Väinämöinen Playing, by Robert Wilhelm Ekman. Finnish National Gallery.

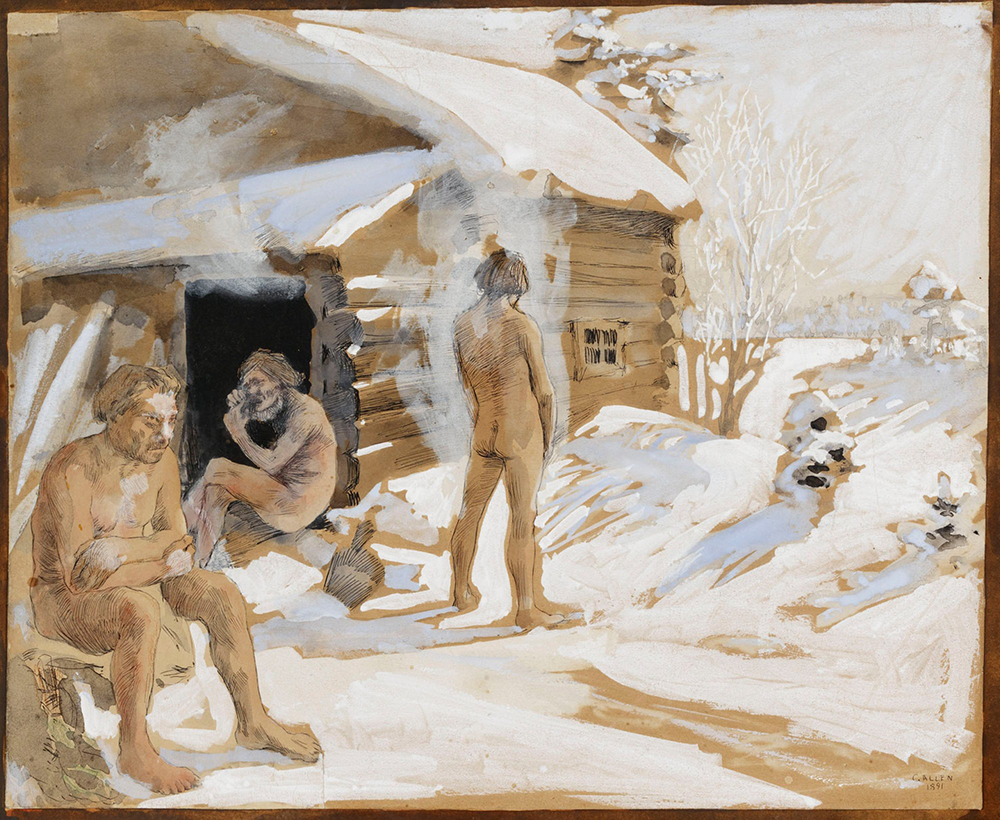

It’s rune number forty-five of Finland’s national epic, the Kalevala, and Loviatar, daughter of the god of death, is in a sauna, where she has just given birth to nine boys. According to lore, Loviatar was impregnated by the wind, in a virgin conception of sorts. Now, in the extreme heat, she bestows names on her fiendish spawn. These correspond to their roles in the grim familial calling of death: Consumption, Colic, Gout, Rickets, Ulcer, Scab, Cancer, and Plague. (The ninth son is the evilest of the brood and so, as befits great evil, remains nameless.) This new, malignant generation emerges from the sauna ready to wreak havoc, and Loviatar promptly dispatches her nine newborn hellions to Kalevala, the mythical Finnish city from which the epic takes its name, where they set about attacking its populace.

The people need a protector, and it sounds like a job for Väinämöinen, the leading man of Finnish mythology—godlike, wise, and a renowned singer of poems. The task of defending the citizenry of Kalavela falls to this national hero. Väinämöinen predates the world, having helped create it. He now steps into the role of savior—and how else but by harnessing the very power source that helped create the problem? Enter the sauna.

