Fire is a natural symbol of life and passion, though it is the one element in which nothing can actually live.

—Susanne K. Langer, 1942

A Ship in a Stormy Sea, by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky, 1892. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Isabel F. Hapgood, 1913.

In 1903 construction began on a railway line to connect Berlin and Baghdad. The new train route was to stretch nearly a thousand miles, beginning south of Ankara and extending through present-day Turkey, Syria, and Iraq before linking with the Tigris River and the Persian Gulf. As German engineers worked on the line in the years before the First World War, a small rail station to support the construction effort was built in the arid landscape of the Ottoman Empire. The site chosen was near an oasis that was once used to water horses by the army of Saladin, the famous sultan and military commander who pushed back European crusaders in the twelfth century. But by the early twentieth century the location appeared on scarcely any maps at all. As a settlement began to take shape around the station, the Kurds living in the area called the new town Kobani, after the German Bahn company that organized life there in its early years.

It was in this town that Alan Kurdi was born in 2013. By then, of course, the Germans were long gone. Following the Treaty of Versailles, the Ottoman Empire was split up, and the railway line formed part of the border between Turkey and Syria, with Kobani left on the Syrian side. Even though trains no longer ran between Syria and Germany, the Syrian civil war drove millions in precisely that direction, fleeing violence. Alan Kurdi, however, would never make it that far. As fighting ramped up in the months before the June 2015 Islamic State siege of Kobani, the Kurdi family took flight. They found a way over the border and traveled nearly a thousand miles to the Mediterranean, on Turkey’s western coast, hoping to sail the final few miles to Greece and the chance of asylum in Europe.

Alan Kurdi became known to the world in September 2015, when his drowned body washed up on a beach in the Turkish resort town of Bodrum. The photograph of the young boy lying facedown in the surf, his open palms floating at his side, was published on the front pages of newspapers across the world. The migration crisis had been going on for years, but this image jolted the public to attention. I remember when I first saw the picture. I was sitting in a busy café in Brooklyn, spending the afternoon working on my laptop. It seemed certain to become an icon of the tragic toll of the war.

