We have really everything in common with America nowadays, except, of course, language.

—Oscar Wilde, 1887With the Refugees

Mattathias Schwartz follows would-be immigrants.

Walk west, into the desert. Take figs, water, money, a mobile phone. Rest during the bright part of the day. Walk toward sunset. Walk through the night. On the third or fourth day, you will come to a road. Ask the way to the city. Ask and walk, ask and walk, until you reach Khartoum, Sudan. Find someone to hold your money, someone trustworthy. The kind of person who answers their phone. From here on, the journey is more difficult, more costly. Take care with choosing your guide. Some are more trustworthy than others. They will tell you that it costs fourteen or sixteen hundred dollars to Tripoli. But with a bad guide or bad luck, some pay many times that price, or worse.

In Eritrea, you turn eighteen and go into the army, and you stay in the army for many years, some for the rest of their lives. You work for a few dollars a day—in construction, farming, mining. Those who refuse are sent to prison. There is no other choice. We wanted a better life, a free and normal life. In Europe, we heard, you can live however you want. And so we left Eritrea for Sudan, to Khartoum, then into the Sahara, and into Libya. There were 131 of us. This is the story that we told later, to the police, the journalists, and the courts. One day, a band of armed Somalis came upon us. They forced us into vans and brought us to the town of Sabha, where they locked us up in a house. They made us stand for hours. They tied us upside down and beat on the soles of our feet. They held weapons to our heads and fired bullets into the floor. They drove two of our young women into the desert, raped them, and returned with only one. They poured water over the floor and tried to shock us with a live wire. They succeeded only in burning out the lights.

The Somalis wanted a ransom of $3,300 a head. Two weeks later, most of our families had paid, so they drove us to Tripoli. They took us to the smuggler Ermias. He was dark skinned, around thirty, well fed. He took sixteen hundred dollars from each of us to arrange a boat to Lampedusa. It’s an Italian island about a day off the Libyan coast. Many of us had never seen the sea and we did not know how to swim. We asked if we could pay extra for life jackets; Ermias refused. His men locked us in a warehouse with many others, where we waited through the month of September 2013. On October 2, hours before dawn, they drove us to the shore and ferried us out to a boat, sixty-five feet long. They packed more than five hundred of us onto the bridge and the deck and down in the cabins. The smugglers did not like the look of the boat, so heavy and low in the water, and so old. But they said, “God willing, you will be lucky.”

