Of all the creatures that breathe and creep on the surface of the earth, none is more to be pitied than man.

—Homer, 750 BCNatural Selection

Willa Cather throws a bride to the wolves.

When Pavel and Peter were young men living at home in Russia, they were asked to be groomsmen for a friend who was to marry the belle of another village. It was in the dead of winter, and the groom’s party went over to the wedding in sledges. Peter and Pavel drove in the groom’s sledge, and six sledges followed with all his relatives and friends.

After the ceremony at the church, the party went to a dinner given by the parents of the bride. The dinner lasted all afternoon; then it became a supper and continued far into the night. There was much dancing and drinking. At midnight the parents of the bride said goodbye to her and blessed her. The groom took her up in his arms and carried her out to his sledge and tucked her under the blankets. He sprang in beside her, and Pavel and Peter took the front seat. Pavel drove. The party set out with singing and the jingle of sleigh bells, the groom’s sledge going first. All the drivers were more or less the worse for merrymaking, and the groom was absorbed in his bride.

The wolves were bad that winter, and everyone knew it, yet when they heard the first wolf cry, the drivers were not much alarmed. They had too much good food and drink inside them. The first howls were taken up and echoed with quickening repetitions. The wolves were coming together. There was no moon, but the starlight was clear on the snow. A black drove came up over the hill behind the wedding party. The wolves ran like streaks of shadow; they looked no bigger than dogs, but there were hundreds of them.

Something happened to the hindmost sledge: the driver lost control—he was probably very drunk—the horses left the road, the sledge was caught in a clump of trees, and overturned. The occupants rolled out over the snow, and the fleetest of the wolves sprang upon them. The shrieks that followed made everybody sober. The drivers stood up and lashed their horses. The groom had the best team and his sledge was lightest—all the others carried from six to a dozen people.

Another driver lost control. The screams of the horses were more terrible to hear than the cries of the men and women. Nothing seemed to check the wolves. It was hard to tell what was happening in the rear; the people who were falling behind shrieked as piteously as those who were already lost. The little bride hid her face on the groom’s shoulder and sobbed. Pavel sat still and watched his horses. The road was clear and white, and the groom’s three blacks went like the wind. It was only necessary to be calm and to guide them carefully.

At length, as they breasted a long hill, Peter rose cautiously and looked back. “There are only three sledges left,” he whispered.

“And the wolves?” Pavel asked.

“Enough! Enough for all of us.”

Pavel reached the brow of the hill, but only two sledges followed him down the other side. In that moment on the hilltop, they saw behind them a whirling black group on the snow. Presently the groom screamed. He saw his father’s sledge overturned, with his mother and sisters. He sprang up as if he meant to jump, but the girl shrieked and held him back. It was even then too late. The black ground shadows were already crowding over the heap in the road, and one horse ran out across the fields, his harness hanging to him, wolves at his heels. But the groom’s movement had given Pavel an idea.

They were within a few miles of their village now. The only sledge left out of the six was not very far behind them, and Pavel’s middle horse was failing. Beside a frozen pond something happened to the other sledge; Peter saw it plainly. Three big wolves got abreast of the horses, and the horses went crazy. They tried to jump over each other, got tangled up in the harness, and overturned the sledge.

When the shrieking behind them died away, Pavel realized that he was alone upon the familiar road. “They still come?” he asked Peter.

“Yes.

“How many?”

“Twenty, thirty—enough.”

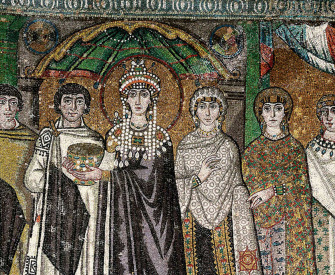

Royal coat of arms of King William III and Queen Mary II of England, c. 1690. © Joanna Booth, The Bridgeman Art Library.

Now his middle horse was being almost dragged by the other two. Pavel gave Peter the reins and stepped carefully into the back of the sledge. He called to the groom that they must lighten—and pointed to the bride. The young man cursed him and held her tighter. Pavel tried to drag her away. In the struggle, the groom rose. Pavel knocked him over the side of the sledge and threw the girl after him. He said he never remembered exactly how he did it, or what happened afterward. Peter, crouching in the front seat, saw nothing. The first thing either of them noticed was a new sound that broke into the clear air, louder than they had ever heard it before—the bell of the monastery of their own village, ringing for early prayers.

Pavel and Peter drove into the village alone, and they had been alone ever since. They were run out of their village. Pavel’s own mother would not look at him. They went away to strange towns, but when people learned where they came from, they were always asked if they knew the two men who had fed the bride to the wolves. Wherever they went, the story followed them.

Willa Cather

From My Ántonia. Born in Virginia in 1873, Cather at the age of nine moved with her family to Nebraska, where she lived among immigrants settling the Great Plains. She graduated from the state’s university in 1895 and became the managing editor of McClure’s Magazine in New York City in 1905, serving until 1912. Cather published O Pioneers!, her second novel, in 1913. She later remarked that “all my stories have been written with material that was gathered—no, God save us! not gathered but absorbed—before I was fifteen years old.”