As peace is of all goodness, so war is an emblem, a hieroglyphic, of all misery.

—John Donne, 1622Louis-Ferdinand Céline Bids Farewell to His Colonel

Losing one’s virginity to the horrors of war.

You can be a virgin in horror the same as in sex. How, when I left the Place Clichy, could I have imagined such horror? Who could have suspected, before getting really into the war, all the ingredients that go to make up the rotten, heroic, good-for-nothing soul of man? And there I was, caught up in a mass flight into collective murder, into the fiery furnace…. Something had come up from the depths, and this is what happened.

The colonel was still as cool as a cucumber. I watched him as he stood on the embankment, taking little messages sent by the general, reading them without haste as the bullets flew all around him, and tearing them into little pieces. Did none of those messages include an order to put an immediate stop to this abomination? Did no top brass tell him there had been a misunderstanding? A horrible mistake? A misdeal? That somebody’d got it all wrong, that the plan had been for maneuvers, a sham battle, not a massacre! Not at all! “Keep it up, colonel! You’re doing fine!” That’s what General des Entrayes, the head of our division and commander over us all, must have written in those notes that were being brought every five minutes by a courier who looked greener and more shitless each time. I could have palled up with that boy, we’d have been scared together. But we had no time to fraternize.

So there was no mistake? So there was no law against people shooting at people they couldn’t even see! It was one of the things you could do without anybody reading you the riot act. In fact, it was recognized and probably encouraged by upstanding citizens, like the draft, or marriage, or hunting!… No two ways about it. I was suddenly on the most intimate terms with war. I’d lost my virginity. You’ve got to be pretty much alone with her as I was then to get a good look at her, the slut, full face and profile. A war had been switched on between us and the other side, and now it was burning! Like the current between the two carbons of an arc lamp! And this lamp was in no hurry to go out! It would get us all, the colonel and everyone else; he looked pretty spiffy now, but he wouldn’t roast up any bigger than me when the current from the other side got him between the shoulders.

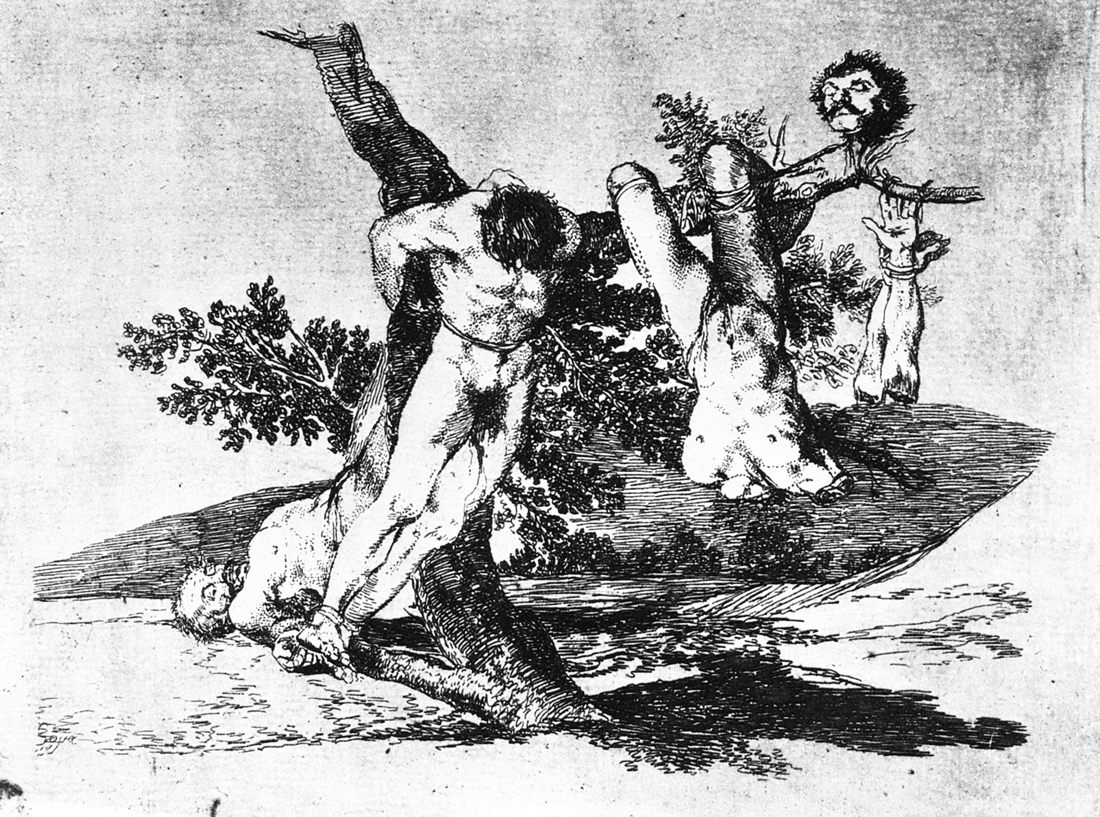

Heroic Feat! Against the Dead!, from The Disasters of War, by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, 1814. Prado Museum, Madrid.

There are different ways of being condemned to death. Oh! What wouldn’t I have given to be in jail instead of here! What a fool I’d been! If only I had had a little foresight and stolen something or other when it would have been so easy and there was still time. I never think of anything. You come out of jail alive, out of a war you don’t! The rest is blarney.

