We may learn both from the evidence of our senses and from experience that the inhabited world is an island; for wherever it has been possible for man to reach the limits of the earth, sea has been found, and this sea we call Oceanus.

And wherever we have not been able to learn by the evidence of our senses, there reason points the way. For example, as to the eastern (Indian) side of the inhabited earth, and the western (Ibero-Maurusian) side, one may sail wholly around them and continue the voyage for a considerable distance along the northern and southern regions; and as for the rest of the distance around the inhabited earth that has not been visited by us up to the present time (because of the fact that the navigators who sailed in opposite directions toward each other never met), it is not of very great extent, if we reckon from the parallel distances that have been traversed by us. It is unlikely that the Atlantic Ocean is divided into two seas, thus being separated by isthmuses so narrow and that prevent the circumnavigation; it is more likely that it is one confluent and continuous sea. For those who undertook circumnavigation and turned back without having achieved their purpose say that they were made to turn back not because of any continent that stood in their way and hindered their further advance, inasmuch as the sea still continued open as before, but because of their destitution and loneliness.

It is impossible for any man, whether layman or scholar, to attain to the requisite knowledge of geography without the determination of the heavenly bodies and of the eclipses that have been observed; for instance, it is impossible to determine whether Alexandria in Egypt is north or south of Babylon, or how much north or south of Babylon it is, without investigation through the means of the climata. In like manner, we cannot accurately fix points that lie at varying distances from us, whether to the east or the west, except by a comparison of the eclipses of the sun and the moon. All those who undertake to describe the distinguishing features of countries devote special attention to astronomy and geometry, in explaining matters of shape, size, distances between points, and climata, as well as matters of heat and cold, and, in general, the peculiarities of the atmosphere. Indeed, an architect in constructing a house, or an engineer in founding a city, would make provision for all these conditions; and all the more would they be considered by the man whose purview embraced the whole inhabited world.