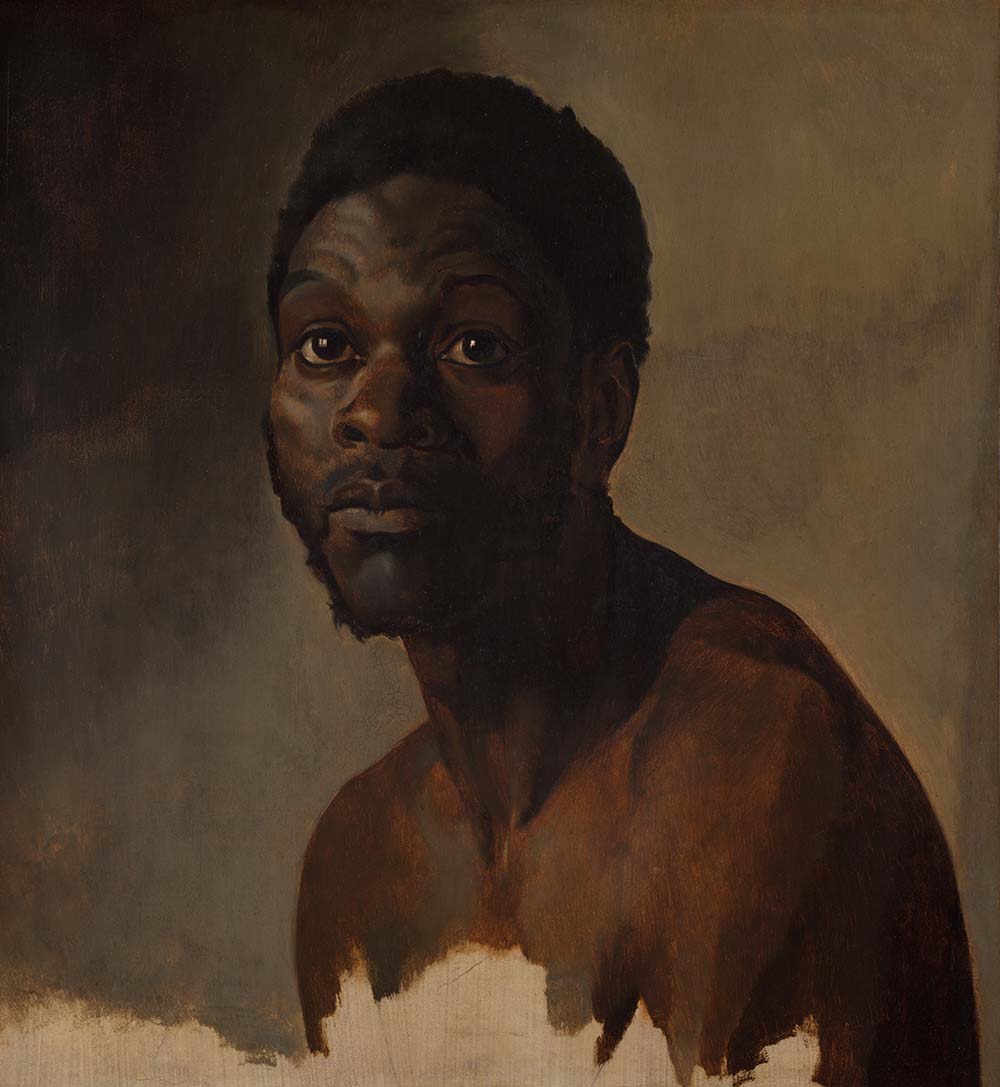

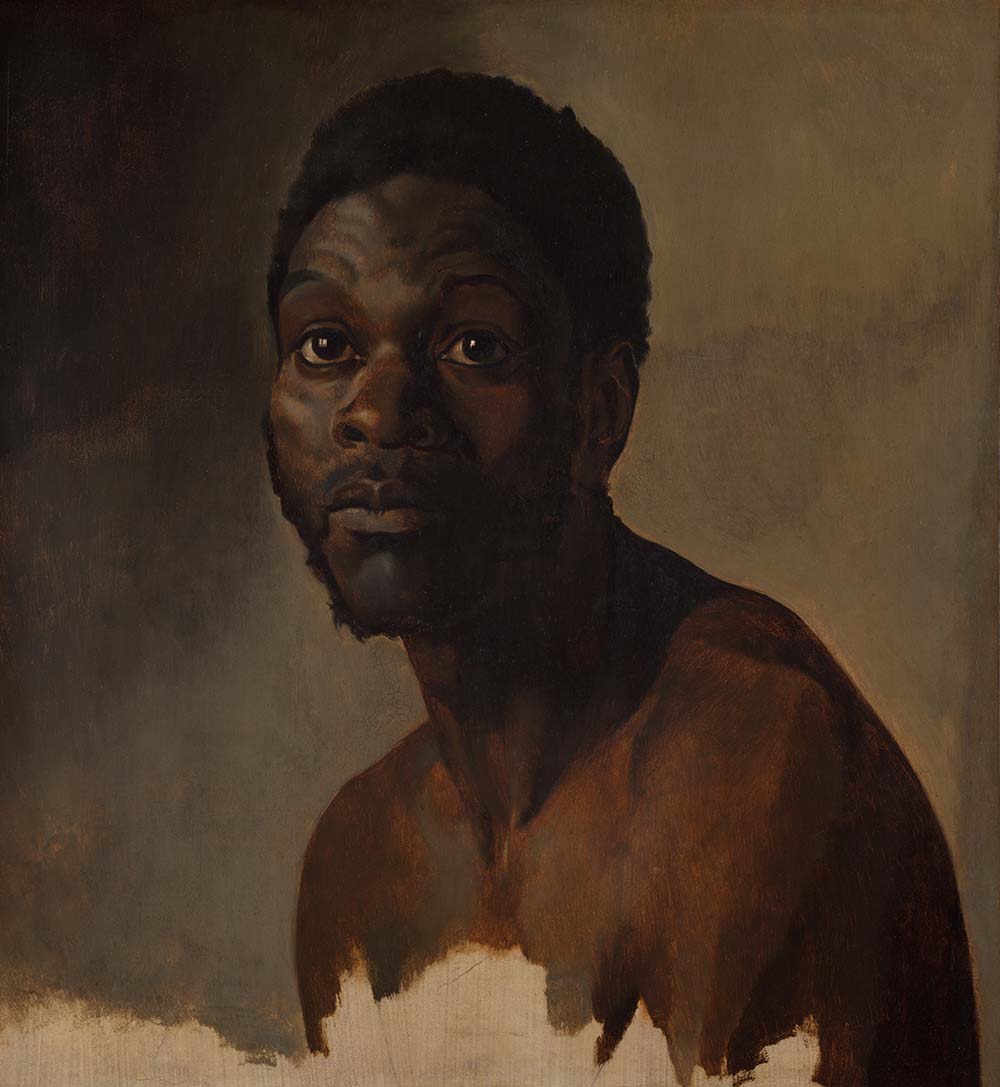

Bust-Length Study of a Man, by François-Auguste Biard, 1848. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Wolfe Fund and Wheelock Whitney III Gift, 2022.

Although the crisis has since faded from the headlines, the period following the Arab Spring was one of massive migration. The United Nations estimates that by the end of 2016 over five million people moved from the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa toward Europe. Austria and Hungary erected razor wire along their borders; Italy signed a secret deal with Libya to keep migrants away; and sprawling refugee camps emerged on the islands of Lesbos and Lampedusa. Germany, breaking from the pack, agreed to take a million migrants from the region, leading a short time later to members of a nationalist party claiming seats in the Bundestag for the first time since the Nazi era.

All these stories filled my head one day when I came upon an article describing how refugees used Google Maps and WhatsApp to coordinate their border crossings and evade authorities. Although it seems obvious that a huge number of migrants would have cell phones, I somehow hadn’t quite realized it before. Most newspaper coverage at the time told stories of statistics, of international concern, of gruesome events. Less often were the contents of suitcases discussed, or children being sent on before their parents, or bus tickets bought and smugglers consulted. In the midst of their uncertain journeys, many migrants were looking at the same devices and the same apps that I was, fingers instinctually reaching for the same green WhatsApp icon. The tracks of steel railroads did not connect us, but networks of fiber-optic cables certainly did, and they all ran through a shared pool of computer servers. The big tech companies that power these apps must have a deeply intimate perspective on what amounts to the largest human migration since the 1940s. This realization brought me back to Kobani and to the Turkish-Syrian border. What, I wondered, might be learned about the migration crisis through the world of these apps? Were there stories other than the ones in the newspaper? What kinds of things did the tech companies know?

I’ve always been fascinated by borders. In some ways, of course, they are a kind of fiction, one that frames stories and lives, cutting through the imagination. They are at once razor-sharp and paper-thin, invisible or insurmountable depending on the contents of your pocket. They are made of field surveys, topography, lines of sight, history, archives, satellite photography, and bored officials in dusty shacks drinking tea and checking papers. But to an app like Instagram, for example, they are something else entirely. To Instagram, the border is a collection of photos and user accounts, of IP addresses and latitudes and longitudes, of servers and blacklists, of who follows whom and who likes what.

