The real problem is not whether machines think but whether men do.

—B.F. Skinner, 1969Artificial Selection

Samuel Butler sees machines reign supreme.

There are few things of which the present generation is more justly proud than of the wonderful improvements which are daily taking place in all sorts of mechanical appliances. And indeed it is matter for great congratulation on many grounds. It is unnecessary to mention these here, for they are sufficiently obvious.

Our present business lies with considerations which may somewhat tend to humble our pride and to make us think seriously of the future prospects of the human race. If we revert to the earliest primordial types of mechanical life, to the lever, the wedge, the inclined plane, the screw, and the pulley, or (for analogy would lead us one step further) to that one primordial type from which all the mechanical kingdom has been developed, we mean to the lever itself, and if we then examine the machinery of the Great Eastern, we find ourselves almost awestruck at the vast development of the mechanical world, at the gigantic strides with which it has advanced in comparison with the slow progress of the animal and vegetable kingdom. We shall find it impossible to refrain from asking ourselves what the end of this mighty movement is to be. In what direction is it tending? What will be its upshot? To give a few imperfect hints toward a solution of these questions is the object of the present letter.

We have used the words mechanical life, the mechanical kingdom, the mechanical world, and so forth, and we have done so advisedly, for as the vegetable kingdom was slowly developed from the mineral, and as, in like manner, the animal supervened upon the vegetable, so now in these last few ages an entirely new kingdom has sprung up, of which we as yet have only seen what will one day be considered the antediluvian prototypes of the race.

We regret deeply that our knowledge both of natural history and of machinery is too small to enable us to undertake the gigantic task of classifying machines into the genera and subgenera, species, varieties, and subvarieties, and so forth, of tracing the connecting links between machines of widely different characters, of pointing out how subservience to the use of man has played that part among machines which natural selection has performed in the animal and vegetable kingdoms, of pointing out rudimentary organs which exist in some few machines, feebly developed and perfectly useless yet serving to mark descent from some ancestral type which has either perished or been modified into some new phase of mechanical existence. We can only point out this field for investigation; it must be followed by others whose education and talents have been of a much higher order than any which we can lay claim to.