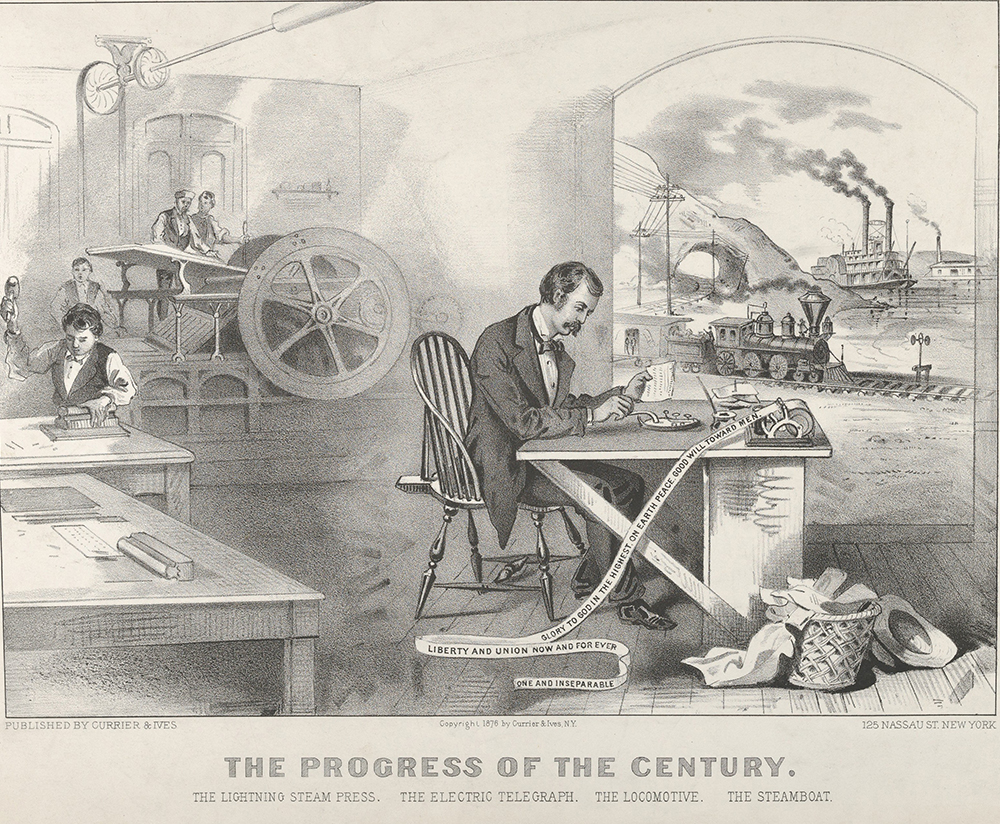

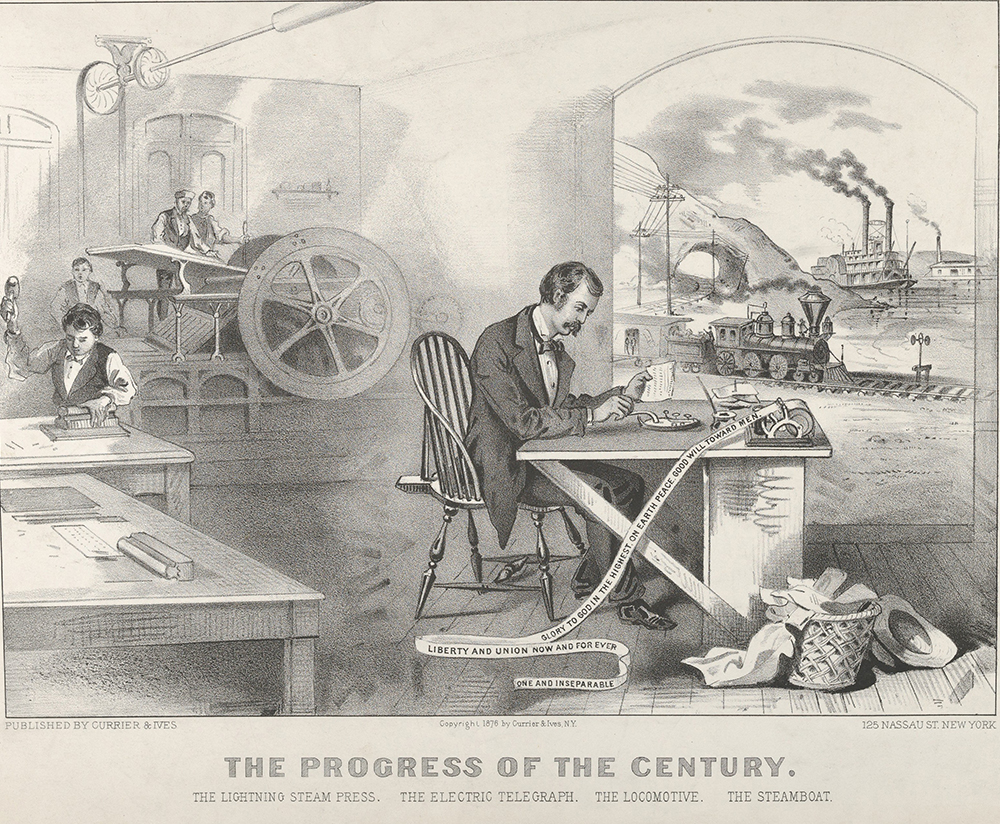

The Progress of the Century—The Lightning Steam Press, the Electric Telegraph, the Locomotive, the Steamboat, by Currier and Ives, 1876. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Adele S. Colgate, 1962.

To this encyclopedic knowledge, let us add terrestrial history—that is, the history of animals and plants and everything useful or harmful produced by land or sea. And to this knowledge, we must add a knowledge of all that pertains to the sea; for in a sense we are amphibious and belong no more to the land than to the sea. That the benefit is great to anyone who has become possessed of information of this character is evident both from ancient traditions and from reason. At any rate, the poets declare that the wisest heroes were those who visited many places and roamed over the world; for the poets regard it as a great achievement to have “seen the cities and known the minds of many men.” Nestor boasts of having lived among the Lapiths, to whom he had gone as an invited guest, “from a distant land afar—for of themselves they summoned me.” Menelaus, too, makes a similar boast when he says, “I roamed over Cyprus and Phoenicia and Egypt and came to Ethiopians and Sidonians and Erembians and Libya.” And it was undoubtedly because of Heracles’ wide experience and information that Homer speaks of him as the man who “had knowledge of great adventures.”

From Geography. Born circa 60 BC in Pontos, south of the Black Sea, Strabo—whose name means “squinter”—came to Rome around the time of Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC and soon became acquainted with the city’s community of Greek scholars. After completing a series of historical commentaries, he began his seventeen-volume Geography by the late 20s BC, traveling, researching, and writing the work until his death four decades later. The layered text, according to classicist Duane W. Roller, “is known to all, quoted by many, and understood by few.”

Back to Issue