If only I’d had time, but I didn’t. There was nothing left to steal. How pleasant it would be in a cozy little jailhouse, I said to myself, where the bullets couldn’t get in. Where they never got in! I knew of one that was ready and waiting, all sunny and warm! I saw it in my dreams, the jailhouse of Saint-Germain to be exact, right near the forest. I knew it well, I’d often passed that way. How a man changes! I was a child in those days, and that jail frightened me. Because I didn’t know what men are like. Never again will I believe what they say or what they think. Men are the thing to be afraid of, always, men and nothing else.

How much longer would this madness have to go on before these monsters dropped with exhaustion? How long could a convulsion like this last? Months? Years? How many? Maybe till everyone’s dead? All these lunatics? Every last one of them? And seeing that events were taking such a desperate turn, I decided to stake everything on one throw, to make one last try, to see if I couldn’t stop the war, just me, all by myself! At least in this one spot where I happened to be.

The colonel was only two steps away from me, pacing. I’d talk to him. Something I’d never done. This was a time for daring. The way things stood, there was practically nothing to lose. “What is it?” he’d ask me, startled, I imagined, at my bold interruption. Then I’d explain the situation as I saw it, and we’d see what he thought. The essential is to talk things over. Two heads are better than one.

I was about to take the decisive step when, at that very moment, who should arrive at the double but a dismounted cavalryman (as we said in those days), exhausted, shaky in the joints, holding his helmet upside-down in one hand like Belisarius, trembling, all covered with mud, his face even greener than the courier I mentioned before. He stammered and gulped. You’d have thought he was struggling to climb out of a tomb, and it had made him sick to his stomach. Could it be that this spook didn’t like bullets any more than I did? That he saw them coming like me?

“What is it?” Disturbed, the colonel stopped him short; the glance he flung at that ghost was of steel.

It made our colonel very angry to see that wretched cavalryman so incorrectly clad and shitting in his pants with fright. The colonel had no use for fear, that was a sure thing. And especially that helmet held in hand like a bowler was really too much in a combat regiment like ours that was just getting into the war. It was as if this dismounted cavalryman had seen the war and taken his hat off in greeting.

Under the colonel’s withering look the wobbly messenger snapped to attention, pressing his little finger to the seam of his trousers as the occasion demanded. And so he stood on the embankment, stiff as a board, swaying, the sweat running down his chinstrap; his jaws were trembling so hard that little abortive cries kept coming out of him, like a puppy dreaming. You couldn’t make out whether he wanted to speak to us or whether he was crying.

Our Germans squatting at the end of the road had just changed instruments. Now they were having their fun with a machine-gun, sputtering like handfuls of matches, and all around us flew swarms of angry bullets, as hostile as wasps.

The man finally managed to articulate a few words:

“Colonel, sir, Sergeant Barousse has been killed.”

“So what?”

“He was on his way to meet the bread wagon on the Etrapes road, sir.”

“So what?”

“He was blown up by a shell!”

“So what, dammit!”

“That’s what, colonel, sir.”

“Is that all?”

“Yes, sir, that’s all, colonel, sir.”

“What about the bread?” the colonel asked.

That was the end of the dialogue, because, I remember distinctly, he barely had time to say, “What about the bread?” That was all. After that there was nothing but flame and noise. The kind of noise you wouldn’t have thought possible. Our eyes, ears, nose, and mouth were so full of that noise I thought it was all over and I’d turned into noise and flame myself.

After a while, the flame went away, the noise stayed in my head, and my arms and legs trembled as if somebody were shaking me from behind. My limbs seemed to be leaving me, but then in the end they stayed on. The smoke stung my eyes for a long time, and the prickly smell of powder and sulfur hung on, strong enough to kill all the fleas and bedbugs in the whole world.

I thought of Sergeant Barousse, who had just gone up in smoke like the man told us. That was good news. Great, I thought to myself. That makes one less stinker in the regiment! He wanted to have me court-martialed for a can of meat. “It’s an ill wind,” I said to myself. In that respect, you can’t deny it, the war seemed to serve a purpose now and then! I knew of three or four more in the regiment, real scum, that I’d have gladly helped to make the acquaintance of a shell, like Barousse.

As for the colonel, I didn’t wish him any hard luck. But he was dead too. At first I didn’t see him. The blast had carried him up the embankment and laid him down on his side, right in the arms of the dismounted cavalryman, the courier, who was finished too. They were embracing each other for the moment and for all eternity, but the cavalryman’s head was gone, all he had was an opening at the top of the neck, with blood in it bubbling and glugging like jam in a kettle. The colonel’s belly was wide open and he was making a nasty face about it. It must have hurt when it happened. Tough shit for him! If he’d beat it when the shooting started, it wouldn’t have happened.

All that tangled meat was bleeding profusely.

Shells were still bursting to the right and left of the scene.

I’d had enough. I was glad to have such a good pretext for making myself scarce. I even hummed a tune and reeled like when you’ve been rowing a long way and your legs are wobbly. “Just one shell!” I said to myself. “Amazing how quick just one shell can clean things up. Could you believe it?” I kept saying to myself. “Could you believe it!”

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

From Journey to the End of Night, a semi-autobiographical novel drawn from the author’s experiences as a soldier in the French cavalry during World War I.