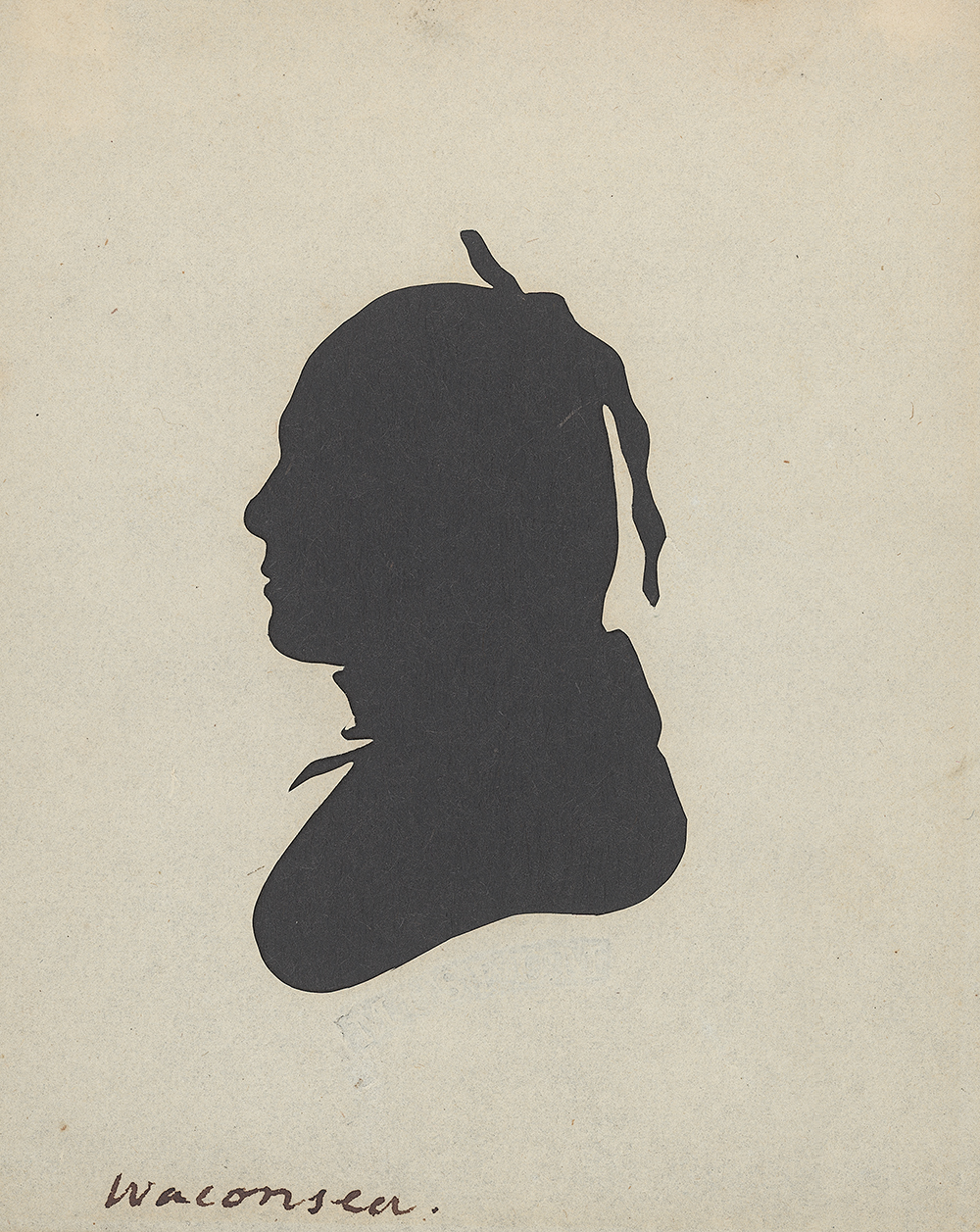

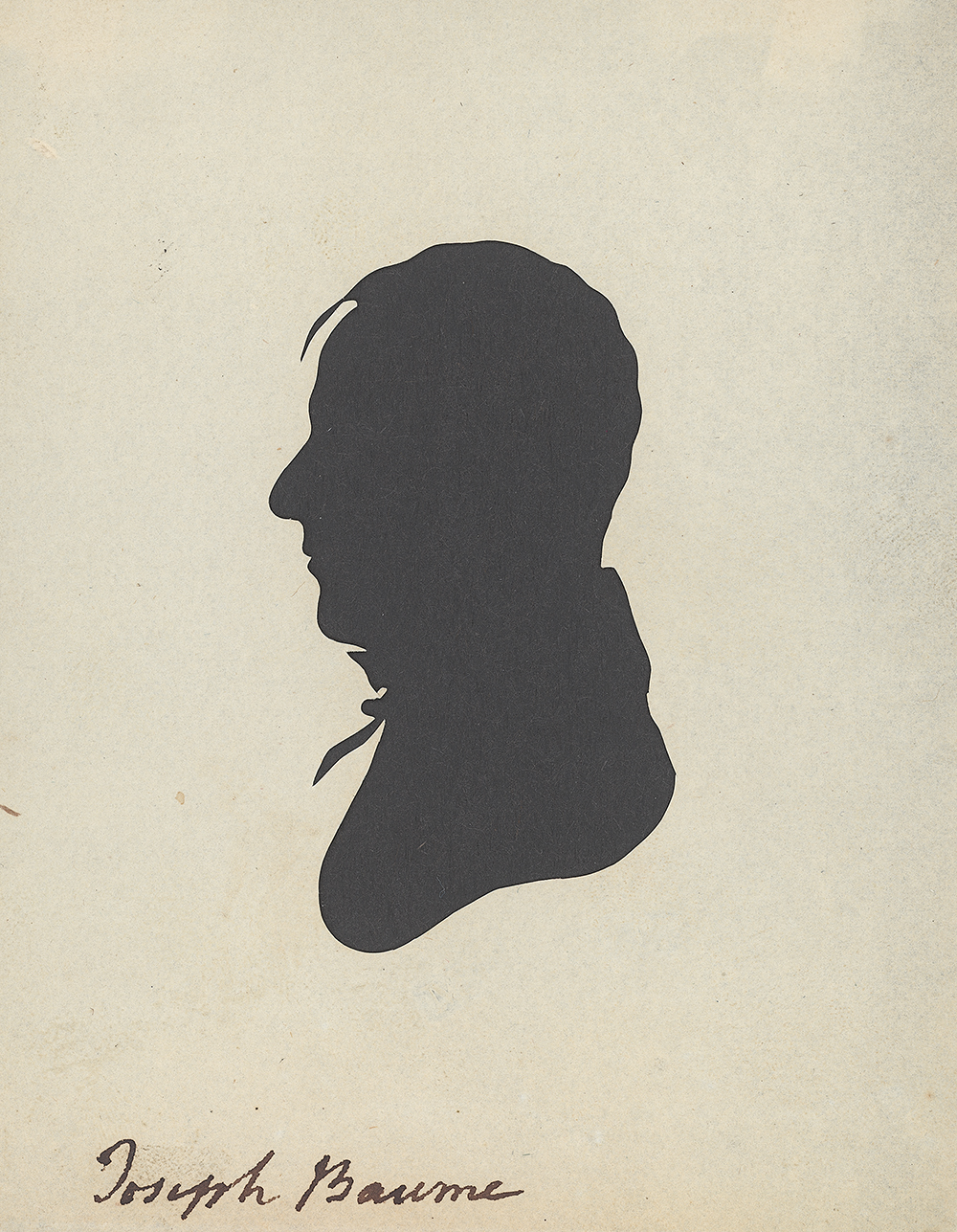

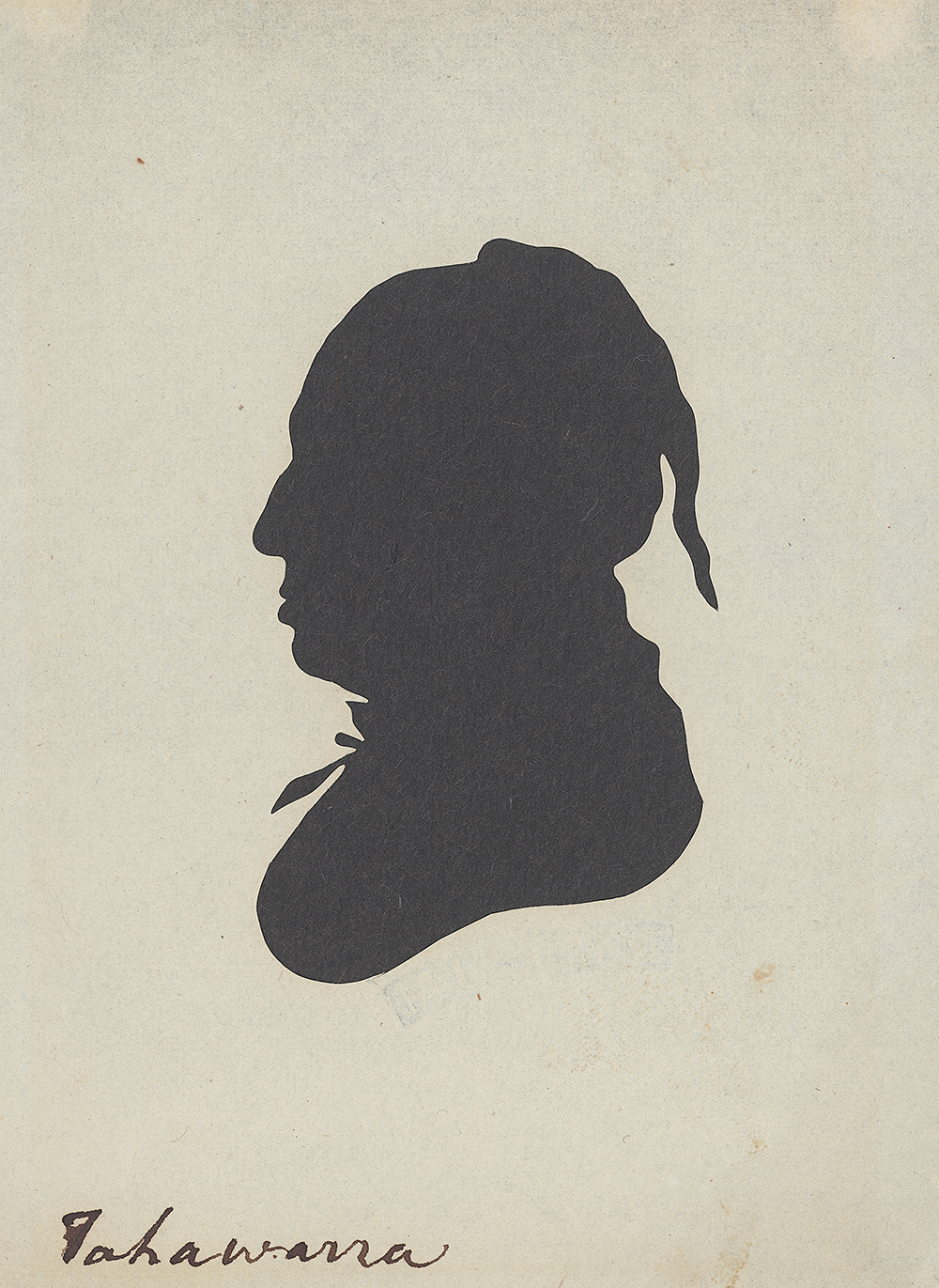

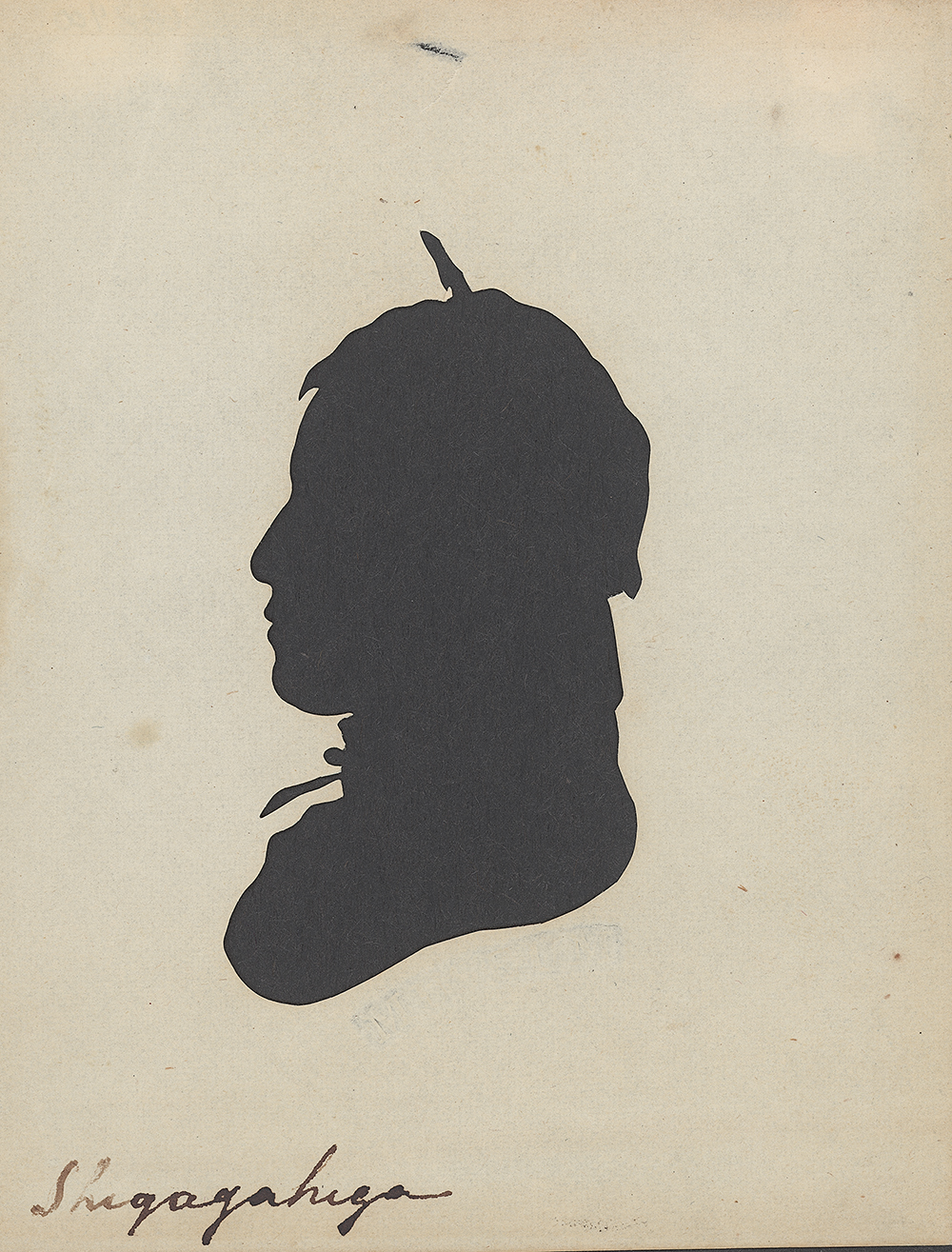

In February 1806 a young Native American man called Wasconsca from somewhere west of the Mississippi sat on a chair in the second-floor “long room” of the State House in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, that housed Charles Willson Peale’s museum. He kept his head still for the minute or so that it took Peale’s formerly enslaved, mixed-race assistant Moses Williams to use a tracing device with an articulated arm called the physiognotrace to reduce and then transfer the lines of his profile