Is it only the mouth and belly which are injured by hunger and thirst? Men’s minds are also injured by them.

—Mencius, 300 BCThe Imperial Kitchen

Ottoman cuisine developed over centuries as the imperial center of an empire of food.

By Jason Goodwin

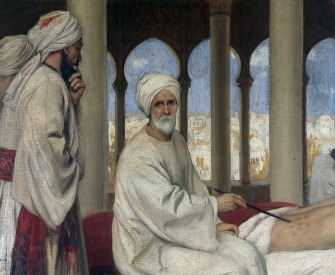

Sultan Selim III holding an audience in front of the Gate of Felicity.

Twenty years ago, I walked across Eastern Europe to Istanbul. The food, on the whole, was plain, but from Bulgaria we walked through a gathering rush of portents—strong coffee and orthodox domes, bright prints and the eastern rhythm of gypsy music—until we reached The City, and began to eat.

We ate fish in a restaurant suspended under the old Galata Bridge, watching the ferries come and go. We ate mutton and eggplant wrapped in a paper parcel in the Grand Bazaar. Bread of exceptional freshness appeared at every restaurant table. Cauldrons bubbled, full of sweet or spicy vegetable stews, to be eaten with morsels of tender lamb, marinated, spitted, and roasted over the charcoal braziers whose scent drifted through the air. We found sustaining dishes of beans, the large white kind, and everywhere rice, especially pilaf with golden chickpeas (I did not know then that Mahmut Pasha, one of the great fifteenth-century grand viziers, put real gold chickpeas in his pilaf to delight his guests, like sixpence in the Christmas pudding). Down on the shores of the Golden Horn we bought mackerel sandwiches, the fish just taken from the Bosporus, filleted and grilled on the boats. After months of Soviet-style scarcity and monotony, Istanbul was like a gingerbread house.

It had its fairy-tale palace too. Set on the first of the city’s seven hills, overlooking the Bosporus and the Asian coast, Topkapi Palace was home to the Ottoman sultans from shortly after the conquest in 1453 until the nineteenth century. It is not a typical castle or stately home. The Turks were firstly nomads, and Topkapi most resembles an encampment in stone, a collection of fossilized tents and open spaces. A wit once remarked that it looked as if it had been shaken out of a bag. But what thrilled foreign visitors to the marrow during the Ottoman period was the human architecture of the place, the rows of utterly silent, immobile janissaries standing guard around the walls of the court, the silent servants, the bowing slaves, all bearing witness to the sultan’s absolute authority over men.

Deer hunt, from the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, Netherlands, c. 1445. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Among the kiosks, halls, reception chambers, and harem baths, I suspect that visitors today spend the least time of all in the palace kitchens—unless they have an interest in Chinese porcelain, which is displayed in there. Otherwise there’s nothing much to see, just a series of domed rooms. Outside you can count the ten pairs of massive chimneys, but there’s no smoke.

It’s a pity that the building is so quiet, because it was in here, over four centuries, that one aspect of Istanbul’s imperial purpose was most vividly expressed. The imperial kitchen quarters extended well beyond the great domed chambers, each of which was devoted to particular specialties, such as the making of sweets, pickles, and cures. There were pantries and storerooms and offices for the team of clerks who kept meticulous records of what was bought, and how much was spent. Hundreds of men, commanded by sixty specialty chefs, lived and worked here, feeding up to ten thousand people a day. The soup, the pilaf, the helva, the vegetable dishes, meats, breads, pastries were each produced by a master chef, with as many as a hundred apprentices. They had their own dormitories, a fountain, a mosque, and a hammam where they could bathe.

Stupendous quantities of food came into the palace. In 1723, for example, the imperial household consumed thirty thousand head of beef, sixty thousand of mutton, twenty thousand of veal, ten thousand of kid, 200,000 of fowl, 100,000 pigeons and three thousand turkeys. That was the butcher’s bill. About fifty years earlier, half a million bushels of chickpeas and twelve thousand pounds of salt were delivered to the palace kitchens. The palace tore through food like the city that surrounded it—in 1581 eight ships from Egypt brought grain sufficient to feed the city for a single day.

