I think we are inexterminable, like flies and bedbugs.

—Robert Frost, 1959Aboard the Titanic

Luck comes to an unlucky place.

To begin at the beginning, I joined the Titanic at Belfast. I was born at Nunhead, England, twenty-two years ago and joined the Marconi wireless telegraph forces last July. I first worked on the Hoverford and then on the Lusitania.

I didn’t have much to do aboard the Titanic except to relieve the first wireless officer, Phillips, from midnight until some time in the morning, when he should be through sleeping. On the night of the accident I was not sending but was asleep. I was due to be up and relieve Phillips earlier than usual. And that reminds me—if it hadn’t been for a lucky thing we never could have sent any call for help.

The lucky thing was that the wireless broke down early enough for us to fix it before the accident. We noticed something wrong on Sunday, and Phillips and I worked seven hours to find it. We found a “secretary” burned out, at last, and repaired it just a few hours before the iceberg was struck.

Phillips said to me as he took the night shift, “You turn in, boy, and get some sleep, and go up as soon as you can and give me a chance. I’m all done for with this work of making repairs.”

There were three rooms in the wireless cabin. One was a sleeping room, one a dynamo room, and one an operating room. I took off my clothes and went to sleep in bed. Then I was conscious of waking up and hearing Phillips sending to Cape Race. I read what he was sending. It was traffic matter.

I remembered how tired he was, and I got out of bed without my clothes on to relieve him. I didn’t even feel the shock. I hardly knew it had happened after the captain had come to us. There was no jolt whatever.

I was standing by Phillips telling him to go to bed when the captain put his head in the cabin.

The Destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, by Francisco Hayez, 1867. © Cameraphoto Arte, Venice / Art Resource.

“We’ve struck an iceberg,” the captain said, “and I’m having an inspection made to tell what it has done for us. You had better get ready to send out a call for assistance. But don’t send it until I tell you.”

The captain went away and in ten minutes, I should estimate the time, he came back. We could hear a terrible confusion outside, but there was not the least thing to indicate that there was any trouble. The wireless was working perfectly.

“Send the call for assistance,” ordered the captain, barely putting his head in the door.

“What call should I send?” Phillips asked.

“The regulation international call for help. Just that.”

Then the captain was gone. Phillips began to send “CQD.” He flashed away at it, and we joked while he did so. All of us made light of the disaster.

We joked that way while he flashed signals for about five minutes. Then the captain came back.

“What are you sending?” he asked.

“CQD,” Phillips replied.

The humor of the situation appealed to me. I cut in with a little remark that made us all laugh, including the captain.

“Send ‘SOS,’ ” I said. “It’s the new call, and it may be your last chance to send it.”

Phillips with a laugh changed the signal to “SOS.” The captain told us we had been struck amidships, or just back of amidships. It was ten minutes, Phillips told me, after he had noticed the iceberg that the slight jolt that was the collision’s only signal to us occurred. We thought we were a good distance away.

We said lots of funny thing to each other in the next few minutes. We picked up first the steamship Frankfurt. We gave her our position and said we had struck an iceberg and needed assistance. The Frankfurt operator went away to tell his captain.

He came back and we told him we were sinking by the head. By that time we could observe a distinct list forward.

The Carpathia answered our signal. We told her our position and said we were sinking by the head.

I heard Phillips giving the Carpathia fuller directions. Phillips told me to put on my clothes. Until that moment I forgot that I was not dressed.

I went to my cabin. I brought an overcoat to Phillips. It was very cold. I slipped the overcoat upon him while he worked.

Every few minutes Phillips would send me to the captain with little messages. They were merely telling how the Carpathia was coming our way and gave her speed.

I noticed as I came back from one trip that they were putting off women and children in lifeboats. I noticed that the list forward was increasing.

Phillips told me the wireless was growing weaker. The captain came and told us our engine rooms were taking water and that the dynamos might not last much longer.

I went out on deck and looked around. The water was pretty close up to the boat deck. There was a great scramble aft, and how poor Phillips worked through it I don’t know.

He was a brave man. I learned to love him that night, and I suddenly felt for him a great reverence to see him standing there sticking to his work while everybody else was raging about.

I thought it was about time to look about and see if there was anything detached that would float. I remembered that every member of the crew had a special lifebelt, and ought to know where it was. I remembered mine was under my bunk. I went and got it. Then I thought how cold the water was.

I remembered I had some boots and I put these on, and an extra jacket and I put that on. I saw Phillips standing out there still sending away, giving the Carpathia details of just how we were doing.

