I cannot too strongly insist upon the need of a return to the method of old times. Our ancestors, when about to build a town or an army post, sacrificed some of the cattle that were wont to feed on the site proposed and examined their livers. If the livers of the first victims were dark colored or abnormal, they sacrificed others, to see whether the fault was due to disease or their food.

They never began to build defensive works in a place until after they had made many such trials and satisfied themselves that good water and food had made the liver sound and firm. If they continued to find it abnormal, they argued from this that the food and water supply found in such a place would be just as unhealthy for man, and so they moved away and changed to another neighborhood, healthfulness being their chief object.

If the walled town is built among the marshes themselves, provided they are by the sea, with a northern or northeastern exposure, and are above the level of the seashore, the site will be reasonable enough. For ditches can be dug to let out the water to the shore, and also in times of storms, the sea swells and comes backing up into the marshes, where its bitter blend prevents the reproductions of the usual marsh creatures, while any that swim down from the higher levels to the shore are killed at once by the salt to which they are unused. An instance of this may be found in the Gallic marshes surrounding Altino, Ravenna, Aquileia, and other towns in places of the kind, close by marshes. They are marvelously healthy, for the reasons I have given.

But marshes that are stagnant and have no outlets either by rivers or ditches, like the Pontine Marshes, merely putrefy as they stand, emitting heavy, unhealthy vapors. A case of a town built in such a spot was Old Salapia in Apulia, founded by Diomedes on his way back from Troy or, according to some writers, by Elpias of Rhodes. Year after year there was sickness, until finally the suffering inhabitants came with a public petition to Marcus Hostilius and got him to agree to seek and find them a proper place to which to remove their city. Without delay he made the most skillful investigations and at once purchased an estate near the sea in a healthy place and asked the Senate and Roman people for permission to remove the town. He constructed the walls and laid out the house lots, granting one to each citizen for a mere trifle. This done, he cut an opening from a lake into the sea and thus made of the lake a harbor for the town. The result is that now the people of Salapia live on a healthy site and at a distance of only four miles from the old town.

From On Architecture. Little is known of Vitruvius’ life beyond certain details contained in this ten-book treatise on architecture, urban planning, and engineering. The work appears to have been written shortly after Augustus, to whom it is dedicated, began a systematic renovation of Rome’s public buildings and aqueducts in 27 bc. Situated near the Adriatic coast of Apulia, the original site of Salapia was surrounded by former salt marshes. Soil runoff, resulting from the introduction of intensive agriculture to the region, had transformed them into brackish lakes of the kind preferred by malaria-bearing mosquitoes.

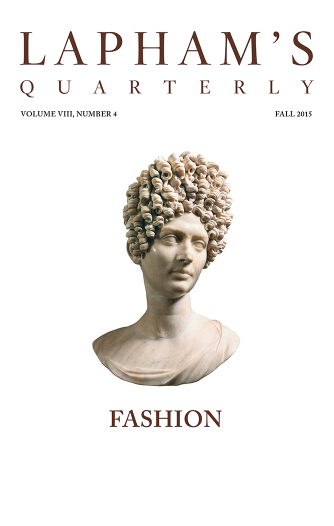

Back to Issue