The sick man is the parasite of society.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, 1889Duty Free

Mary Shelley presents a leader unequal to the moment.

Circumstances had called me to London; here I heard talk that symptoms of the plague had occurred in hospitals of that city.

I returned to Windsor; my brow was clouded, my heart heavy; I entered the Little Park, as was my custom, at the Frogmore gate, on my way to the castle. A great part of these grounds had been given to cultivation, and strips of potato land and corn were scattered here and there. The rooks cawed loudly in the trees above; mixed with their hoarse cries, I heard a lively strain of music. It was my son Alfred’s birthday. The young people, the Etonians, and children of the neighboring gentry held a mock fair, to which all the country people were invited. The park was speckled by tents, whose flaunting colors and gaudy flags, waving in the sunshine, added to the gaiety of the scene. On a platform erected beneath the terrace, a number of the younger part of the assembly were dancing. I leaned against a tree to observe them. The band played the wild eastern air of Weber introduced in Abon Hassan; its volatile notes gave wings to the feet of the dancers, while the lookers-on unconsciously beat time. At first the tripping measure lifted my spirit with it, and for a moment my eyes gladly followed the mazes of the dance. The revulsion of thought passed like keen steel to my heart. Ye are all going to die, I thought; already your tomb is built up around you. Awhile, because you are gifted with agility and strength, you fancy that you live; but frail is the “bower of flesh” that encaskets life; dissoluble the silver cord that binds you to it. The joyous soul, charioted from pleasure to pleasure by the graceful mechanism of well-formed limbs, will suddenly feel the axletree give way, and spring and wheel dissolve in dust. Not one of you, O fated crowd, can escape—not one! Not my own ones! Not my most affectionate wife, Idris, and her babes! Horror and misery!

I felt that this was insanity—I sprang forward to throw it off; I rushed into the midst of the crowd. Idris saw me; with light step she advanced; as I folded her in my arms, feeling, as I did, that I thus enclosed what was to me a world, yet frail as the waterdrop which the noonday sun will drink from the water lily’s cup; tears filled my eyes, unwont to be thus moistened. The earth reeled, the firm-enrooted trees moved—dizziness came over me—I sank to the ground.

My beloved friends were alarmed—nay, they expressed their alarm so anxiously that I dared not pronounce the word plague that hovered on my lips, lest they should construe my perturbed looks into a symptom and see infection in my languor. I had scarcely recovered, and with feigned hilarity had brought back smiles into my little circle, when we saw Ryland approach.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, by Albrecht Dürer, c. 1497. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Felix M. Warburg, 1940.

Ryland had something the appearance of a farmer, of a man whose muscles and full-grown stature had been developed under the influence of vigorous exercise and exposure to the elements. This was to a great degree the case: for though a large landed proprietor, yet, being a projector, and of an ardent and industrious disposition, he had on his own estate given himself up to agricultural labors. When he went as ambassador to the Northern States of America, he, for some time, planned his entire migration, and went so far as to make several journeys far westward on that immense continent, for the purpose of choosing the site of his new abode. Ambition turned his thoughts from these designs—ambition, which laboring through various lets and hindrances, had now led him to the summit of his hopes, in making him Lord Protector of England.

His countenance was rough but intelligent: his ample brow and quick gray eyes seemed to look out over his own plans and the opposition of his enemies. His voice was stentorian; his hand stretched out in debate seemed, by its gigantic and muscular form, to warn his hearers that words were not his only weapons. Few people had discovered some cowardice and much infirmity of purpose under this imposing exterior. No man could crush a “butterfly on the wheel” with better effect, no man better cover a speedy retreat from a powerful adversary. In the unsteady glance of his eye, in his extreme desire to learn the opinions of all, in the feebleness of his handwriting, these qualities might be obscurely traced, but they were not generally known. He was now our Lord Protector. He had canvassed eagerly for this post. His protectorate was to be distinguished by every kind of innovation on the aristocracy. This his selected task was exchanged for the far different one of encountering the ruin caused by the convulsions of physical nature. He was incapable of meeting these evils by any comprehensive system; he had resorted to expedient after expedient and could never be induced to put a remedy in force till it came too late to be of use.

Certainly the Ryland that advanced toward us now bore small resemblance to the powerful, ironical, seemingly fearless canvasser for the first rank among Englishmen. Our native oak, as his partisans called him, was visited truly by a nipping winter. He scarcely appeared half his usual height; his joints were unknit, his limbs would not support him; his face was contracted, his eye wandering; debility of purpose and dastard fear were expressed in every gesture.

