Don’t begin your poem the way the old

Cyclic “Homeric” poets saw fit to do it:

“I sing of the famous war and Priam’s fate.”

What’s to come out of the mouth of such a boaster?

The mountain labored and brought forth a mouse.

Ridiculous. He does much better who doesn’t

Try so hard or make such grandiose claims:

“Muse, tell me about the man who, after Troy,

Witnessed the ways of men in other places.”

His aim is light from smoke, not smoke from fire,

To make the wonders he tells of—Scylla, Charybdis,

Antiphates, the Cyclops—shine more brightly.

To tell Diomedes’ story he doesn’t think

He has to start with the death of the hero’s uncle,

Or start, in telling about the Trojan War,

By telling us how Helen came out of an egg.

He goes right to the point and carries the reader

Into the midst of things, as if known already;

And if there’s material that he despairs of presenting

So as to shine for us, he leaves it out;

And he makes his whole poem one. What’s true, what’s invented,

Beginning, middle, and end, all fit together.

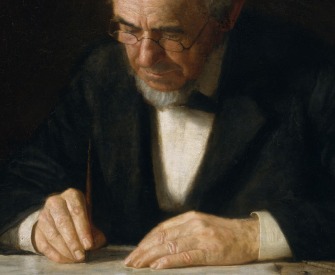

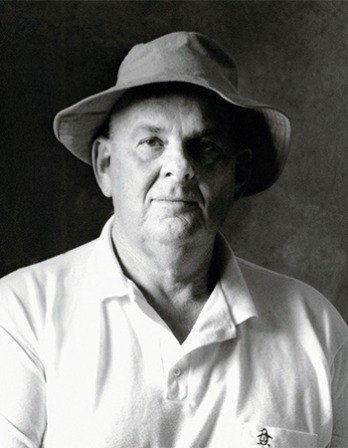

Translated by David Ferry. © 2001 by David Ferry. Used with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

From “Ars Poetica.” This instruction is from Book III of Horace’s Epistles; Book II includes a letter addressed to Emperor Augustus in which he bemoans the decline of literature. The poet studied for a time at the Academy in Athens, before joining the faction of Brutus during the civil wars beginning in 44 bc. In 39 bc he moved to Rome, realigned his politics, and soon published his Satires and Epodes.

Back to Issue