Art, like morality, consists of drawing the line somewhere.

—G.K. Chesterton, 1928Painting Little Bear

George Catlin’s portrait problems.

About four months previous to the moment I am now speaking of, I had passed up the Missouri river on the steamboat Yellow Stone, on which I ascended the Missouri to the mouth of Yellowstone river. While going up, this boat—having on board the United States Indian agent Major Sanford, Messrs. Pierre, Chouteau, and M’Kenzie of the American Fur Company, and myself as passengers—stopped at this trading post, and remained several weeks, where were assembled six hundred families of Sioux Indians, their tents being pitched in close order on an extensive prairie on the bank of the river.

This trading post, in charge of Mr. Laidlaw, is the concentrating place and principal trading depot for this powerful tribe, who number, when all taken together, something like forty or fifty thousand. On this occasion, five or six thousand had assembled to see the steamboat and meet the Indian agent, which and whom they knew were to arrive about this time. During the few weeks that we remained there, I was busily engaged painting my portraits, for here were assembled the principal chiefs and medicine men of the nation. To these people the operations of my brush were entirely new and unaccountable, and excited amongst them the greatest curiosity imaginable. Everything else (even the steamboat) was abandoned for the pleasure of crowding into my painting room and witnessing the result of each fellow’s success as he came out from under the operation of my brush.

They had been at first much afraid of the consequences that might flow from so strange and unaccountable an operation, but having been made to understand my views, they began to look upon it as a great honor and afforded me the opportunities that I desired, exhibiting the utmost degree of vanity for their appearance, both as to features and dress. The consequence was that my room was filled with the chiefs who sat around, arranged according to the rank or grade which they held in the estimation of their tribe, and in this order it became necessary for me to paint them, to the exclusion of those who never signalized themselves and were without any distinguishing character in society.

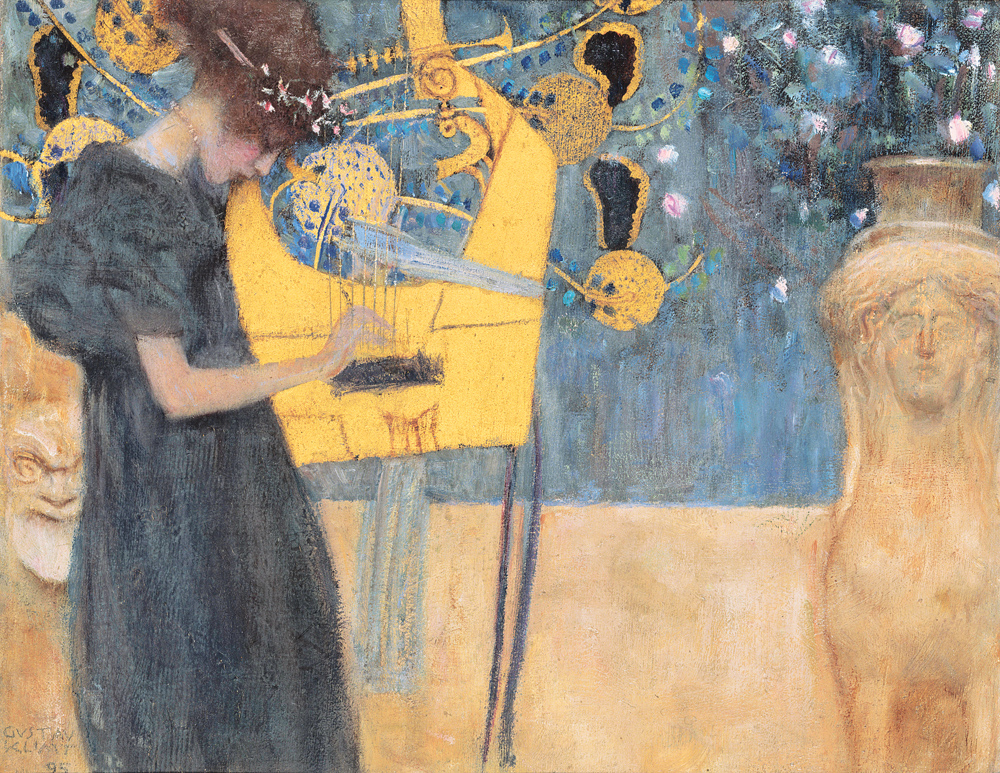

Music (I), by Gustav Klimt, 1895. Neue Pinakothek, Munich, Germany.