In answer to our eager questions, one word alone fell, as it were involuntarily, from his convulsed lips: The plague—“Where?”—“Everywhere—we must fly—all fly—but whither? No man can tell—there is no refuge on earth, it comes on us like a thousand packs of wolves—we must all fly—where shall you go? Where can any of us go?”

These words were syllabled trembling by the iron man. Adrian, the Earl of Windsor, replied, “Whither indeed would you fly? We must all remain and do our best to help our suffering fellow creatures.”

“Help!” said Ryland, “There is no help!—great God, who talks of help! All the world has the plague!”

“Then to avoid it, we must quit the world,” observed Adrian, with a gentle smile.

Ryland groaned; cold drops stood on his brow. It was useless to oppose his paroxysm of terror; but we soothed and encouraged him, so that after an interval he was better able to explain to us the ground of his alarm. It had come sufficiently home to him. One of his servants, while waiting on him, had suddenly fallen down dead. The physician declared that he died of the plague. We endeavored to calm him—but our own hearts were not calm. I saw the eye of Idris wander from me to her children, with an anxious appeal to my judgment. Adrian was absorbed in meditation. For myself, I own that Ryland’s words rang in my ears; all the world was infected—in what uncontaminated seclusion could I save my beloved treasures, until the shadow of death had passed from over the earth? We sank into silence, a silence that drank in the doleful accounts and prognostications of our guest.

We had receded from the crowd and, ascending the steps of the terrace, sought the castle. Our change of cheer struck those nearest to us; and by means of Ryland’s servants, the report soon spread that he had fled from the plague in London. The sprightly parties broke up—they assembled in whispering groups. The spirit of gaiety was eclipsed; the music ceased; the young people left their occupations and gathered together. The lightness of heart which had dressed them in masquerade habits, had decorated their tents, and assembled them in fantastic groups, appeared a sin against, and a provocative to, the awful destiny that had laid its palsying hand upon hope and life. The merriment of the hour was an unholy mockery of the sorrows of man. The foreigners whom we had among us, who had fled from the plague in their own country, now saw their last asylum invaded; and fear making them garrulous, they described to eager listeners the miseries they had beheld in cities visited by the calamity and gave fearful accounts of the insidious and irremediable nature of the disease.

We had entered the castle. Idris stood at a window that overlooked the park; her maternal eyes sought her own children among the young crowd. An Italian lad had got an audience about him and, with animated gestures, was describing some scene of horror. Alfred stood immovable before him, his whole attention absorbed. Either watching the crowd in the park or occupied by painful reflection, we were all silent; Ryland stood by himself in an embrasure of the window; Adrian paced the hall, revolving some new and overpowering idea—suddenly he stopped and said, “I have long expected this; could we in reason expect that this island should be exempt from the universal visitation? The evil is come home to us, and we must not shrink from our fate. What are your plans, my Lord Protector, for the benefit of our country?”

“For heaven’s love! Windsor,” cried Ryland, “do not mock me with that title. Death and disease level all men. I neither pretend to protect nor govern a hospital—such will England quickly become.”