The city lay at the confluence of many currents of trade, drawn across an empire that stretched from the Balkans to Egypt, and from the borders of Georgia to the Adriatic. Egypt was the Ottoman’s granary. Anatolia was their fruit bowl. The mountain pastures of Europe and Asia provided them with sweet mutton and cheese. Every region had its specialty, like the delicate and delicious trout of Lake Ohrid, on the border between Macedonia and Albania, which were carried overland, live, to Topkapi Palace for the sultan’s feasts. The best of everything arrived there in its season—watermelon and green onions from Bursa, figs from the Aegean coast, fruit from the Black Sea. Vegetables came from market gardens snuggled up beneath the ancient Byzantine walls, within living memory, and different districts of the city became famous for certain products, like the clotted cream of Eyüp, or the flaky pastries of Karaköy. Meanwhile, the finest garlic came from İzmit, lemons from Mersin, cheeses in skins from the mountains of Moldavia. This was an imperial palace in a city of imperial appetite, and not for nothing has the palace cookery of Istanbul been defined along with the Chinese and the French as one of the three great food cultures of the world.

It was in the palace kitchens that for four hundred years all this rich pharmacopoeia was mediated into a cuisine, as you can tell from the lubricious names of various recipes: women’s thighs, young girl’s breasts, ladies’ navels, and the like. It was served much as it had been a thousand years previously among the Uighur tribes, on a low table, eaten with spoons and the fingers. Until the nineteenth century, when French styles began to be adopted, there were no dining rooms, no special dining tables or chairs: the Ottomans never had rooms spookily empty and unused for most of the day and night. Their meals were eaten sitting around a low table called a sofra, which was set up wherever they wanted. A few meze [appetizer] dishes would decorate the tray, and each dish was placed on the sofra as it arrived. Western visitors were astonished how quickly, and silently, people ate; the diners only had a few mouthfuls from each dish, presumably left for the servants, who took them all away at the end of the meal.

Here is Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, a sixteenth-century Flemish ambassador, on a palace reception:

The banquet was given in the garden, and the pasha and the ambassador sat under an awning…Some hundred servants dressed in identical outfits were lined up, all equally spaced out, from the pantry to the sofra. First they placed their hands on their hips and bowed their heads in greeting. Then they started serving the meal. The servant standing next to the pantry took the dish of food and passed it to the servant standing next to him, and he passed it to the next. Thus the food was passed all the way to the servant standing next to the sofra, and he placed it on the sofra. There were maybe more than a hundred dishes, and they were all passed in this way with no confusion and utterly smoothly. After this task was finished, the servants again bowed their respects, and starting with the ones right at the back, they retreated, walking backward.

The janissaries, the Ottoman’s crack troops, and the first standing army in Europe since Rome’s, also used food to organize themselves, taking their ranks from the commissariat. The divisional commanders were known as soup men; other ranks variously as chief cook, scullion, baker, and pancake maker. Although these titles soon became symbolic, the heart of the janissary regiment still remained its kazgan, or cauldron, in which the regimental pilaf was cooked: the terrible noise of the men drumming with their spoons on an upturned cauldron—rejecting the sultan’s rice, in effect—was the city’s signal for a mutiny. By the eighteenth century, when the empire had entered its long decline, janissary mutinies were regular, and intimidating, events—until in 1826 the regiments were finally suppressed.

By then, the janissaries were scarcely distinguishable from the ordinary artisans of the city, members of the various trade guilds which protected and regulated their production, including, naturally, the many guilds involved in selling, transporting, and preparing food. For there was food wherever you looked, sizzling on the street as well as simmering in the palace. One of the grandest markets was the Egyptian Bazaar, right on the waters of the Golden Horn, whose stones still leak the scents of ambergris and coriander, pepper and mastic, saffron and cinnamon and rosewater (rosewater used for the infusion of saffron, for rice dishes: coriander, curiously, has slipped from the Turkish repertoire). Every district had its market, and fish were sold fresh from the deep waters of the Bosporus, not to mention the anchovies which, along the Black Sea coast, were used even to make bread.

All this required cooking—but you didn’t ever have to cook, because the streets not only teemed with people from every corner of this vast, heterogeneous empire—Greeks and Turks, of course, Armenians and Jews, Laz and Georgians, Serbs, Arabs, and the odd Frank—but with wandering peddlers and fast-food shacks. Rigorously patrolled by the cadis, who exacted summary punishment for infringement of the rules, these street vendors were even unwittingly patronized by sultans, who might wander incognito through the streets (Osman III ate roasted chickpeas, kebabs, and a sort of griddled and buttered toast called gözleme). Thirsty, you beckoned the sherbet seller, the waterman, the orange-juice vendor, each with his tank and his tube, his glasses and his tray, his unique patter and paraphernalia. Today you can buy roasted chestnuts, or a bag of stuffed mussels, or stop a simit seller for a ring of bread like a pretzel, although the glory days are gone, banished by health and safety directives more draconian and dismal than any sultan’s decree. As the Turks grow richer, so food is gradually banished from the street.