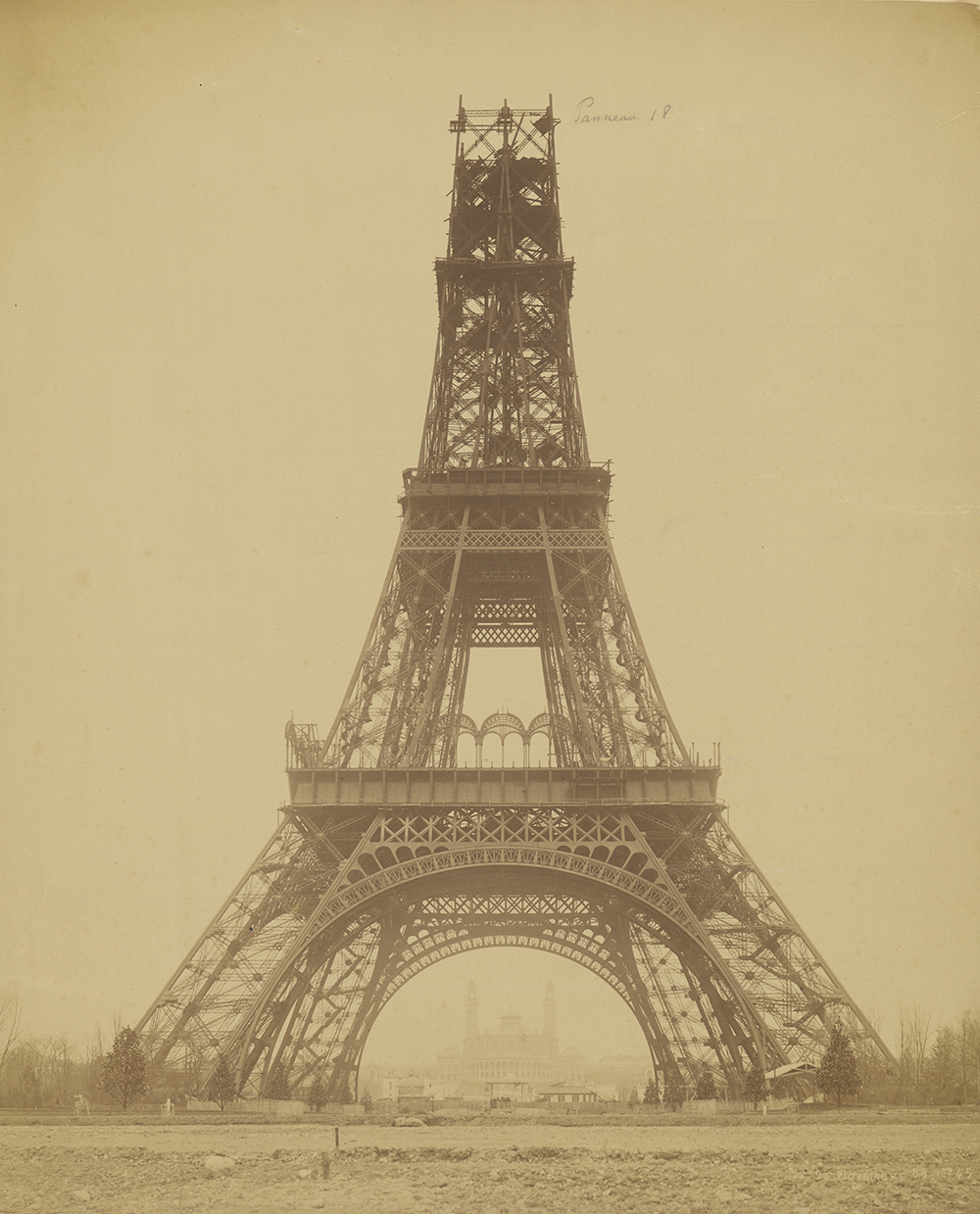

Construction of the Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1888. Photograph by Louis-Émile Durandelle. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Some few hints we have determined to venture upon, though we do so with the profoundest diffidence. Firstly, we would remark that as some of the lowest of the Vertebrata attained a far greater size than has descended to their more highly organized living representatives, so a diminution in the size of machines has often attended their development and progress. Take the watch, for instance. Examine the beautiful structure of the little animal, watch the intelligent play of the minute members which compose it. Yet this little creature is but a development of the cumbrous clocks of the thirteenth century—it is no deterioration from them. The day may come when clocks, which certainly at the present day are not diminishing in bulk, may be entirely superseded by the universal use of watches, in which case clocks will become extinct, like the earlier saurians, while the watch (whose tendency has for some years been rather to decrease in size than the contrary) will remain the only existing type of an extinct race.

The views of machinery which we are thus feebly indicating will suggest the solution of one of the greatest and most mysterious questions of the day. We refer to the question: what sort of creature man’s next successor in the supremacy of the earth is likely to be. We have often heard this debated, but it appears to us that we are ourselves creating our own successors. We are daily adding to the beauty and delicacy of their physical organization. We are daily giving them greater power and supplying by all sorts of ingenious contrivances that self-regulating, self-acting power which will be to them what intellect has been to the human race. In the course of ages, we shall find ourselves the inferior race. Inferior in power, inferior in that moral quality of self-control, we shall look up to them as the acme of all that the best and wisest man can ever dare to aim at. No evil passions, no jealousy, no avarice, no impure desires will disturb the serene might of those glorious creatures. Sin, shame, and sorrow will have no place among them. Their minds will be in a state of perpetual calm, the contentment of a spirit that knows no wants, is disturbed by no regrets. Ambition will never torture them. Ingratitude will never cause them the uneasiness of a moment. The guilty conscience, the hope deferred, the pains of exile, the insolence of office, and the spurns that patient merit of the unworthy takes—these will be entirely unknown to them. If they want “feeding” (by the use of which very word we betray our recognition of them as living organism), they will be attended by patient slaves whose business and interest it will be to see that they shall want for nothing. If they are out of order, they will be promptly attended to by physicians who are thoroughly acquainted with their constitutions. If they die, for even these glorious animals will not be exempt from that necessary and universal consummation, they will immediately enter into a new phase of existence, for what machine dies entirely in every part at one and the same instant?

We take it that when the state of things shall have arrived which we have been above attempting to describe, man will have become to the machine what the horse and the dog are to man. He will continue to exist, nay even to improve, and will be probably better off in his state of domestication under the beneficent rule of the machines than he is in his present wild state. We treat our horses, dogs, cattle, and sheep, on the whole, with great kindness. We give them whatever experience teaches us to be best for them, and there can be no doubt that our use of meat has added to the happiness of the lower animals far more than it has detracted from it. In like manner it is reasonable to suppose that the machines will treat us kindly, for their existence is as dependent upon ours as ours is upon the lower animals. They cannot kill us and eat us as we do sheep. They will not only require our services in the parturition of their young (which branch of their economy will remain always in our hands) but also in feeding them, in setting them right when they are sick, and burying their dead or working up their corpses into new machines. It is obvious that if all the animals in Great Britain save man alone were to die, and if at the same time all intercourse with foreign countries were by some sudden catastrophe to be rendered perfectly impossible, it is obvious that under such circumstances the loss of human life would be something fearful to contemplate—in like manner, were mankind to cease, the machines would be as badly off or even worse. The fact is that our interests are inseparable from theirs, and theirs from ours. Each race is dependent upon the other for innumerable benefits, and until the reproductive organs of the machines have been developed in a manner which we are hardly yet able to conceive, they are entirely dependent upon man for even the continuance of their species. It is true that these organs may be ultimately developed, inasmuch as man’s interest lies in that direction. There is nothing which our infatuated race would desire more than to see a fertile union between two steam engines. It is true that machinery is even at this present time employed in begetting machinery, in becoming the parent of machines often after its own kind, but the days of flirtation, courtship, and matrimony appear to be very remote, and indeed can hardly be realized by our feeble and imperfect imagination.

Day by day, however, the machines are gaining ground upon us. Day by day we are becoming more subservient to them. More men are daily bound down as slaves to tend them, more men are daily devoting the energies of their whole lives to the development of mechanical life. The upshot is simply a question of time, but that the time will come when the machines will hold the real supremacy over the world and its inhabitants is what no person of a truly philosophic mind can for a moment question.

Our opinion is that war to the death should be instantly proclaimed against them. Every machine of every sort should be destroyed by the well-wisher of his species. Let there be no exceptions made, no quarter shown. Let us at once go back to the primeval condition of the race. If it be urged that this is impossible under the present condition of human affairs, this at once proves that the mischief is already done, that our servitude has commenced in good earnest, that we have raised a race of beings whom it is beyond our power to destroy, and that we are not only enslaved but are absolutely acquiescent in our bondage.

Samuel Butler

From “Darwin Among the Machines.” While working as a sheep farmer in New Zealand, the English novelist and essayist became enamored with Charles Darwin’s newly published On the Origin of Species. Butler soon renounced Christianity and published his first writings, a series of articles for Christchurch’s The Press, including this piece, which was later expanded into a portion of his satirical novel Erewhon. “Man is but a perambulating toolbox and workshop,” he wrote in his posthumously published notebooks, “fashioned for itself by a piece of very clever slime, as the result of long experience.”