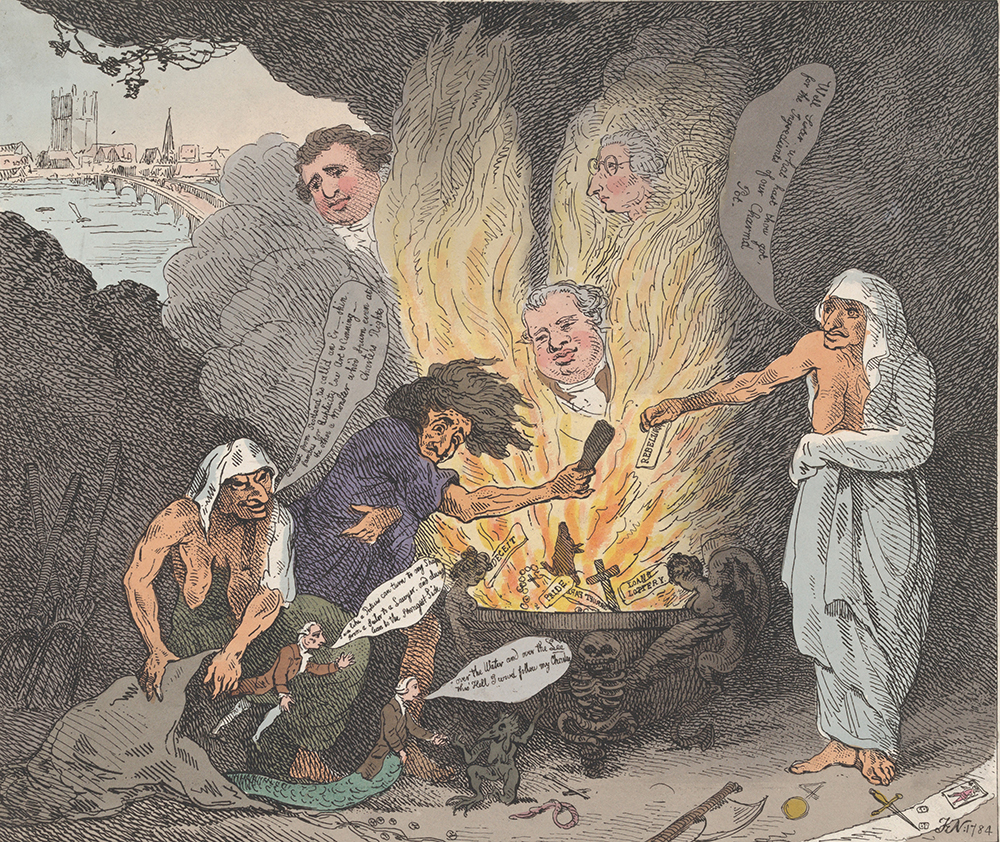

The Pit of Acheron, or The Birth of the Plagues of England, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1784. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Elisha Whittelsey Collection, Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.

“Do you then intend, now in time of peril, to recede from your duties?”

“Duties! Speak rationally, my Lord!—When I am a plague-spotted corpse, where will my duties be? Every man for himself! The devil take the protectorship, say I, if it expose me to danger!”

“Fainthearted man!” cried Adrian indignantly. “Your countrymen put their trust in you, and you betray them!”

“I betray them!” said Ryland. “The plague betrays me. Fainthearted! It is well, shut up in your castle, out of danger, to boast yourself out of fear. Take the protectorship who will; before God I renounce it!”

“And before God,” replied his opponent fervently, “do I receive it! No one will canvass for this honor now—none envy my danger or labors. Deposit your powers in my hands. Long have I fought with death, and much” (he stretched out his thin hand) “much have I suffered in the struggle. It is not by flying but by facing the enemy that we can conquer. If my last combat is now about to be fought, and I am to be worsted—so let it be!

“But come, Ryland, recollect yourself! Men have hitherto thought you magnanimous and wise; will you cast aside these titles? Consider the panic your departure will occasion. Return to London. I will go with you. Encourage the people by your presence. I will incur all the danger. Shame, shame, if the first magistrate of England be foremost to renounce his duties!”

Meanwhile, among our guests in the park, all thoughts of festivity had faded. As summer flies are scattered by rain, so did this congregation, late noisy and happy, in sadness and melancholy murmurs break up, dwindling away apace. With the set sun and the deepening twilight, the park became nearly empty. Adrian and Ryland were still in earnest discussion. We had prepared a banquet for our guests in the lower hall of the castle; and thither Idris and I repaired to receive and entertain the few that remained. There is nothing more melancholy than a merry meeting thus turned to sorrow: the gala dresses—the decorations, gay as they might otherwise be, receive a solemn and funereal appearance. If such change be painful from lighter causes, it weighed with intolerable heaviness from the knowledge that the earth’s desolator had at last, even as an archfiend, lightly overleaped the boundaries our precautions raised and at once enthroned himself in the full and beating heart of our country.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

From The Last Man. Shelley published this novel in 1826, eight years after the publication of Frankenstein and within a decade of the deaths of her husband, her friend Lord Byron, and three of her four children. The novel is set in a future in which a plague has ravaged humanity, ending with the titular protagonist, Lionel Verney, setting sail in search of fellow survivors. Ryland, the newly elected Lord Protector of England, absconds to the north after the plague crosses the English Channel. He is later found dead, eaten away by bugs and surrounded by “piles of food laid up in useless superfluity.”