I saw a collapsible boat near a funnel and went over to it. Twelve men were trying to boost it down to the boat deck. They were having an awful time. It was the last boat left. I looked at it longingly a few minutes. Then I gave them a hand, and over she went. They all started to scramble in on the boat deck, and I walked back to Phillips. I said the last raft had gone.

Then came the captain’s voice: “Men, you have done your full duty. You can do no more. Abandon your cabin. Now it’s every man for himself. You look out for yourselves. I release you. That’s the way of it at this kind of time. Every man for himself.”

I looked out. The boat deck was awash. Phillips clung on sending and sending. He clung on for about ten minutes or maybe fifteen minutes after the captain had released him. The water was then coming into our cabin.

While he worked something happened I hate to tell about. I was back in my room getting Phillips’ money for him, and as I looked out the door I saw a stoker, or somebody from below decks, leaning over Phillips from behind. He was too busy to notice what the man was doing. The man was slipping the lifebelt off Phillips’ back.

He was a big man, too. I don’t know what it was I got hold of. I remembered in a flash the way Phillips had clung on—how I had to fix that lifebelt in place because he was too busy to do it.

I knew that man from below decks had his own lifebelt and should have known where to get it.

I suddenly felt a passion not to let that man die a decent sailor’s death. I wished he might have stretched rope or walked a plank. I did my duty. I hope I finished him. I don’t know. We left him on the cabin floor of the wireless room and he was not moving.

From aft came the tunes of the band. It was a ragtime tune; I don’t know what. Phillips ran aft, and that was the last I ever saw of him alive.

I went to the place I had seen the collapsible boat on the boat deck, and to my surprise I saw the boat and the men still trying to push it off. I guess there wasn’t a sailor in the crowd. They couldn’t do it. I went up to them and was just lending a hand when a large wave came awash of the deck.

The big wave carried the boat off. I had hold of an oarlock and I went off with it. The next I knew I was in the boat.

But that was not all. I was in the boat and the boat was upside down and I was under it. And I remember realizing I was wet through, and that whatever happened I must not breathe, for I was underwater.

I knew I had to fight for it, and I did. How I got out from under the boat I do not know, but I felt a breath of air at last.

There were men all around me—hundreds of them. The sea was dotted with them, all depending on their lifebelts. I felt I simply had to get away from the ship. She was a beautiful sight then. Smoke and sparks were rushing out of her funnel. There must have been an explosion, but we had heard none. We only saw the big stream of sparks. The ship was gradually turning on her nose—just like a duck does that goes down for a dive. I had only one thing on my mind—to get away from the suction. The band was still playing. I guess all of the band went down.

They were playing “Autumn” then. I swam with all my might. I suppose I was 150 feet away when the Titanic, on her nose, with her after-quarter sticking straight up in the air, began to settle—slowly.

When at last the waves washed over her rudder there wasn’t the least bit of suction I could feel. She must have kept going just so slowly as she had been.

I felt, after a little while, like sinking. I was very cold. I saw a boat of some kind near me and put all my strength into an effort to swim to it. It was hard work. I was all done when a hand reached out from the boat and pulled me aboard. It was our same collapsible. The same crowd was on it.

There was just room for me to roll on the edge. I lay there, not caring what happened. Somebody sat on my legs. They were wedged in between slats, and were being wrenched. I had not the heart left to ask the man to move. It was a terrible sight all around—men swimming and sinking.

I lay where I was, letting the man wrench my feet out of shape. Others came near. Nobody gave them a hand. The bottom-up boat already had more men than it would hold, and it was sinking.

At first the larger waves splashed over my clothing. Then they began to splash over my head, and I had to breathe when I could.

As we floated around on our capsized boat, and I kept straining my eyes for a ship’s lights, somebody said, “Don’t the rest of you think we ought to pray?” The man who made the suggestion asked of what religion the others were. Each man called out his religion. One was a Catholic, one a Methodist, one a Presbyterian.

