The man who is unrestrained—who has all things in his power as he wills—is free, but he who may be restrained or compelled or hindered or thrown into any condition against his will is a slave. “And who is unrestrained?” He who desires none of those things that belong to others. “And what are those things that belong to others?” Those that are not in our own power, either to have or not to have, or to have them thus or so. Body, therefore, belongs to another, its parts to another, property to another. If, then, you attach yourself to any of these as your own, you will be punished as he deserves who desires what belongs to others.

“And what is all this to freedom?” It lies in nothing else than this—whether you rich people approve or not. “And who affords evidence of this?” Who but yourselves? You who have a powerful master, and live by his motion and nod, and faint away if he does but look sternly upon you who pay your court to old men and old women and say, “I cannot do this or that, it is not in my power.” Speak the truth, then, slave, and do not run away from your masters, nor deny them, nor dare to assert your freedom, when you have so many proofs of your slavery. One might indeed find some excuse for a person compelled by love to do something contrary to his opinion, even when he sees what is best without having resolution enough to follow it, since he is withheld by something overpowering, and in some measure divine. But who can bear with you who are in love with old men and old women, and perform menial offices for them, and bribe them with presents, and wait on them like a slave when they are sick, at the same time wishing they may die and inquiring of the physician whether their distemper be yet mortal? And again, when for these great and venerable magistracies and honors you kiss the hands of the slaves of others, so that you are the slave of those who are not free themselves! And then you walk about in state, a praetor or a consul. Do I not know how you came to be praetor, whence you received the consulship, who gave it to you? I know what a slave is, blinded by what he thinks good fortune.

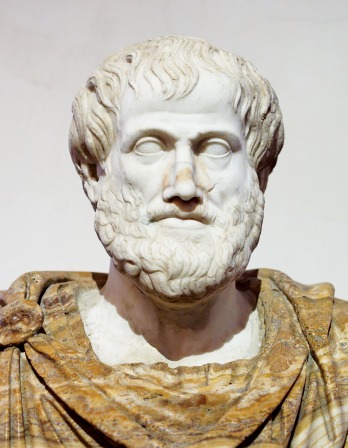

“Are you free yourself, then?” you may ask. By Heaven, I wish and pray for it. But I admit that I cannot yet face my masters. I still pay a regard to my body, and set a great value on keeping it whole—though, for that matter, it is not whole. But I can show you one who was free, so that you may no longer seek an example. Diogenes was free. “How so?” Not because he was of free parents—he was not—but because he was so in himself, because he had cast away all that gives a handle to slavery; nor was there any way of getting at him, nor anywhere to lay hold of him, to enslave him. Everything sat loose on him; everything only just hung on. If you took hold of his possessions, he would rather let them go than follow you for them; if you took hold of his leg, he would let go of his leg; if his body, he would let go of his body; acquaintance, friends, country, just the same. For he knew whence he had them, and from whom, and upon what conditions he received them. But he would never have forsaken his true parents, the gods, and his real country, the universe; nor would he have suffered anyone to be more dutiful and obedient to them than he; nor would anyone have died more readily for his country than he. He never had to inquire about whether he should act for the good of the whole universe; he remembered that everything that exists belongs to that administration and is commanded by its ruler. Accordingly, see what he himself says and writes. “Upon this account,” said he, “O Diogenes, it is in your power to converse as you will with the Persian monarch and with Archidamus, king of the Spartans.” Was it because he was born of free parents? Or was it because they were descended from slaves—that all the Athenians, Spartans, and Corinthians could not converse with them as they pleased, but feared and paid court to them? Why, then, is it in your power, Diogenes? “Because I do not esteem this poor body as my own. Because I want nothing. Because this and nothing else is a law to me.” These were the things that enabled him to be free.

From his Discourses. Born around 55 in Hierapolis, Epictetus was enslaved by one of Nero’s administrators in Rome, where he also may have studied under the Stoic philosopher and senator Musonius Rufus. After receiving his freedom, Epictetus lectured on Stoicism and ethics in Rome, but was forced into exile in 89 following an edict by Domitian banning philosophers from the Italian peninsula. Epictetus fled to Nicopolis, where he established his own school. The historian and philosopher Arrian studied there; scholars believe that his surviving notes, which include this text, are a verbatim record of Epictetus’ teachings.

Back to Issue