When I got home that day, I went on Google Maps to find Kobani. I started scrolling my way along the border, first looking at satellite photos and then tracing the roads, searching for points where they crossed over into Turkey. Some of the checkpoints were large; others seemed no more than a small booth and a few vehicles. Eventually I made my way over to the Turkish border town of Nusaybin, just across from Qamishli in Syria. There was a hotel there named Avesis that had a Google rating of 4.6 stars. What would a well-reviewed hotel along the Syrian border be like? I wondered. As it turned out, the Avesis was one of the nicest hotels in the area: a new three-story concrete building. Its facade was inlaid with a mixture of neoclassical and neo-Ottoman flourishes, and a large red hotel avesis sign ran along the roof with three giant stars that could surely be seen far and wide across the flat, dusty terrain. As my explorations continued, I noticed that the hotel had an Instagram account. I started looking through it, and then I looked up other locations on the map not too far away. I was totally entranced, transported into a world that would consume much of my attention for the next year.

At first it was a donkey trotting along a dirt road. A boy in a red tank top is mounted on the animal as it moves toward us. It draws closer, and we can see another boy sitting just behind him. Is it his brother? The road curves and stretches back into the distance, where a group of small green buildings and a slender white minaret stand against a light-blue sky. Voices chatter unseen in the background, and a rough breeze skips over the microphone. The boy holds a long stick in one hand, and as the donkey takes its eager steps, the stick strikes its right haunch. The animal slows as it approaches the camera, and the boy looks straight at us, expectant and proud.

Now a man’s face fills the screen. He’s in his thirties, perhaps, his skin smooth but with heavy bags beneath his tired eyes. He, too, is traveling along a road, but this one is paved. He sits in an open trailer and seems always just about to speak. Where is he going? Why did he begin filming himself? The engine roars along with the wind as the man’s gaze drifts off into the distance. What thought causes him to snap his eyes back to the camera? He seems startled, as if trying not to slip into sleep.

Then there is a young woman on her wedding day. She stands in a voluminous white dress. A stream of sequins cascades down the skirt, and a long veil of lace and chiffon is pulled back over her head. Her father bends forward as he ties a red sash around her waist. His face is serious and focused on the task before him. The daughter looks toward her father’s hands as he works, her gaze shifting away from his face and then back again. Why does she begin to cry with almost her whole body? Her father smooths down the bow on her left hip, and the daughter bends forward to kiss his hand, moving it back and forth between her forehead and her lips, seeming not to want to let it go. The father pulls her up, kisses her on both cheeks and her forehead, and then surrounds her in a big hug.

Stag Hunt (detail), attributed to Huang Zongdao, c. 1120. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edward Elliott Family Collection, purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 1982

After spending some time exploring Instagram posts from the Turkish-Syrian border, I realized that this archive provided an incredible view into what life was like there. But it also raised several questions. Who were the people who were posting? What kinds of stories were being told? For whom? What fragments of quotidian experience might be found? What was missing? While millions of people crossed this border, would the lives of migrants themselves show up? And if not, and they existed only off-screen, then what other perspectives on the war might emerge?

Instagram does not make it easy to follow such threads. Over the years, the service has made it more difficult to search for images geographically or to download them in bulk. To investigate further, I knew I had to start scraping. Scraping is the technique by which people use computer programs to collect information from websites that are not easily searchable. Let’s say you want to gather the prices of every flight from Istanbul to Berlin (perhaps to create an alert when they drop below a certain level). You can write a computer program that runs every hour—or every minute—pretending to be a person searching for these flights to see what prices show up. Scraping a website requires a kind of archaeology: one must analyze the code to try to figure out how the engineers built it. By examining how the web browser in front of you talks to the distant server, one hopes to learn how it functions and how it can be imitated.

One of the most ubiquitous visual clichés of high-tech computer work is the streaming of cryptic—probably green—text down a monitor (think The Matrix). And while it almost never looks like that, it almost always does when one is web scraping, at least in the early stages. A program can visit many pages each second, and one needs to tend to its progress with nurturing care, expecting things to break along the way. As I scraped Instagram, the lines of text scrolled down my screen, and I watched a folder on my computer fill up with images and videos from the border. As the first ones started to appear, I was amazed by what I saw. A panoply of scenes accumulated: pharmacies, crossing points, refugee camps, hair salons, mangled bodies, protests, wedding venues, soldiers, food markets, roadside rest stops.

