My dear L,

I scarcely consider myself to have seen anything of art in England. The calls of the living world were so various and demanding, that I had so little leisure for reflection, and although I saw many paintings, I could not study them—and many times I saw them in a state of the nervous system too jaded and depressed to receive the full force of the impression. A day or two before I left, I visited the National Gallery, and made a rapid survey of its contents. There were two of Turner’s masterpieces there, which he presented on the significant condition that they should hang side by side with their two finest Claudes. I thought them all four fine pictures, but I liked the Turners best. Yet I did not think any of them fine enough to form an absolute limit to human improvement. But, till I had been in Paris a day or two, perfectly secluded, at full liberty to think and rest, I did not feel that my time for examining art had really come.

It was then with a thrill almost of awe that I approached the Louvre. Here, perhaps, I said to myself, I shall answer fully the question that has long wrought within my soul: what is art, and what can it do? Here, perhaps, these yearnings for the ideal will meet their satisfaction. The ascent to the picture gallery tends to produce a flutter of excitement and expectation. Magnificent staircases, dim perspectives of frescoes and carvings, the glorious hall of Apollo, rooms with mosaic pavements, antique vases, countless spoils of art, dazzle the eye of the neophyte and prepare the mind for some grand enchantment.

I first walked through the whole, offering my mind up aimlessly to see if there were any picture there great and glorious enough to seize and control my whole being, and answer at once the cravings of the poetic and artistic element. For any such I looked in vain. I saw a thousand beauties, as also a thousand enormities, but nothing of that overwhelming, subduing nature which I had conceived. Most of the men there had painted with dry eyes and cool hearts, thinking only of the mixing of their colors and the jugglery of their art, thinking little of heroism, faith, love, or immortality. Yet when I had resigned this longing, then I began to enjoy very heartily what there was.