onto a piece of twice-folded paper. The surviving example from the original set of four silhouette portraits that were cut that day reveals a striking profile. The cut line denotes the facial features of a well-formed young man with a high forehead, smooth brow ridge, and strong jaw; a lock of hair is pulled back from the face and tied high, with a feather ornament thrust into its cinch; it finishes with a high-collared coat and neckerchief. The coat, in seeming competition with a lush flow of hair at the nape of his neck, juts out at the back, making him appear broad-shouldered and thickly muscled. But for the unusual arrangement of the boldly ornamented hair, Wasconsca’s portrait might be mistaken for that of a European-descended sitter, such as the French Canadian interpreter Joseph Barron, who traveled with the delegation of Native Americans of which Wasconsca was a part. It is this attention to what we would today call the ethnographic details and accoutrements of cultural difference that gives this small five-by-three-inch hollow-cut silhouette portrait profile its visual power.

A tool that was specifically designed for image making, the physiognotrace was closely related to the polygraph, a mechanized writing aid, which held two quill pens, that was used to make two copies of the same document at once. Both machines were codesigned, constructed, and promoted by Peale, who marketed them to other men of letters, including President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson owned a polygraph, which he used to make personal copies of his letters and other writings, thereby eliminating the need for an amanuensis and increasing the level of privacy surrounding his communications. These two devices aided their users by enabling them greater control over the production of both visual and textual meaning via modes that ensured precise, scientific duplication. The physiognotrace helped to precipitate a revolution in representation by offering inexpensive, portable, and accurate profile portraits for sitters.