The first man on the list, was Hawangheeta (one horn), head chief of the nation, and after him the subordinate chiefs, or chiefs of bands, according to the estimation in which they were held by the chief and the tribe. My models were thus placed before me—whether ugly or beautiful, all the same—and I saw at once there was to be trouble somewhere, as I could not paint them all. The medicine men or high priests—who are esteemed by many of the oracles of the nation and the most important men in it—becoming jealous, commenced their harangues outside of the lodge, telling them that they were all fools—that those who were painted would soon die in consequence, and that these pictures, which had life to a considerable degree in them, would live in the hands of white men after they were dead and make them sleepless and endless trouble.

Those whom I had painted, though evidently somewhat alarmed, were unwilling to acknowledge it, and those whom I had not painted, unwilling to be outdone in courage, allowed me the privilege, braving and defying the danger that they were evidently more or less in dread of. Feuds began to arise, too, among some of the chiefs of the different bands, who (not unlike some instances among the chiefs and warriors of our own country), had looked upon their rival chiefs with unsleeping jealousy, until it had grown into disrespect and enmity. An instance of this kind presented itself at this critical juncture, in this assembly of inflammable spirits, which changed in a moment its features from the free and jocular garrulity of an Indian levee to the frightful yells and agitated treads and starts of an Indian battle! I had in progress at this time a portrait of Mahtotcheega (little bear) of the Oncpapa band, a noble fine fellow, who was sitting before me as I was painting. I was painting almost a profile view of his face, throwing a part of it into shadow, and had it nearly finished when an Indian by the name of Shonka (the dog), chief of the Cazazsheeta band, an ill-natured and surly man—despised by the chiefs of every other band—entered the wigwam in a sullen mood and seated himself on the floor in front of my sitter, where he could have a full view of the picture in its operation. After sitting awhile, he sneeringly spoke thus: “Mahtotcheega is but half a man.”

Dead silence ensued for a moment, and nought was in motion save the eyes of the chiefs, who were seated around the room, and darting their glances about upon each other in listless anxiety to hear the sequel that was to follow! During this interval, the eyes of Mahtotcheega had not moved—his lips became slightly curved, and he pleasantly asked in low and steady accent, “Who says that?” “Shonka says it,” was the reply; “and Shonka can prove it.” At this the eyes of Mahtotcheega, which had not yet moved, began steadily to turn—and slow, as if upon pivots—and when they were rolled out of their sockets till they had fixed upon the object of their contempt, his dark and jutting brows were shoving down in trembling contention with the blazing rays that were actually burning with contempt the object that was before them. “Why does Shonka say it?”

“Ask Wechashawakon (the painter), he can tell you; he knows you are but half a man—he has painted but one half of your face, and knows the other half is good for nothing!”

“Let the painter say it, and I will believe it—but when the Dog says it, let him prove it.”

“Shonka said it, and Shonka can prove it; if Mahtotcheega be a man and wants to be honored by the white men, let him not be ashamed—but let him do as Shonka has done: give the white man a horse, and then let him see the whole of your face without being ashamed.”

“When Mahtotcheega kills a white man and steals his horses, he may be ashamed to look at a white man until he brings him a horse! When Mahtotcheega waylays and murders an honorable and brave Sioux because he is a coward and not brave enough to meet him in fair combat, then he may be ashamed to look at a white man till he has given him a horse! Mahtotcheega can look at anyone, and he is now looking at an old woman and a coward!”

This repartee, which had lasted for a few minutes—to the amusement and excitement of the chiefs—ended thus: the Dog rose suddenly from the ground, and wrapping himself in his robe, left the wigwam, considerably agitated, having the laugh of all the chiefs upon him.

George Catlin

From Letters and Notes on the North American Indians. Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania in 1796, Catlin practiced law before turning to portrait painting in 1823. In 1830 he traveled to St. Louis with the intent of documenting the customs of the American Indians. He made more than five hundred paintings and sketches, the majority of which the Smithsonian Institution bought in 1879.