During the medieval saga age, the sauna was, as it commonly is now, a cramped wooden chamber heated to an unforgiving 190 degrees Fahrenheit by a wood-burning stove sheathed in a bed of rocks. In the Kalevala Väinämöinen proceeds in his mission by beckoning, from his sauna’s wooden perch, to Ukko, the pagan god of weather and sky. “Come now,” Väinämöinen calls, “into the löyly, God!” As used in the verse, the word löyly is ambiguous. It can refer specifically to the sauna’s expulsion—the steam produced by throwing water onto the stove’s rocks—but it can also mean the general act of taking a sauna. Perhaps the term here means Väinämöinen has invited the god to take a sauna with him so that they might hatch a plan. It is more likely, however, that he has entreated Ukko to save the city by imbuing the löyly, or billowing steam, with plague antidotes and colic remedies; the sauna’s steam would deliver these protections to the citizens of Kalevela as it spread through the city’s atmosphere. The text does not specify. But what is made clear is that Väinämöinen is granted the necessary remedies, which he administers to the wounded and suffering, averting disaster. The Finns live on.

Originally a set of oral poems sung down through generations in various related traditions throughout the region—some verses perhaps thousands of years old, some more recent—the Kalevala was saved from extinction by the nineteenth-century physician and philologist Elias Lönnrot, who compiled and transcribed as many poems as he could collect, preserving them in all their vernacular glory, culminating in the 1849 publication of a “new” Kalevala. The language of this text is often inaccessible and regularly stumps readers today. I am a native Finnish speaker, but it took two additional Finns and a niche online dictionary for me to determine that Loviatar and her mother had swiftly heated the sauna and oiled its door with beer in preparation for her birthing. The words for “door” and “swiftly” are unrecognizable—though the verse’s two words for beer have survived the ravages of time intact. But even with its linguistic barriers slowing readers down, the Kalevala includes all the essentials of a punchy Nordic saga: heroes, villains, natural beauty, punishing weather, blondes. And also saunas.

Colonized by Sweden during the Northern Crusades of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, then ceded to Russia in 1809, the land populated by Finns did not achieve independence as its own country until 1917. But in the bisecting shadows of their powerful neighbors, Finns have always had their own stories, shared in a beast of a language further mangled by isolated dialects. While the Swedes had their castles, the Russians their palaces, and both powers had their empires, the comparatively modest Finns always had their saunas.

Given this history, you’d be hard-pressed to overstate the cultural significance of the sauna to its people. Sauna is the only Finnish word to make it into other languages; it is said that modern-day Finland has one sauna for every two Finns. People install them in the basements of apartment buildings, in the nooks of mid-sized bathrooms, in Olympic villages, in embassies. Only recently has the sauna ceased to operate in Finnish culture as the epic nexus of life and death: where babies of even the nonfolkloric variety were born (albeit at milder temperatures than their mythical counterparts), where bodies were prepared for burial—and where the country’s hard-won independence and identity was negotiated and preserved.

