All men naturally hate each other. We have used concupiscence as best we can to make it serve the common good, but this is mere sham and a false image of charity, for essentially it is just hate.

—Blaise Pascal, 1655Paul Gauguin Reborn

“All the joys—animal and human—of a free life are mine.”

I understand the Maori tongue well enough by now, and it will not be long before I speak it without difficulty.

My neighbors—three of them quite close by, and many more at varying distances from each other—look upon me as one of them.

Under the continual contact with the pebbles my feet have become hardened and used to the ground. My body, almost constantly nude, no longer suffers from the sun.

Civilization is falling from me little by little.

I am beginning to think simply, to feel only very little hatred for my neighbor—rather, to love him.

All the joys—animal and human—of a free life are mine. I have escaped everything that is artificial, conventional, customary. I am entering into the truth, into nature. Having the certitude of a succession of days like this present one, equally free and beautiful, peace descends on me. I develop normally and no longer occupy myself with useless vanities.

I have won a friend.

He came to me of his own accord, and I feel sure here that in his coming to me there was no element of self-interest.

He is one of my neighbors, a very simple and handsome young fellow.

My colored pictures and carvings in wood aroused his curiosity; my replies to his questions have instructed him. Not a day passes that he does not come to watch me paint or carve…

Even after this long time I still take pleasure in remembering the true and real emotions in this true and real nature.

In the evening when I rested from my day’s work, we talked. In his character of a wild young savage he asked many questions about European matters, particularly about the things of love, and more than once his questions embarrassed me.

But his replies were even more naive than his questions.

One day I put my tools in his hands and a piece of wood; I wanted him to try to carve. Nonplussed, he looked at me at first in silence, and then returned the wood and tools to me, saying with entire simplicity and sincerity, that I was not like the others, that I could do things which other men were incapable of doing, and that I was useful to others.

I indeed believe Totefa is the first human being in the world who used such words toward me. It was the language of a savage or of a child, for one must be either one of these—must one not?—to imagine that an artist might be a useful human being.

It happened once that I had need of rosewood for my carving. I wanted a large strong trunk, and I consulted Totefa.

“We have to go into the mountains,” he told me. “I know a certain spot where there are several beautiful trees. If you wish it I will lead you. We can then fell the tree which pleases you and together carry it here.”

We set out early in the morning.

The footpaths in Tahiti are rather difficult for a European, and “to go into the mountains” demands even of the natives a degree of effort which they do not care to undertake unnecessarily.

Between two mountains, two high and steep walls of basalt, which it is impossible to ascend, there yawns a fissure in which the water winds among rocks. These blocks have been loosened from the flank of the mountain by infiltrations in order to form a passageway for a spring. The spring grew into a brook, which has thrust at them and jolted them, and then moved them a little further. Later the brook, when it became a torrent, took them up, rolled them over and over, and carried them even to the sea. On each side of this brook, frequently interrupted by cascades, there is a sort of path. It leads through a confusion of trees—breadfruit, ironwood, pandanus, bouraos, coconut, hibiscus, guava, giant ferns. It is a mad vegetation, growing always wilder, more entangled, denser, until, as we ascend toward the center of the island, it has become an almost impenetrable thicket.

Both of us went naked, the white and blue pareu around the loins, hatchet in hand. Countless times we crossed the brook for the sake of a shortcut. My guide seemed to follow the trail by smell rather than by sight, for the ground was covered by a splendid confusion of plants, leaves, and flowers which wholly took possession of space.

The silence was absolute but for the plaintive wailing of the water among the rocks. It was a monotonous wail, a plaint so soft and low that it seemed an accompaniment of the silence.

And in this forest, this solitude, this silence were we two—he, a very young man, and I, almost an old man from whose soul many illusions had fallen and whose body was tired from countless efforts, upon whom lay the long and fatal heritage of the vices of a morally and physically corrupt society.

With the suppleness of an animal and the graceful litheness of an androgyne he walked a few paces in advance of me. And it seemed to me that I saw incarnated in him, palpitating and living, all the magnificent plant life which surrounded us. From it in him, through him there became disengaged and emanated a powerful perfume of beauty.