At Peale’s museum, Moses Williams both traced and cut the vast majority of the profile portraits that were made using the machine, although some of the sitters cut their own. “It is a curious fact that until the age of twenty-seven, Moses was entirely worthless: but on the invention of the Physiognotrace, he took a fancy to amuse himself in cutting out the rejected profiles made by the machine, and soon acquired such dexterity and accuracy, that the machine was confided to his custody with the privilege of retaining the fee for drawing and cutting,” Peale’s son Rembrandt later recalled. “This soon became so profitable, that my father insisted upon giving him his freedom one year in advance. In a few years he amassed a fund sufficient to buy a two-story brick house, and actually married my father’s white cook, who during his bondage, would not permit him to eat at the same table with her.” Throughout his lifetime, both before and after his (early) manumission, which came in 1804, Williams depended on Peale’s benevolent largess to sustain himself and his family.

The derisive tone of Rembrandt’s recollection points to the climate regarding race, labor, and representational skill that circulated in Peale’s museum during the first decades of the nineteenth century. Similar racial sentiments, this time from a sitter, may be ascertained in an 1803 letter that Peale wrote to another son, Raphaelle, who was then using a similar physiognotrace to make profile portraits of sitters in Virginia. “I have just spoken to a Gentleman who says he was at your Room in Norfolk which was so crouded [sic] that he could not get his profiles,” Peale wrote to Raphaelle. “Moses has made him a good one, being from Carolina he did not at first relish having it done by a Molatta [sic], however I convinced him that Moses could do it much better than I could.” Over the next two decades, Williams would cut tens of thousands of profiles for visitors to the museum. And yet, despite his high level of skill and remarkable productivity, curators have historically resisted attributing profile portraits of notable figures made at the museum to him. Often, they have inscribed Peale’s identity (or that of his son Raphaelle) over that of the formerly enslaved employee. In so doing, they have wittingly ignored Peale’s supervisory role as the proprietor of the museum and obscured Williams’ professional function as its “cutter of profiles.”

Whether living as an enslaved person with the Peale family or as a freed householder, Williams spent his life negotiating his visible difference from the dominant population of white Philadelphia. The 1820 census, for example, found him and his mixed-race family in the Lower Delaware Ward of Philadelphia, an area bounded by the modern Race Street, Arch Street, North Fourth Street, and the Delaware River. In 1820 the ward contained 3,143 whites and 94 free blacks, and it only contained three black households—just two others besides that of the Williams family. Nearly all the other people of color in the neighborhood resided in those households as servants. Remarkably, ten years earlier in the 1810 census, Williams was listed as living in the adjacent North Mulberry Ward (covering a similar area stretching two blocks north from Arch Street to Vine Street), but in this enumeration, the entire Williams family is listed as white.

Just as his ambiguously raced body made it difficult for census enumerators to record Williams’ identity with consistency, it also enabled him with the right costuming to inhabit multiple guises of otherness, including that of a Native American. In addition to cutting silhouettes, he was also called upon on occasion to dress up as an Indian and parade through the streets of Philadelphia passing out handbills advertising the many attractions on view at Peale’s museum. Williams had to negotiate complex networks of racial bias that were brought to the museum by its many visitors. What must he have thought, then, when Native American representatives from west of the Mississippi arrived at the museum to sit for their portraits?

Having stopped first in Washington, DC, in December 1805 and January 1806 to meet with Thomas Jefferson, the 1805–6 Indian delegation that included Wasconsca and Barron was the third group of Native peoples from west of the Mississippi to arrive in the young nation’s capital. The first of these groups had received an invitation to visit Washington, DC, and meet the president in 1804 when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark first arrived in Saint Louis, in the new territory of Missouri, on their expedition of exploration and diplomacy, which followed the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Over the next few years, at the behest of Lewis and Clark, dozens of Native American emissaries from as far west as Sioux territory, in what is now Wyoming and the Dakotas, would make their way east to Washington, DC, to meet with Jefferson and his representatives.