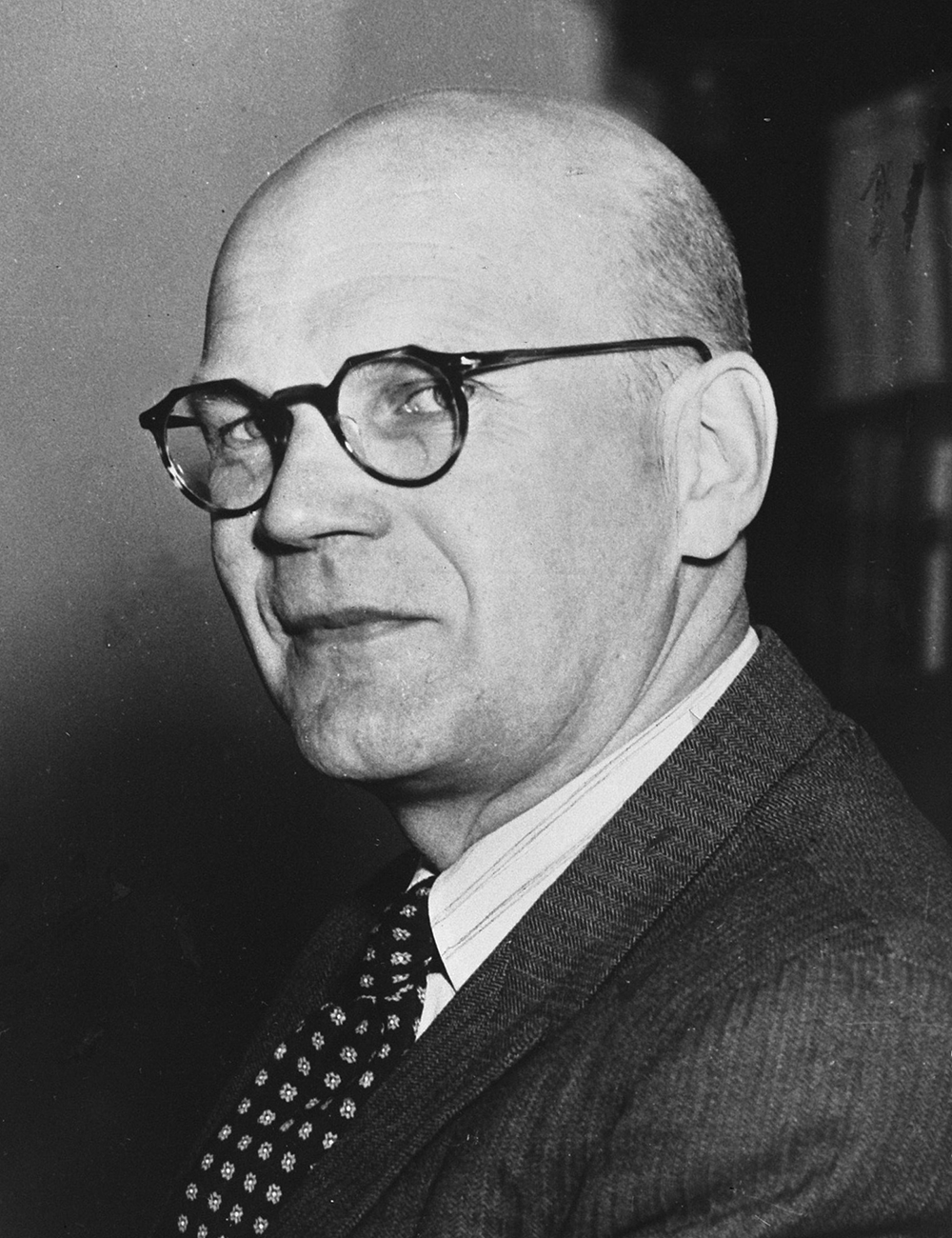

Although Lönnrot published the Kalevala in part to help shape Finnish national identity, even he could not have foreseen the extent to which politics would eventually imitate poetry. This was never more true than with Urho Kekkonen, a prime minister who became the country’s president in 1956, at a time when the independence and identity of Finland—bookended on its eastern edge by 833 miles’ worth of the Iron Curtain—were constantly threatened. The citizenry, intimidated by the ongoing Cold War, was ready for another hero.

Charismatic and unusually confident by demure Finnish standards, Kekkonen stepped into the role, casting himself as a new Väinämöinen, savior to a generation of tenuously independent and increasingly urban Finns. He would remain in power for nearly four momentous decades, but he solidified his mythological status by managing somehow to leave behind barely a shred of publicly available evidence to mark his personal life during his long tenure. We know, for instance, that Kekkonen died in 1986, four years after stepping down as president, but the cause of death remains uncertain and his medical records missing. What we have instead is obfuscation—that is, the legend.

So deftly did Kekkonen and his loyalists manage to bury the relevant records that, to this day, academics are still sifting through the archives in the hopes of painting an accurate portrait of Kekkonen’s Finland. Until 1995, the only person granted access to Kekkonen’s records was Juhani Suomi, a man with the unique status of being a member of Kekkonen’s devoted inner circle as well as a high-level bureaucrat at the Finnish foreign ministry. Suomi could be thought of as a modern-day, and more cynical, Lönnrot: for decades he documented Finland’s Cold War stories and legends with Kekkonen as their folk hero. He did so in deference to his friend’s sensibilities and legacy rather than to accuracy. Less biased historians have tried, with varying degrees of success, to piece together accurate details, but Suomi is the most cited Kekkonen historian around; his version—which takes an epic tone—was in textbooks long before anyone had a chance to challenge his accounts.

Even Kekkonen’s origin story maintains a mysterious mythological tinge: “born in a sauna” is something you hear a lot about him, though there is no evidence of it. But he claimed it happened, so the detail made it into his biography—all eight volumes authored by Suomi—and now is simply treated as fact. As with the Kalevala, tales of Kekkonen’s derring-do circulated through word of mouth long before the books came along. Each story expertly laces national pride with machismo along with an underlying theme of the president as an underdog simply trying not to get crushed under the weight of the Iron Curtain.