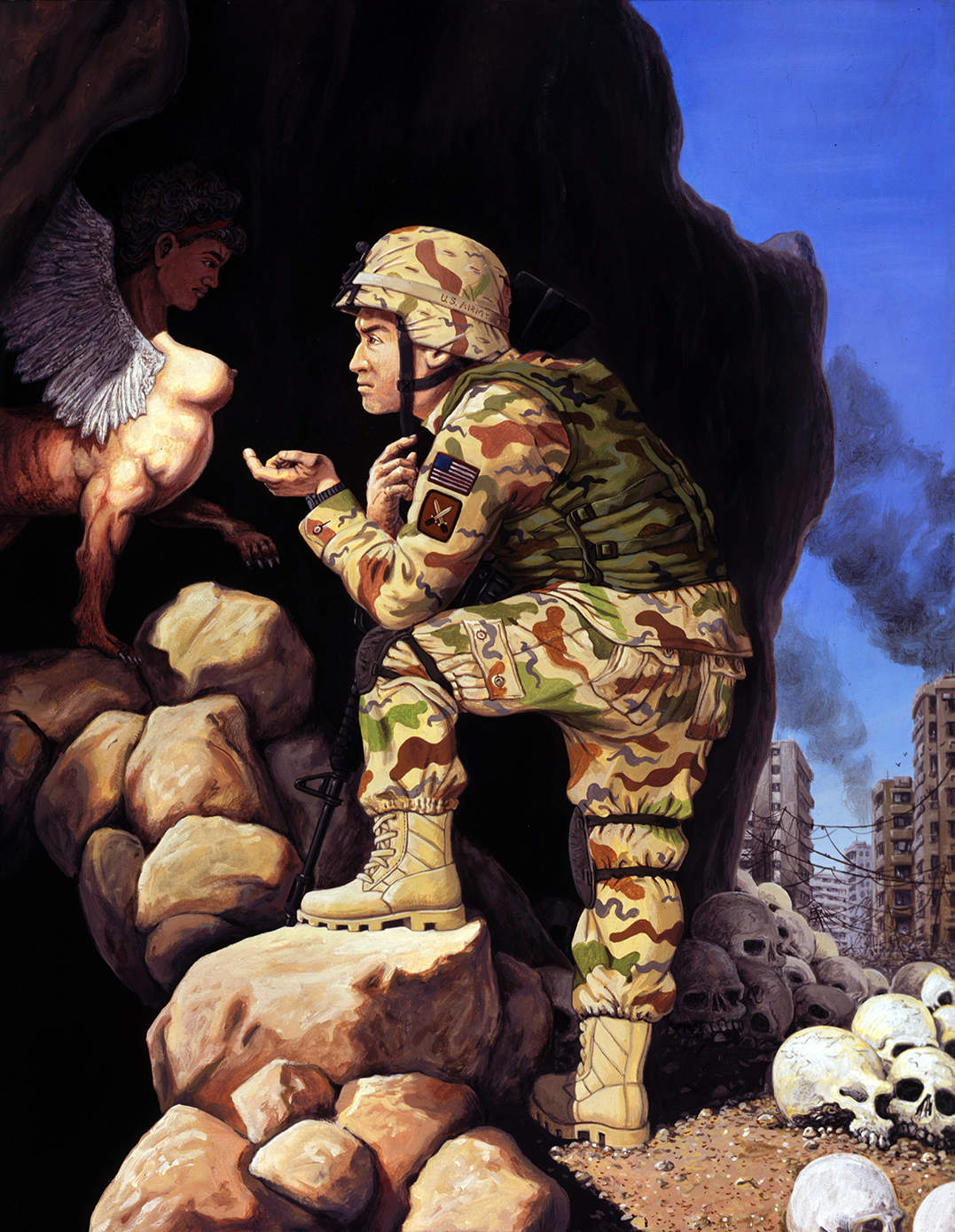

The Riddle of the Sphinx, by Sandow Birk, 2007. Oil on canvas, 34 x 22 inches. © Sandow Birk, courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

Was it really a human being walking there ahead of me? Was it the naive friend by whose combined simplicity and complexity I had been so attracted? Was it not rather the forest itself, the living forest, without sex—and yet alluring?

Among peoples that go naked, as among animals, the difference between the sexes is less accentuated than in our climates. Thanks to our cinctures and corsets we have succeeded in making an artificial being out of woman. She is an anomaly, and nature herself, obedient to the laws of heredity, aids us in complicating and enervating her. We carefully keep her in a state of nervous weakness and muscular inferiority, and in guarding her from fatigue, we take away from her possibilities of development. Thus modeled on a bizarre ideal of slenderness to which, strangely enough, we continue to adhere, our women have nothing in common with us, and this, perhaps, may not be without grave moral and social disadvantages.

On Tahiti the breezes from forest and sea strengthen the lungs, they broaden the shoulders and hips. Neither men nor women are sheltered from the rays of the sun nor the pebbles of the seashore. Together they engage in the same tasks with the same activity or the same indolence. There is something virile in the women and something feminine in the men.