I opened a video file and was transported to the border. Suddenly the trilling screams of ecstatic women rise up all around. Is that gunfire? The camera moves excitedly, first along the ground and then upward. Who is holding it? An older woman—the family matriarch, perhaps?—clutches an AK-47. She is standing on a second-floor terrace and firing over lush green fields that extend all the way to the horizon. Empty shells chime unevenly as they fall onto the concrete floor. The camera turns to reveal a middle-aged man in a light-gray jacket. He looks almost bored as he watches the woman from the comfort of a couch. The old woman finishes shooting without ceremony and turns, walking out of the scene as she grasps the assault rifle by its neck, almost as if it were a garden spade or a chicken. Why was the woman shooting the gun? Was it a celebration? Was a son of the family going off to fight and his weapon being given some kind of blessing? Or were there merely some pests on the farm that needed to be scared off?

Bust-Length Study of a Man, by François-Auguste Biard, 1848. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Wolfe Fund and Wheelock Whitney III Gift, 2022.

Then, a bit further down in the folder, things had turned dark. We’re inside a speeding car, and a lone siren wails. The night is black, and only those objects touched by the headlights are visible. Now we’re out and running through the blackness. Footsteps and shouts fill the air. There are more and more people around. A flashlight cuts a path forward, and the vests of emergency workers in the distance reflect back the light. The anguished cries grow louder. A body we cannot see sags deeply in a brown blanket as it is carried out by several men. We take uneasy footsteps over a rubble-strewn path, and the faces of lost boys appear.

Scraping often involves a kind of cat-and-mouse game: a set of steps taken by the designers of web pages to control how they’re accessed, followed by the efforts of those interested in finding a way around them. The internet was once dreamed of as an open, borderless place where information would be free and accessible. But when the profits started to pile up, the walls climbed along with them. Lately, data has become subject to many of the same restrictions as people are. Governments around the world don’t like that U.S. or Chinese tech companies store data about their citizens and operate platforms that can spread politically threatening speech or be used for spying. This has led many governments to pass a slew of data-sovereignty laws that require companies to keep data about their citizens on servers located within their borders.

In 2018, as I was gathering videos from along the border, Turkey launched a military offensive against Kurdish communities living just on the other side, in and around the Syrian city of Afrin. The Turkish government demanded that Instagram’s parent company, Facebook, remove all posts from the People’s Protection Units, or YPG, a mostly Kurdish militia operating in the area, so that they could better control the narrative around the conflict. Emails from Facebook’s chief operating officer, Sheryl Sandberg, were subsequently leaked. “I’m fine with this,” she replied to a colleague in a terse email, showing with startling clarity how easily censorship can happen, transforming archives in the process.

Internet content can often feel dematerialized, but in fact there is a great chain of human hands relaying the bits of data along the way. Meta—the name of Facebook and Instagram’s parent company since late 2021—owns or rents servers in countries across the world, and the Instagram images I gathered passed through a series of them on the way to my screen in New York. Where were the people on the other side when they uploaded them? Perhaps some had their phones with them along the border and were connected to the Turkcell phone network. Once posted, the video would have traveled over a submarine cable to Cyprus before crossing the Turkish and Greek parts of the island and entering another submarine cable, which could eventually carry the data to 60 Hudson Street, an old art deco building in Manhattan that is a major switching station for transatlantic data, before finding its way to me.

Energy is the power that drives every human being. It is not lost by exertion but maintained by it, for it is a faculty of the psyche.

—Germaine Greer, 1970We hear only the severe sounds of Turkish rap as we drive down a street in Afrin, looking out over the sand-colored turret of a tank. The roads are empty, and it seems there was street fighting here not long ago. As the procession of armored vehicles continues, crowds of people appear, lining the street. They stand watching the tanks. No one smiles. Is this what a conquered city looks like? Another military vehicle approaches from the other direction. A boyish soldier mans the turret, but the machine gun is covered partially with a towel—does this keep it cool under the harsh sun? We’re now face-to-face with the boy. His grin extends from ear to ear, and he waves his hand at us, back and forth, back and forth. Is it the sad people that excite him so?

