The newsmonger is one who always has ready gossip from some unheard-of soldier, or a slave belonging to one Asteus, a piper, or Lycon, an obscure contractor, just back from the battlefield. The authorities for his reports are of the sort that you can never get hold of.

If anybody asks, “Do you believe this?” he replies, “Why, the story is noised all about the city, constantly gaining ground, and the whole population is of one mind. Everybody is agreed about the battle. It must have been a regular death’s feast.” He reads a proof of it, too, in the faces of men in authority, for they all wear a changed look. He says he overheard that a man had come from Macedonia who knows the whole history of the battle, and that he has been concealed now five days in a house with the authorities. There is a convincing pathos in his voice—you can imagine it!—as he tells his story and exclaims: “Luckless Cassander! Ill-starred hero! Lo! the fickleness of fortune! Vain it was that he rose to power. But what I say is strictly between ourselves.” Then he trips off and repeats the story to every man in town.

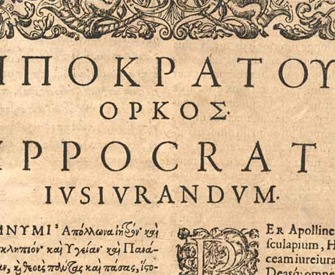

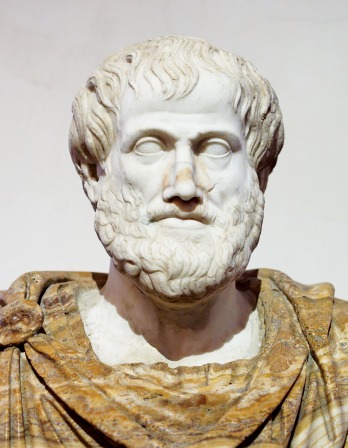

From his Characters. A student of the Lyceum, the Athenian academy founded by Aristotle, Theophrastus succeeded his teacher as head of the school when Aristotle retired in 323 bc. Around four years later, Theophrastus wrote this work, whose thirty archetypes represent various forms of moral behavior. At the end of his life, when asked by his students if he had any parting words, Theophrastus said, “Just this: that many of the pleasures life boasts are illusory. For just as we begin to live, we die. Hence nothing is more unprofitable than love of glory.”

Back to Issue