The Finnish border had taken some damage during the World War II, when Finland ceded the beloved city of Viipuri to the Soviets. City residents were forced to leave their homes just to continue to live in their country, and the loss became a painful national memory. Finnish independence always felt tenuous, as though someday one of our neighbors might rip the rug from under us, say just kidding, and take it back. Kekkonen’s public image provided an antidote to such uncertainty, bolstering an outsize national pride with larger-than-life Finnish romanticism.

And where else would a Finnish folk hero save the day, if not from a sauna? One of Kekkonen’s löylys, on the coast of Helsinki in the middle of the twentieth century, features heavily in stories about him. U.S. secretary of state Dean Rusk had made not taking a sauna with Kekkonen an essential part of his travel rider, only to have the Finnish premier drop his pants in front of him at the sauna door. Dared to embody the caricature of the uptight American, Rusk obliged by remaining suited up on a lounger in the adjoining room. For the duration of their meeting, the men yelled to each other through the sauna’s open door. And there’s the story of Nikita Khrushchev’s silk knickers, which he is said to have insisted on wearing into the sauna. According to lore, they were specifically pink, of course—taking the Russians down a peg.

In reality, Kekkonen’s governance tended toward the authoritarian. Part Lyndon Johnson–style parliamentary mastermind and bully, part aspiring despot, he took to dissolving parliament so often that governing was possible only when the proposed policies were to his liking. And though he was cast as a national symbol, his foreign policy took a more deferential tack. Poking the Russian bear had seldom worked in Finland’s favor, so Kekkonen made nice. In his decades at the helm of the country he worshipped, he crafted a foreign policy so deferential to Moscow that the term Finlandization was coined to describe a geopolitical lapdog.

In lieu of a functioning democracy and a free press, the home audience had to settle for tales of the virile, scrappy Finn going head-to-head with the most powerful nations in the world, exposing them as timid, dainty little things—too prudish to take their pants off, too prissy to cast aside their fine silk. Whether or not the stories were true did not matter. Either way, the Finns lived on.

In the Kalevala’s final rune, number fifty, Väinämöinen sets sail and leaves Kalevala behind. He vows to return when he is needed to defend the citizenry once more. But in the meantime, he leaves them the dual gifts of joy and songs. A chorus of singers switches from the third to the first person in the epilogue that follows: “I should shut my mouth already, tie my tongue.” They sing of how there is no one left to hear their song and how weary they have grown. They congratulate themselves for the road they have paved, the branches they have cleared for new poems, for a rising youth and for a growing people. The listener understands that it is not only Väinämöinen leaving but also those who sustained him. His farewell heralds the end of paganism in Finland and the beginning of Christendom’s reign.

Some thirty years after Kekkonen’s death, the oral history of the saga-hero president continues to be sung, in songs of pink knickers and sauna surveillance by Cold War bigwigs such as the CIA, MI6, and the KGB. But soon they, too, will depart. As Väinämöinen’s leaving marked a religious shift, so did Kekkonen’s exit signal a political one, heralding the end of monocracy and the beginning of a more genuine democracy. After he stepped down, the power of the presidency was aggressively curtailed. Today the post is largely ceremonial, with power residing in Parliament.

Finland’s independence is now just over a century old; the centennial was celebrated in 2017. Kekkonen’s ghost looms heavy over a new national identity, one that is at odds with the level of acquiescence and secrecy involved in forging contemporary Finland. Though the ability to work with a tempestuous neighbor remains a hallmark of its foreign policy, Finland regularly finds itself in the upper echelons of transparency and democracy indexes. Perhaps that is why so many prefer to look away from Kekkonen’s autocratic bent and focus instead on just how profoundly kitsch he was. Photos of him sporting his signature thick black-rimmed glasses have become a kind of hipster flourish of choice for many Helsinki establishments. He the proud father of a nation, we his loving but somewhat embarrassed progeny.

Current and future generations of Finns are not afforded the option of separating historical facts from fiction. Though in time historians will no doubt uncover new details of the country’s Cold War politics, for the most part myths will have to suffice. But with nationalism on the rise across the West, including in Finland, stories with the power to help a poor, largely rural ethnic community sustain and climb its way out from under regional giants are proving irresistible to today’s ethnocentric nationalists. These nationalists would have us believe that countries are defined by their borders and incapable of surviving the addition of new voices to our choruses. So as new generations of Finns sit in charred wooden rooms, throwing water onto scalding rocks, perhaps someone will compose a song about how to separate the lies of nationalism from the gifts of independence.