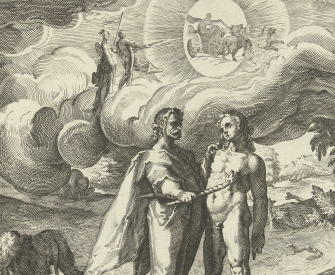

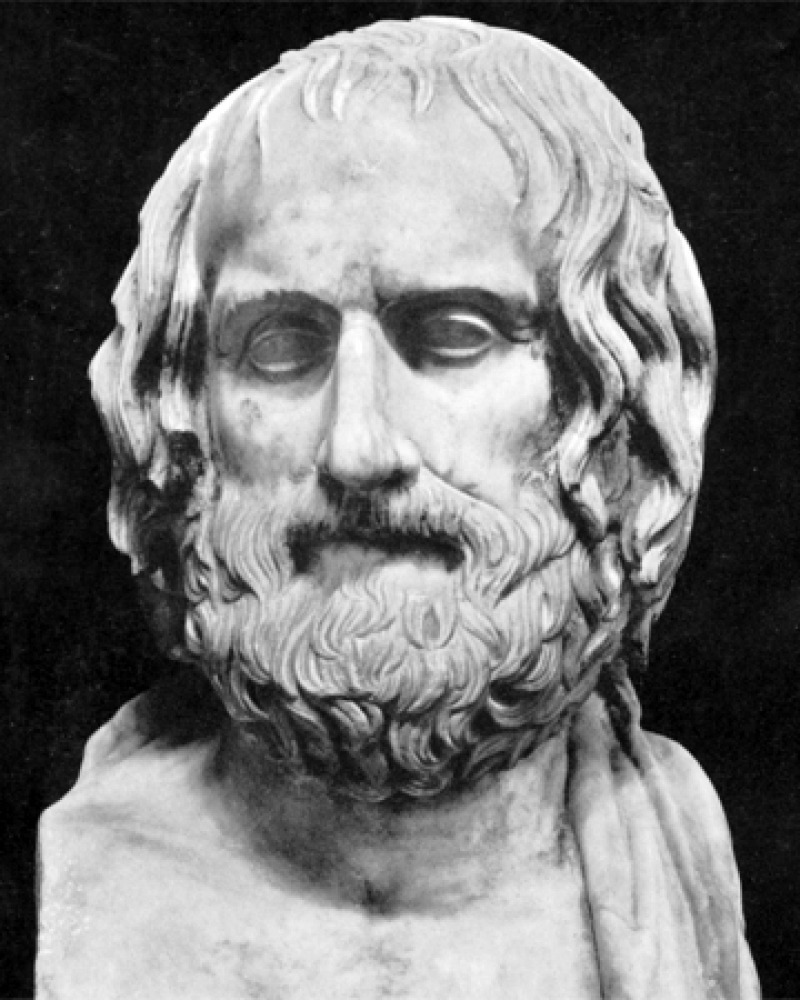

Euripides

Alcestis,

438 BC

Alcestis,

Admetos, you see my condition.

Now listen to my dying wish.

For you love these children no less than I.

Do not put a stepmother over them.

Let them be masters in this house,

not persecuted by some jealous second wife.

No—I beg you.

For a new wife hates the first children—

no gentler than a snake.

And a male child has a great tower in a father,

but you, my little girl,

how will your girlhood be with another mother?

What if she slanders you and ruins your chance of marriage?

For I will never adorn you as a bride

or encourage you in childbirth, dear one,

where a mother’s presence is a great solace.

Farewell and stay happy.

You, husband, say you had the best of wives.

And, O my children, that you had the best mother.