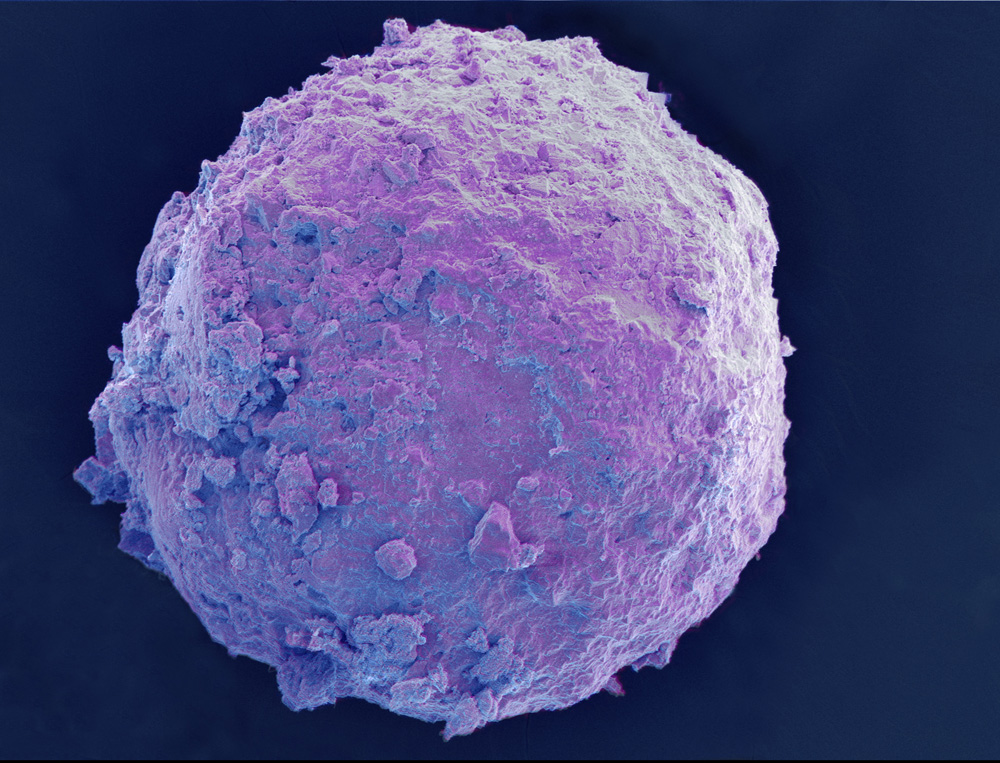

Meteorite from the K-T extinction event, SEM micrograph by Edward Kinsman. © Edward Kinsman / Science Source / Getty Images.

It was decided the most appropriate prayer for all was the Lord’s Prayer. We spoke it over in chorus with the man who first suggested that we pray as the leader.

Some splendid people saved us. They had a right-side-up boat, and it was full to its capacity. Yet they came to us and loaded us all into it. I saw some lights off in the distance and knew a steamship was coming to our aid.

I didn’t care what happened. I just lay and gasped when I could and felt the pain in my feet. At last the Carpathia was alongside, and the people were being taken up a rope ladder. Our boat drew near, and one by one the men were taken off of it.

One man was dead. I passed him and went to the ladder, although my feet pained terribly. The dead man was Phillips. He had died on the raft from exposure and cold, I guess. He had been all in from work before the wreck came. He stood his ground until the crisis had passed, and then he had collapsed, I guess.

But I hardly thought that then. I didn’t think much of anything. I tried the rope ladder. My feet pained terribly, but I got to the top and felt hands reaching out to me. The next I knew a woman was leaning over me in a cabin, and I felt her hand waving back my hair and rubbing my face.

I felt somebody at my feet, and felt the warmth of a jolt of liquor. Somebody got me under the arms. Then I was bustled down below to the hospital. That was early in the day I guess. I lay in the hospital until near night, and they told me the Carpathia’s wireless man was getting “queer” and would I help.

After that I never was out of the wireless room, so I don’t know what happened among the passengers. I saw nothing of Mrs. Astor or any of them. I just worked wireless. The splutter never died down. I knew it soothed the hurt and felt like a tie to the world of friends and home.

How could I then take news queries? Sometimes I let a newspaper ask a question and got a long string of stuff asking for full particulars about everything. Whenever I started to take such a message I thought of the poor people waiting for their messages to go—hoping for answers to them.

I shut off the inquiries and sent my personal messages. And I feel I did the right thing.

There were maybe one hundred left. I would like to send them all, because I could rest easier if I knew all those messages had gone to the friends waiting for them.

The way the band kept playing was a noble thing. I heard them first while still we were working wireless, when there was a ragtime tune for us, and the last I saw of the band, when I was floating out in the sea with my lifebelt on, they were still on deck playing “Autumn.” How they ever did it I cannot imagine.

Harold Bride

From an account in the New York Times. Bride received a thousand dollars from the Times for his story, told in the presence of his boss, wireless telegraph inventor Guglielmo Marconi. (Marconi was already in New York, having forgone free passage on the Titanic and taken the Lusitania three days earlier.) The SOS signal had been officially adopted by an international convention in 1906, but Marconi company operators still preferred the older, conventional distress signal of CQD, the company’s own standard.