The retail butchers of New York City, as a class, are made the objects of sweeping accusations of dishonesty toward customers in the annual report of Patrick Derry, chief of the city bureau of weights and measures, submitted last week to Mayor McClellan.

Mr. Derry does not make much distinction, and his language would lead the uninformed outsider to believe that New York retailers as a class were of the sort he describes. With several thousand shops in operation in the city, a certain small percentage of which are of the fly-by-night order—now here and the next month gone out of business—it is inevitable that there should be more or less business irresponsibility. But that butchers as a class do the things Derry accuses them of will be generally and indignantly denied. Here are some extracts from his report:

Butchers in the retail trade as a rule use spring scales, most of which present to the view of the purchaser a dial upon which a moving hand indicates the weight of the object being sold. By removing the glass front and loosening a little screw, adjusting the hand a trifle, tightening the screw again and replacing the glass front, the butcher may rob hundreds of people out of an ounce or more in every pound of meat he is paid for.

Some spring scales do not require this labor to enable the butcher to steal his customers’ money. The scale manufacturer provides at the side or back or top of the scale, a little adjusting thumbscrew, which by a touch sets the scale against the customer.

Some butchers have their scales set properly and conforming, when empty, to the standards, but each day when commencing business a strip of fat or a slice or two of bacon is attached to the underside of the pan of the scale.

Some butchers with neat-looking places have a sheet of paper on the scale and under it a dozen or so ten-penny nails or a couple of S-hooks innocently hanging from the slide, or upon the hook properly belonging to the scale hangs a pad of memorandum sheets or “tickets,” any of which devices serve to rob the customer.