This similarity of the sexes make their relations the easier. Their continual state of nakedness has kept their minds free from the dangerous preoccupation with the “mystery” and from the excessive stress which among civilized people is laid upon the “happy accident” and the clandestine and sadistic colors of love. It has given their manners a natural innocence, a perfect purity. Man and woman are comrades, friends rather than lovers, dwelling together almost without cease, in pain as in pleasure, and even the very idea of vice is unknown to them.

In spite of all this lessening in sexual differences, why was it that there suddenly rose in the soul of a member of an old civilization, a horrible thought? Why, in all this drunkenness of lights and perfumes with its enchantment of newness and unknown mystery?

The fever throbbed in my temples and my knees shook.

But we were at the end of the trail. In order to cross the brook my companion turned, and in this movement showed himself full face. The androgyne had disappeared. It was an actual young man walking ahead of me. His calm eyes had the limpid clearness of waters.

Peace forthwith fell upon me again.

We made a moment’s halt. I felt an infinite joy, a joy of the spirit rather than of the senses, as I plunged into the fresh water of the brook.

“Toë, toë,” it is cold, said Totefa.

“Oh, no!” I replied.

This exclamation seemed to me also a fitting conclusion to the struggle which I had just fought out within myself against the corruption of an entire civilization. It was the end in the battle of a soul that had chosen between truth and untruth. It awakened loud echoes in the forest. And I said to myself that nature had seen me struggle, had heard me, and understood me, for now she replied with her clear voice to my cry of victory that she was willing after the ordeal to receive me as one of her children.

We took up our way again. I plunged eagerly and passionately into the wilderness, as if in the hope of thus penetrating into the very heart of this nature, powerful and maternal, there to blend with her living elements.

With tranquil eyes and ever uniform pace my companion went on. He was wholly without suspicion; I alone was bearing the burden of an evil conscience.

We arrived at our destination.

Such then is the human state, that to wish greatness for one’s country is to wish harm to one’s neighbors.

—Voltaire, 1764The steep sides of the mountain had by degrees spread out, and behind a dense curtain of trees, there extended a sort of plateau, well concealed. Totefa, however, knew the place, and with astonishing sureness led me there.

A dozen rosewood trees extended their vast branches.

We attacked the finest of these with the axe. We had to sacrifice the entire tree to obtain a branch suitable for my project.

I struck out with joy. My hands became stained with blood in my wild rage, my intense joy of satiating within me I know not what divine brutality. It was not the tree I was striking, it was not it which I sought to overcome. And yet gladly would I have heard the sound of my axe against other trunks when this one was already lying on the ground.

And here is what my axe seemed to say to me in the cadence of its sounding blows:

Strike down to the root the forest entire!

Destroy all the forest of evil,

Whose seeds were once sowed within thee by the breathings of death!

Destroy in thee all love of the self!

Destroy and tear out all evil, as in the autumn we cut with the hand the flower of the lotus.

Yes, wholly destroyed, finished, dead, is from now on the old civilization within me. I was reborn; or rather another man, purer and stronger, came to life within me.

This cruel assault was the supreme farewell to civilization, to evil. This last evidence of the depraved instincts which sleep at the bottom of all decadent souls, by very contrast exalted the healthy simplicity of the life at which I had already made a beginning into a feeling of inexpressible happiness. By the trial within my soul mastery had been won. Avidly I inhaled the splendid purity of the light. I was, indeed, a new man; from now on I was a true savage, a real Maori.

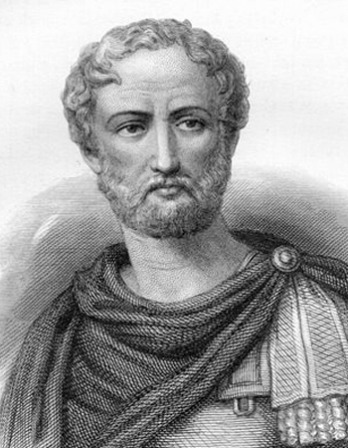

Paul Gauguin

From Noa Noa. Having spent time on the island of Martinique in 1887 hoping “to live like a savage,” Gauguin decided to travel three years later to Tahiti, receiving a government subsidy to visit the French colony and “to study and then paint the customs and landscapes” that he encountered. With the help of poet Charles Morice, he composed Noa Noa in France, intending it to complement his new body of work on sale at a one-man show in 1893. He left again for Tahiti in 1895, never to return, and died in the Marquesas in 1903.