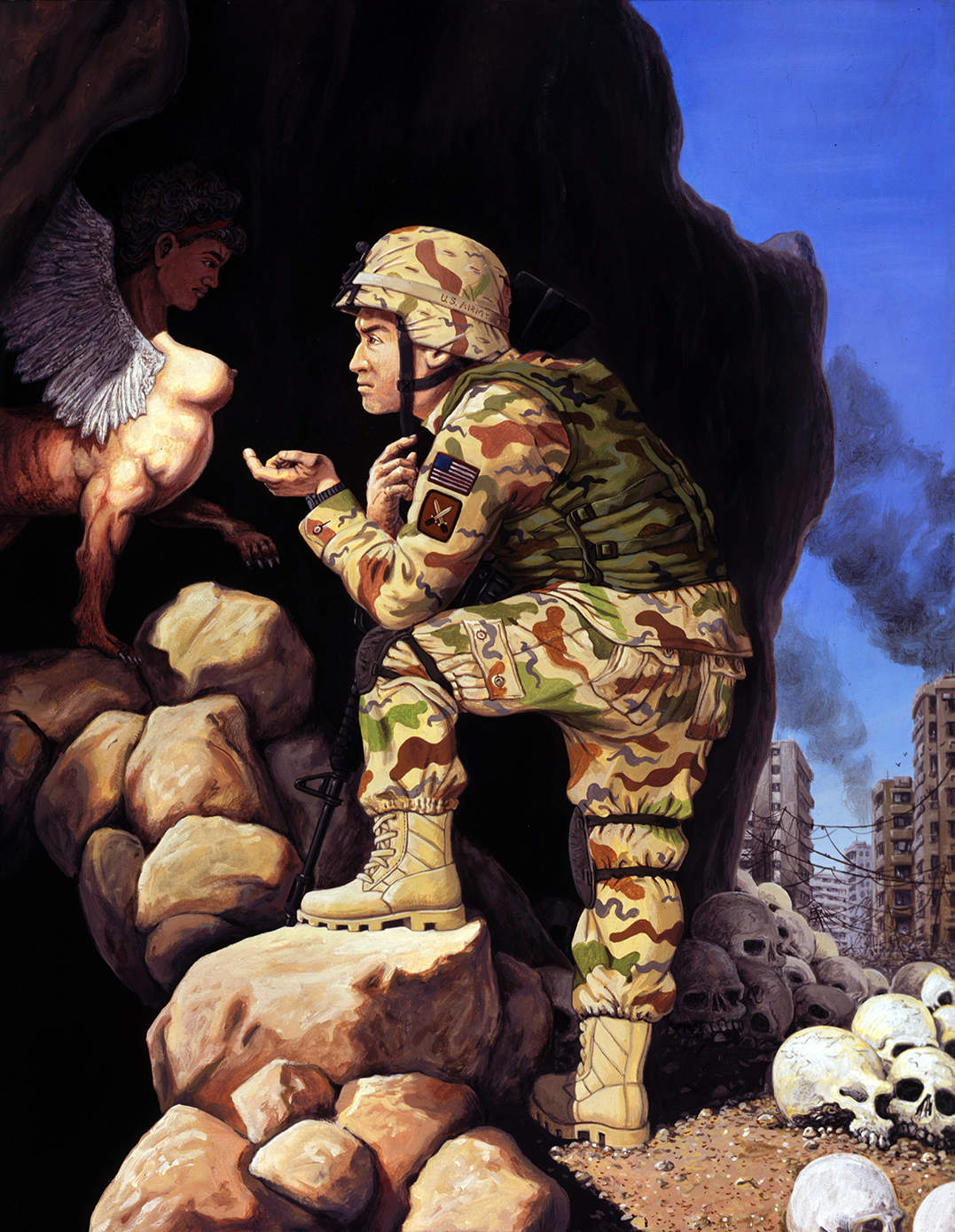

The Riddle of the Sphinx, by Sandow Birk, 2007. Oil on canvas, 34 x 22 inches. © Sandow Birk, courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

The boat set off. We sent the women and children below decks, where they would be more comfortable. Some of us wrote the phone numbers of our families on our clothes. One woman, pinned in a crowded cabin, wrote a number on the wall. It belonged to a Catholic priest, Abba Mussie Zerai—Father Moses. His number is written on the walls of the prisons in Libya. We believed that he could make a rescue boat appear in the middle of the sea.

The captain was a Tunisian man who did not speak our language. He ran the engine through sunset. At three in the morning of October 3, the engine stopped. We were close enough to see the lights on shore. Lampedusa. We waited for the engine to start again. We began to take on water. The captain picked up something and ripped it—was it a bedsheet, a piece of clothing, a blanket? He dipped it in fuel and set it on fire to signal for help. Some people panicked when they saw it burning, and everybody pushed toward the bow. It sank beneath our shifting weight, and the boat turned over and dumped us into the sea.

We said, “Let’s try our luck.” We started swimming. Hands reached out to drag us down. We shook them off. Through the portholes, we could see inside the cabins. Some saw their sons and daughters and wives and chose to drown; some drowned trying to save them. Some called out their names and the names of their villages, so that news of their deaths might be carried to shore.

Around nine am on October 3, Father Mussie Zerai’s telephone began to ring repeatedly. Outside his apartment at the Catholic diocese in Fribourg, Switzerland, the Alps rose above the red-tiled roofs and the Gothic cathedral of the medieval town. The phone calls came from Sweden, Norway, Eritrea, Italy, Sudan, and Lampedusa. A boat traveling from Libya had caught fire and sunk. At least a hundred and eleven people were dead and more than two hundred were missing. It was depressingly familiar news—in the past twenty years, more than twenty thousand immigrants have died on their way to Europe. There would be many more were it not for Zerai, a thirty-nine-year-old Eritrean exile, whose phone number circulates among Europe-bound Africans like a Mediterranean 911. Boats in distress call Zerai by satellite phone, and he writes down their coordinates and passes them on to the Italian authorities to arrange for rescue. When there is no rescue, Zerai takes to Italian TV and radio and mass email to name those whom he believes to be responsible. According to the Italian Coast Guard, Zerai’s calls have helped save five thousand lives.

What struck Zerai on October 3 was the boat’s proximity to land. The drowning of hundreds of people less than a kilometer from Lampedusa seemed like a manifestation of Europe’s approach to African migration—a hardening of its borders coupled with a disturbing indifference to human life. He told an Italian news service that the deaths were “the fruit of a sick relationship between the north and south of the world,” an observation quickly picked up by La Repubblica. That day, Pope Francis called the shipwreck “a disgrace.” Coast Guard divers spent the next week pulling bodies from the hull. Among them, under a hundred and fifty feet of water, was a newborn baby, still attached by the umbilical cord to his mother, who had drowned while giving birth.

Zerai grew up during Eritrea’s long struggle for independence. When he was very young, his home town came under attack. As the walls of his house shook with bomb blasts, his grandmother led him and his siblings to a bunker below ground, knelt with them, and prayed. Later, when a close relative died, she noticed that Zerai was the only family member who did not show any emotion. “And you, what did you put in your belly to make yourself so cold—a stone?” she asked.

Zerai keeps his inner life hidden to this day. “It’s not like I don’t get angry,” Zerai says. “I do. But when I have to have a dialogue with the media or politicians I try to present my reasons with tranquility.”