The first delegation of Native emissaries from west of the Mississippi arrived in Washington, DC, in July 1804. After being welcomed into the city and meeting the president, they were then persuaded to sit for physiognotrace drawings made by Charles Févret de Saint-Mémin that are now in the collections of the New-York Historical Society. While the Peales used the physiognotrace to create small-scale, hollow-cut profile portraits, making four at a time by folding a piece of paper in half twice, Saint-Mémin used the device to make life-size single images of his sitter’s profile view. The artist would then fill in the details of the sitter’s face, hair, clothing, and accessories. If physical and costume-related details, like eyelashes or hair ornaments, might be hinted at through details penned onto the surface of the paper that remained following the cutting of each Peale physiognotrace silhouette, Saint-Mémin’s uncut and painstakingly enhanced profiles allowed for infinitely more detail about the appearance of the sitter to be added.

In both portraits, Saint-Mémin has chosen to finish his work by adding Conté crayon and white chalk details to enliven the composition and highlight certain novel features of the sitter while allowing elements of their appearance that would be more familiar to nineteenth-century white viewers, like military coats, to remain, but only sparely defined. It is a strategy of visual representation that undergirded a prevailing belief in both the anachronistic status of Native Americans—seeing them as a people outside of biblical and contemporary temporality—and a belief in their inability to assimilate (rather than a dislike for the act) into the newly imposed European-style society that was rapidly encroaching upon their communities.

In 1806, when Moses Williams made hollow-cut profile silhouette portraits of Wasconsca and his fellow delegates during their visit to Philadelphia, his former master, Peale, took both cultural and scientific interest in detailing the physical and cultural differences of the Native American visitors that could still be ascertained. The letter from Peale to Jefferson that accompanied the group of eleven silhouettes, nine of Native American sitters and two of European Americans, reveals similar representational concerns. Here, Peale expressed his hope that the enclosed profiles would be “acceptable” and that the names written on them (in an unidentified hand that may be that of Moses Williams) “may not be correctly spelt.” He also wrote that “some of these savages have interesting characters by the lines of their faces.” This observation referred to the contemporary pseudoscience of phrenology, which was based on the belief that neural anatomy was expressed in the shape of the skull—in its curves, planes, and bumps—and that the deviation of these measurements from a norm could give insight into an individual’s or an entire ethnic or entire racial group’s level of intelligence or even their criminal propensity.

Even though as an elected state legislator, Peale campaigned for the eventual abolition of slavery in Pennsylvania, in practice he remained remarkably ambivalent about its usefulness. While there is little extant documentation of his slaveholding, which may have been purposefully destroyed, he may have received Williams’ parents, a mixed-race couple named Scarborough and Lucy, as payment for portraits he painted in Maryland during the period leading up to the Revolutionary War. Shortly thereafter, in 1777, Moses was born to the couple, and following the condition of his mother, he became Peale’s property. Had Moses’ birth come just three years later, when the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery passed the Pennsylvania legislature (with Peale’s assistance), he would have been born free. After the act’s effective date of March 1, 1780, Moses’ status now fell into the category of indentured servitude, which allowed Peale to hold him until his twenty-eighth birthday. To Peale, Moses Williams was a “Molatta,” belonging on a lower stratum in the order of mankind, one that may not have deserved to be enslaved for life but certainly could be subordinated and controlled, treated in the same manner as one would a child.

In addition to being the workspace of Williams, who could be ordered to dress up in Native American garb when not operating the physiognotrace and cutting silhouettes, Peale’s museum held Native American artifacts and human remains. On the day that Wasconsca sat for his portrait at the Philadelphia museum, not only would he have encountered Williams’ ambiguous body, he would have also seen on display the skeletons of a man and a woman who had once been members of the Wabash confederacy. Whether it was Wasconsca and his compatriots or the deceased Wabash, like their African-descended counterparts who were at the mercy of an insidious, European American–dominated patriarchal structure, Native Americans of the period had little control over the way that they were imaged or explained in the white man’s historical record.

Excerpted from “Interesting Characters by the Lines of Their Faces” by Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, in Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now by Asma Naeem. Copyright © 2018 by Smithsonian Institution. Published by Princeton University Press, Princeton, and Oxford in association with the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC. All rights reserved.

Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now is on view at the National Portrait Gallery until March 10, 2019.