Food is not only an expression of power; it is gossip, and friendship, too, represented by the meze prepared for an evening of conversation. Meze can include the class of dishes called dolma, meaning stuffed; stuffed vine leaves—dolmades—from Greece are well-known. The Ottomans could stuff anything, from a mackerel to a leek. The New World vegetables which are now the staple of any Mediterranean kitchen did not become widespread until the nineteenth century: dishes which once relied on pomegranate molasses might now be sweetened with tomatoes instead. Leeks and onions, cabbage and fava beans, spinach and other greens, and of course the sultan of the Turkish kitchen, eggplant, were the ordinary vegetables of the Ottomans; Mehmed the Conqueror once had his gardeners disemboweled in order to establish which of them had stolen a cucumber from the imperial garden. Nor for the most part did the Turks cook with oil, preferring butter or even mutton fat, though the repertoire now contains a number of dishes, usually served as meze, which are cooked specifically á l’huile d’olive. They have entered the Western tradition as, for example, mushrooms á la Grecque, sweated in oil, seasoned with lemon juice, and served at room temperature.

Stuffing peppers is child’s play. You mix together a couple of finely chopped onions, three-quarters of a pound ground lamb, not too lean, and a generous handful of rice with four or five chopped tomatoes, in a bowl. Season the mix with bunches of chopped parsley, dill, mint, a sprig of thyme, half a teaspoon of ground cumin, and another of allspice; salt and pepper to taste. Loosen the mix with a cup of water and let it stand for half an hour. Take the tops off half a dozen red and green bell peppers, fill them with the mixture, clap their lids on again, and bake, standing in a cupful of water or stock, until the peppers are done.

Food, food, and more food! The maw of the imperial capital was stuffed by laws of requisition, which extended to the hills of Moldavia and the Anatolian heartlands. There, only the surplus could be sold at market rates; for the rest the administration set prices, and quantities, with military precision, guaranteeing that in a given year 200,000 head of cattle would be brought into the city slaughterhouses (35,000 were used to make pastirma, a cousin of pastrami). And the sultan, by tradition, fed his people in a society where largesse was the measure of dignity. Everywhere were public kitchens serving pilaf to the poor, and the year proceeded with a round of public feasts, linked to religious ceremonies like the night of the Prophet’s birth or the end of Ramadan, not to mention innumerable celebration feasts for imperial circumcisions and weddings.

Scholars argue over the origins of Ottoman cuisine, Greeks and Turks still skirmishing in the kitchen. Off the Eurasian steppe, where they lived as nomads, the Turks took yogurt and cheese, and many traditions of bread, brushing up against the Chinese empire to adopt manti, or dumplings. As they moved through the Middle East, they encountered the sophisticated cuisine of Persia, considered the France of the East. The cookery writer and historian Ayla Algar reckons the Ottomans’ meat and fruit stews, as well as their vegetable stews or yahni, to represent that inheritance. Kebab is a word of Persian origin, as is pilaf: it’s hard to believe that kebab was not already grilled by nomads, but rice was cultivated in Iran and the rest of the Middle East, not on the steppes; it is thought by some to have been a benign inheritance from the Mongols, who from the borders of China devastated much of the Middle East in the thirteenth century. Meanwhile, in Anatolia, the Turks stepped into a land from which many common foods are supposed to have originated—the vine, as well as many familiar fruit and nut trees; here, too, they encountered the use of olive oil, and of course fish, many names for which often entered Turkish through the Greek. “To the Turks, God gave the land,” an old saying runs, “and to the Greeks, the sea.” But it remains hard to say how far Ottoman cookery was influenced by the Byzantine tradition.

The Decadence of the Romans, by Thomas Couture, 1847. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Ottoman palace practice traveled out across the empire, spread by the Ottoman elite, men who had graduated from the palace service. To this day, dolma and kofta, kebabs and baklava, good yogurt and flaky pastries are made in places as far apart as Egypt and Albania. The essential components of a meal have scarcely changed since Ottoman times; now as then, they include meze, soups, rice dishes, grilled meats, vegetable stews, and pastries.