“He really does have, for lack of a better word, a grace to him,” Luis CdeBaca, the ambassador for the State Department’s anti-human-trafficking office, told me. “You can’t help but be affected by someone who has true calm, true spirituality.”

Zerai works for the Vatican as a parish priest, ministering to the thousands of Eritrean Catholics who live in Switzerland. On his own time, he pursues his migration work under the auspices of Agenzia Habeshia, a charity he named using an ancient word for the Eritrean and Ethiopian peoples. Its phone bills can reach a thousand euros a month. For a while, Zerai was raising tens of thousands of euros to pay his callers’ ransoms, until he realized that this was like trying to smother a fire with kindling. He has set the plight of African migration before Italian ministers, European Union commissioners, and two Popes. In return, he has received many sympathetic words but little change in policy. In fact, the situation is getting worse. The number of immigrants reaching Italian shores in the first three months of 2014 was ten times higher than in the same period last year, the Times reported. Frontex, the European equivalent of the Department of Homeland Security, plans to deploy satellites and drones to guard Europe’s borders, and counsels its security forces on the distinction between directing “returnees” back to Africa and engaging in pushback, a violation of international law. Later, a video surfaced online showing police officers firing rubber bullets into the water near Africans trying to swim around a breakwater protecting a Spanish enclave in Morocco. Fifteen people drowned.

Two weeks after the October 3 shipwreck, Zerai wondered whether there would be any response to the atrocity. “The politicians, they talk, talk, talk. But…,” he said, and shrugged. “Every year, the same thing. After a few months, no one will remember this. Unless us—we continually remember.” Sweat gathered on his forehead, and he dabbed at it with a handkerchief. “It is not possible to accept this type of tragedy as normal,” he said. “This is not a normal accident.”

Untitled (Dunes) near El Centro, California, from The Border Series, by Victoria Sambunaris, 2010. Chromogenic print. © Victoria Sambunaris, courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York.

Lampedusa is a seven-mile flyspeck of limestone and arid soil. Along with nearby Lampione, it is the last of Italy’s footprints on Africa’s continental shelf. Most of its southern shore is forbidding terrain, where the sirocco pushes breakers onto bare crags. In 1843, Ferdinand II claimed Lampedusa for the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies; during the Second World War, the Allies bombed it heavily. After the war, it enjoyed sixty years as a sleepy enclave of fishermen and tourists. In 2000, a wave of xenophobic violence gripped Muammar Qaddafi’s Libya, and displaced immigrants from across Africa began arriving by boat. In 2009, as Italy’s tolerance for new arrivals declined along with its economy, Silvio Berlusconi’s government renamed Lampedusa’s eleven-year-old reception facility the Center for Identification and Expulsion. Today, along with Spanish Morocco, Cyprus, Christmas Island, and Nauru, Lampedusa is a zone of global limbo, where developed nations decide who is most deserving of a new life on the other side of the wall. More than 200,000 people have landed on the island in the past fifteen years. In Libya, human smuggling is called “the Lampa-Lampa business.” During the Arab Spring revolutions of 2011, Italian politicians warned of “a Biblical exodus,” “an invasion” that would bring the country “to its knees.”

Most of the October 3 survivors aspired to official status as “refugees,” meaning that they had fled political persecution and were entitled to protection under international law. Some call the survivors “asylum seekers,” to account for the tenuous nature of their rights. In Italy, they are called clandestini. In Algeria, they are called harraga, Arabic for “those who burn”—some Africans destroy their papers before arrival, to avoid being sent back. The media call them “migrants,” implying that they leave Africa for purely economic reasons. The power to decide who is a refugee and who is a migrant usually lies with interviewers wherever the survivors wind up applying for asylum. The rates at which asylum is granted vary widely. On Lampedusa, new arrivals try to avoid being fingerprinted in Italy so that they can apply for asylum in Norway, Switzerland, and Sweden, which receives more applications from asylum-seeking Eritreans than any other country. The 2006 Schengen Borders Code, which raised the legal walls surrounding Europe while lowering them inside, works in the arrivals’ favor as they continue north.

Relatives will drive thirty hours from Oslo to Sicily, and drive back with their family member, taking advantage of the EU’s open internal borders. Those without someone to call often end up living in baraccopoli—shantytowns—outside Milan and Rome.

Adapted from “The Anchor,” The New Yorker, April 21, 2014. Copyright © 2014 by Mattathias Schwartz. Used with permission of Mattathias Schwartz.

Mattathias Schwartz

From an adapted version of “The Anchor,” a report originally published in The New Yorker. In response to the sinking of this migrant ship, the Italian government launched the Mare Nostrum search-and-rescue operation: in 2014 over 120,000 migrants were picked up by Italian ships. The European Union recently announced it would not assume control of the project, which costs Italy around $12 million a month. For the section of the essay written in the first-person plural, Schwartz relied on interviews with survivors conducted by himself and Italian prosecutors, as well as press reports.