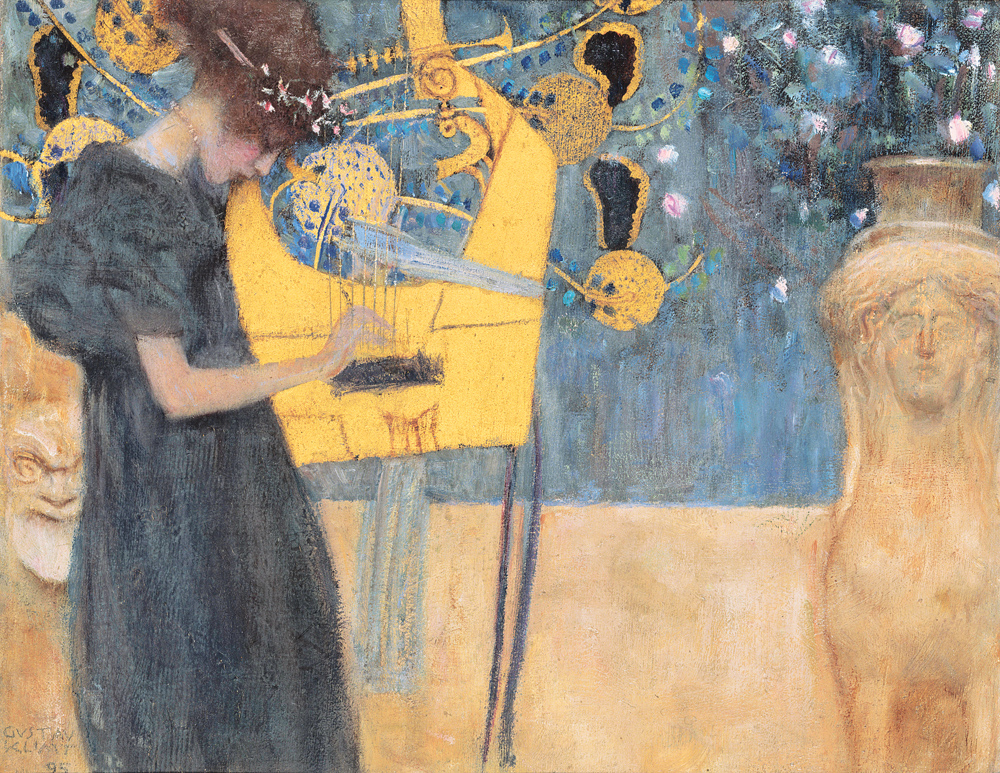

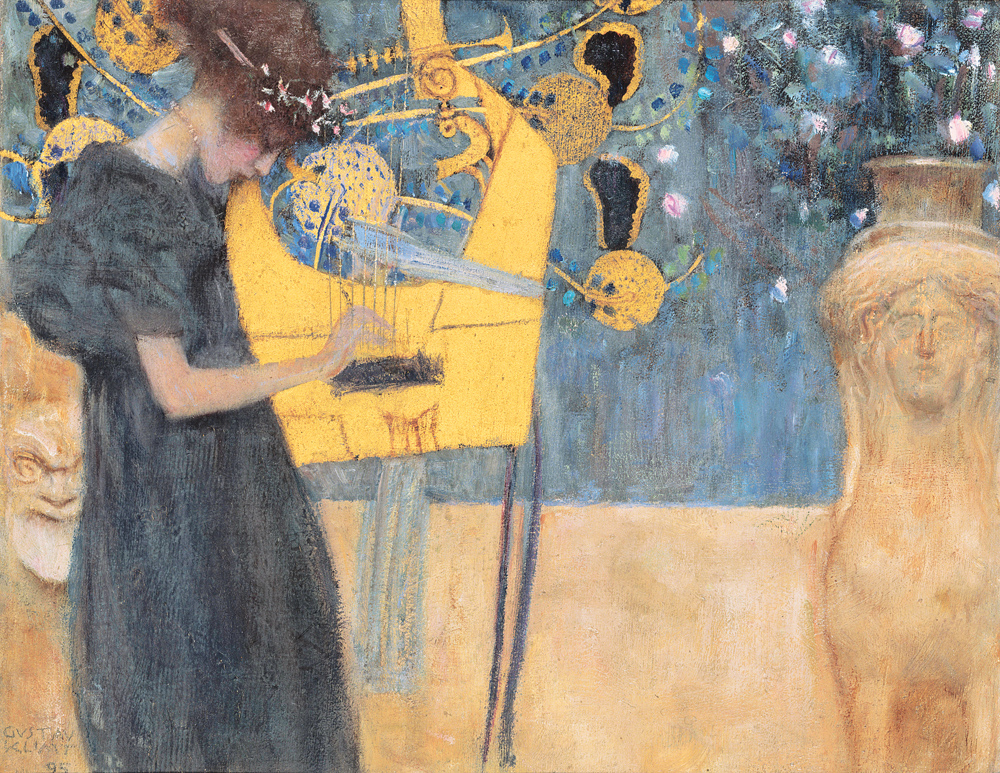

Music (I), by Gustav Klimt, 1895. Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany.

One of my favorites was Rembrandt. I always did admire the gorgeous and solemn mysteries of his coloring. Rembrandt is like Hawthorne. He chooses simple and everyday objects and so arranges light and shadow as to give them a somber richness and a mysterious gloom. The House of Seven Gables is a succession of Rembrandt pictures, done in words instead of oils. Now this pleases us because our life really is a haunted one; the simplest thing in it is a mystery, the invisible world always lies round us like a shadow, and therefore this dreamy golden gleam of Rembrandt meets somewhat in our inner consciousness to which it corresponds. There were no pictures in the gallery which I looked upon so long, and to which I returned so often and with such growing pleasure, as these. There were Raphaels there, which still disappointed me, because from Raphael I asked and expected more. I wished to feel his hand on my soul with a stronger grasp.

But Rubens, the great, joyous, full-souled, all-powerful Rubens! There he was, full as ever of triumphant, abounding life—disgusting and pleasing, making me laugh and making me angry, defying me to dislike him, dragging me at his chariot wheels, in spite of my protests forcing me to confess that there was no other but he.

I should compare Rubens to Shakespeare, for the wonderful variety and vital force of his artistic power. Like Shakespeare, he forces you to accept and to forgive a thousand excesses and uses his own faults as musicians use discords, only to enhance the perfection of harmony. There certainly is some use even in defects. A faultless style sends you to sleep. Defects rouse and excite the sensibility to seek and appreciate excellences. Some of Shakespeare’s finest passages explode all grammar and rhetoric like skyrockets.

From Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands. Traveling to Europe at the age of forty-one, in part to escape the uproar caused by Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, Stowe kept a detailed journal that included travel etiquette for Americans, urging them not to graffiti Shakespeare’s home. She befriended Lord Byron’s widow, who revealed her late husband’s adultery with his half sister, the story later told by Stowe in Lady Byron Vindicated.

Back to Issue