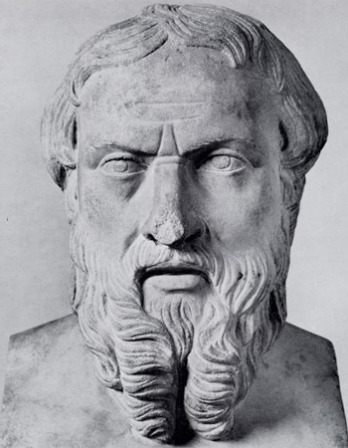

Plato

Phaedrus,

c. 370

Phaedrus,

Now here is what we must say about the soul’s structure. To describe what the soul actually is would require a very long account—altogether a task for a god in every way—but to say what it is like is humanly possible and takes less time. So let us do the second. Let us then liken the soul to the natural union of a team of winged horses and their charioteer. The gods have horses and charioteers that are themselves all good and come from good stock besides, while everyone else has a mixture. To begin with, our driver is in charge of a pair of horses; second, one of his horses is beautiful and good and from a stock of the same sort, while the other is the opposite and has the opposite sort of bloodline. This means that chariot driving in our case is inevitably a painfully difficult business.