Suddenly we are very close to the rocky, monochrome ground, looking straight down. A shadow dominates the center of the screen, and then a roaring, high-pitched buzz builds rapidly—almost resembling a swarm of insects—and we are up and away. The shadow comes into focus, and it’s clear that this drone has six different propellers at the end of long arms extending out in a circle. The scene resembles a rover landing on Mars but here played in reverse. We are now high above the ground looking down on a building—a house, perhaps?—surrounded by a walled orchard. An object roughly the size of a large soda bottle enters the frame. As the bomb tumbles down to earth, it drifts toward a courtyard in front of the building. A triumphal song in auto-tuned Arabic—an anthem of the Islamic State—builds as the moment of impact approaches. A plume of dust and smoke rises, and figures can be seen running away.

Some time later, I started to find posts by a pharmacist. He is not too far from the Turkish town of Kilis, which is a short drive from Aleppo, in Syria. He sits in front of a row of sparsely filled shelves as he starts recording himself in black and white. A fax machine and a jumble of wires sit in one corner, some razors and other convenience items in another. The man takes a beat as he inhales. He begins to sing and draws his left arm upward, rolling his head toward the ceiling. Something in his motions seems exaggerated, a performance of deep feeling that is belied by a mischievous smile and the chaos of the shop. Now his right hand enters the frame with a lit cigarette. He raises it up to meet his gaze. It becomes clear that he is singing to the cigarette, expressing frustration and disgust. But then his voice softens and his hand begins tracing the rising trills of his voice, in what now sounds almost like a lullaby of affection.

The 566-mile line that separates Turkey and Syria was an invention of French diplomats and Turkish nationalists in 1930. Today, however, it has also grown to become something mapped and documented in the proprietary corporate databases of Meta. Over three million people crossed this border during the civil war, but which of their faces could be found among Instagram posts situated along it? Although these images represent only the smallest sliver of what Meta has in its vaults, such an archive still seems endless. How can one think about what kind of totality it represents?

Reviewing such an archive involves countless hours of exploration in a sea of material that is usually visited only by indifferent algorithms looking for something statistically significant. Yet to see posts from people in the midst of war—sometimes on the sidelines at a safe remove, sometimes right in the middle of it—presents a profound contrast to the images that usually circulate in the media. We are accustomed to scenes of violence and oppression from this part of the world, snapshots of destroyed buildings, of explosions in the distance. But through archives like this, a more complicated picture becomes visible. Quiet stories and fragments of life come to the surface, allowing a sense of intimacy to develop through videos made by bored truck drivers waiting to cross the border, Italian war tourists joking around with Kurdish fighters, or a father crying as he sends his daughter off on her wedding day.

At the start there’s always energy.

—Suzan-Lori Parks, 2006Like closed cities, the archives of companies like Meta are restricted areas that cannot be easily visited. These archives are instead cordoned off for the consumption of algorithms such as those that ultimately generate Meta’s nearly trillion-dollar market capitalization. The inherent value of such images on a large scale means there is little incentive for companies to make them more broadly accessible. This opacity gives big tech companies a monopoly of vision on the unfolding events of world history and a powerful influence over the kinds of stories that can be told about them.

What will the afterlives of these images be once they disappear from our feeds? Archives like these form a boundary between memory and forgetting; they connect the past to the present and, depending on decisions made today, will shape what can be imagined and remembered in the future. There are groups like the Syrian Archive project, which combs through this kind of data looking for documentation of war crimes in hopes that one day it can be brought before a court as evidence. But for the most part, this stuff accumulates in unseen data centers, forming a dizzyingly diverse archive of twenty-first-century life. Will stories from these archives continue to emerge over the years and decades to come, like the hidden cities we find periodically from forgotten civilizations? Or will today’s corporate data dynasties keep them locked away forever?