Meze can be found all across the Mediterranean, similar to Spanish tapas or Venetian cicchetti—and to my mind they are particularly good in Lebanon. Meze are small dishes, tastes, usually composed of vegetables and fish, which can be as simple as glistening black olives or a tiny, fresh cucumber dipped in rough salt. Even the more complex dishes, like stuffed mussels or cigarette borek, are eaten at room temperature, and they are meant to accompany drinks, especially raki, the aniseed liquor popular all over Turkey and as arak or ouzo familiar to travelers elsewhere in the region.

Soups are abundant. Lentil soup, made with dumplings; tripe soup, considered a hangover cure; one of the hallmarks of good cooking—which the Turks share with the French and the Chinese—is a well-developed interest in using everything up, and turning the most sinister offal into a treat. Modern cookbooks often don’t bother with a recipe for tripe soup. You take two pounds of beef tripe and simmer it with garlic, lemon juice, olive oil, and salt for four hours, until the tripe is soft, skimming off the scum and adding water to keep the tripe submerged. This is cooking as a dark art—and worth it, if you can stomach tripe. Now cut the tripe up into half-inch squares, make a roux in a separate saucepan, adding the cooking water slowly, followed by a cup of milk and the chopped tripe. Simmer for half an hour and serve seasoned with a splash of white-wine vinegar, a generous scrunch of pepper and some chopped garlic. This is a very, very old recipe, and its earthy flavor will leave you ready to attack Belgrade, or to sack Isfahan.

Fish, for the most part, is simply grilled—a lesson plenty of Western cooks would do well to learn, if they could have it fresh. It is served hot with sliced raw onion and a drizzle of oil, maybe mixed with lemon juice; sometimes it is wrapped in vine or fig leaves, to protect it from the flames. Kakavia, a fish stew considered by some to be the original bouillabaisse, is a Greek fisherman’s dish. When Turks talk of meat, they generally mean lamb, stewed or grilled. For a feast, the whole beast is spatchcocked on a wooden cross, rubbed with salt and oil, spiked with rosemary and thyme, and suspended over a pit of flaming charcoal; as the coals subside, the lamb is gradually lowered into the pit, and finally—like a clambake—sealed into it with brushwood and clay.

Buttery pilafs are made with rice or bulgar. The secret to cooking rice so that the grains are tender and separate is steam. You wash the rice thoroughly to remove the starch and soak it for half an hour. To a given quantity of rice add one-and-a-half times as much boiling water and boil vigorously until the water is absorbed and the surface of the rice pitted with holes like moon craters. The grains should be nutty and slightly undercooked. Stir in knobs of butter and a little ground cinnamon, then cover the pan with a cloth and remove from the heat. In about fifteen minutes you can fluff the rice with a fork, and serve.

One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well.

—Virginia Woolf, 1929The dishes are prepared: the sultan will eat. As each dish leaves the kitchen, it is placed in a silver vessel closed by a wax seal, as a precaution against tampering. Eagle eyes keep watch as the food is handed up to the sultan’s sofra, where he eats alone—for the sultan, in a tradition established by Mehmed II after the conquest of Constantinople, always dines alone. He is not, quite, an ordinary mortal.

And yet he eats, as mortals must. Surrounded by pomp, fawned upon by courtiers, imprisoned by rigmarole and tradition, he craves simplicity. What he desires is not a Mughal feast, lacquered in gold; nor a Medici banquet, full of masquerades and music. He is an Ottoman, and his tastes are naturally refined. He doesn’t need to be tricked; he wants to be transported.

And so consider this old recipe for eggs with onions, soganli yumurta. It was a dish traditionally served to the sultan on the fifteenth day of Ramadan, to break the fast; if the chef’s efforts pleased the sultan, he could be promoted to head of the pantry. The recipe itself is pure simplicity, and would delight supporters of the Slow Food movement; it is also truly sophisticated. Half a dozen sweet onions are sliced finely, salted, and then gently melted with butter in a shallow pan over a very low heat for three hours. Into this rich, creamy paste, the cook puts a splash of vinegar, a couple of spoonfuls of sugar, a generous pinch of allspice, and lets it all mix in well. He makes little pockets in the mix with the back of a wooden spoon and breaks a half dozen eggs into them, covering the pan to cook very gently for another ten minutes, now and again spooning the juice over the eggs. Soganli yumurta is served with black pepper and cinnamon sprinkled on top. You don’t need three hours, one will do; but then you will never be head of the pantry at Topkapi Palace.