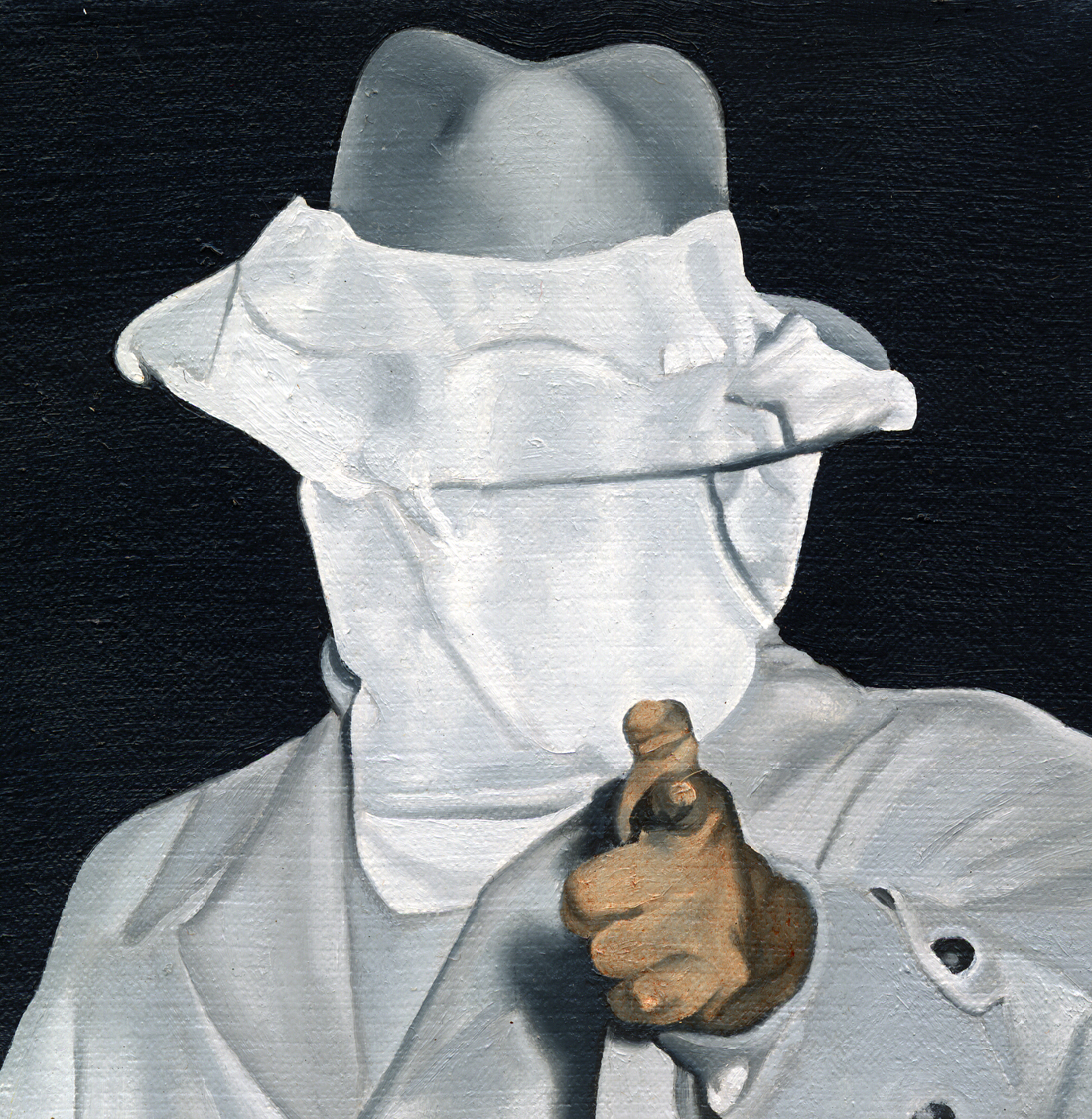

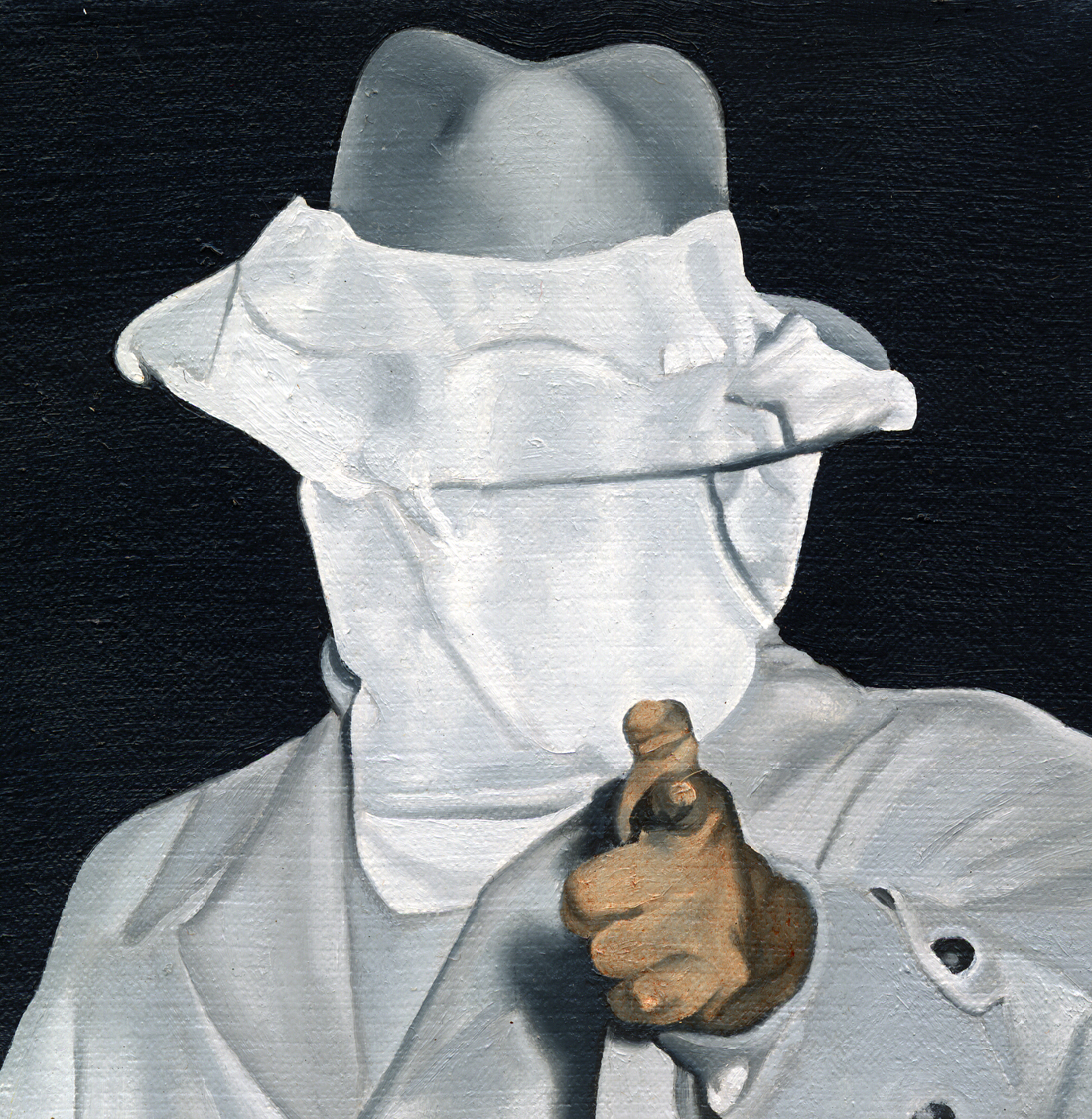

Worst Case Scenario (VII), by Dotty Attie, 2013. © Dotty Attie, courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

Any of these different tricks would be apparent to an observant customer, but apparently people do not seem to notice that the hand on the scale does not stand at nor start from the zero mark, but from one ounce or two, three, four, five or more ounces past the zero; they only notice that the hands point to the two pounds or so they want to get.

Some butchers have been reported as requiring their bench men to make their wages in short-weighing the customers. This they do by means of well-lubricated slides on the spring scales that keep the pan jumping quickly up and down when meat is dropped upon it, and catching the weight at the lowest drop of the pan, quickly take off the meat, announce the false weight to the customer, write out a memorandum ticket and pass meat and ticket to proprietor or foreman, who weighs the meat upon a scale not subject to customers’ scrutiny, and credits the bench man with the amount he has defrauded the customer of. If some customer does make a protest, a quick and abject expression of sorrow at the “mistake” and the adjustment of the cash rectifies the error and prosecution rarely, if ever, follows.

From the Official Journal of Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America. Patrick Derry’s full report was published in Good Housekeeping under the title “Dishonest Grocers and Butchers.” After cataloging the various tricks of the trade used to deceive consumers, Derry concluded with the conciliatory observation, “Of honest grocers and butchers there are many: but know your dealer.” Four years later, in 1910, Derry resigned his post after an investigation revealed that, among other infractions, 309 scales, 109 weights, and 128 measures in Manhattan shops were inaccurate.

Back to Issue