Let us make our own mistakes, but let us take comfort in the knowledge that they are our own mistakes.

—Tom Mboya, 1958Escape Mechanism

William and Ellen Craft make a desperate leap for liberty.

Knowing that slaveholders have the privilege of taking their slaves to any part of the country they think proper, it occurred to me that, as my wife was nearly white, I might get her to disguise herself as an invalid gentleman and assume to be my master, while I could attend as his slave, and that in this manner we might effect our escape.

After I thought of the plan, I suggested it to my wife, but at first she shrank from the idea. She thought it was almost impossible for her to assume that disguise and travel a distance of one thousand miles across the slave states. On the other hand, she also thought of her condition. She saw that the laws under which we lived did not recognize her to be a woman, but a mere chattel to be bought and sold, or otherwise dealt with as her owner might see fit. Therefore, the more she contemplated her helpless condition, the more anxious she was to escape from it. She said, “I think it is almost too much for us to undertake. However, I feel that God is on our side, and with his assistance, notwithstanding all the difficulties, we shall be able to succeed. Therefore, if you will purchase the disguise, I will try to carry out the plan.”

But after I concluded to purchase the disguise, I was afraid to go to anyone to ask him to sell me the articles. It is unlawful in Georgia for a white man to trade with slaves without the master’s consent. But notwithstanding this, many persons will sell a slave any article that he can get the money to buy. Not that they sympathize with the slave, but merely because his testimony is not admitted in court against a free white person.

Therefore, with little difficulty, I went to different parts of town, at odd times, and purchased things piece by piece—except the trousers, which my wife found necessary to make—and took them home to the house where she resided. Being a ladies’ maid, and a favorite slave in the family, she was allowed a little room to herself. Among other pieces of furniture which I had made in my overtime was a chest of drawers; so when I took the articles home, she locked them up carefully in these drawers.

When we fancied we had everything ready, the time was fixed for the flight. But we knew it would not do to start off without first getting our master’s consent to be away for a few days. Had we left without this, they would soon have had us back into slavery, and probably we should never have got another fair opportunity of even attempting to escape.

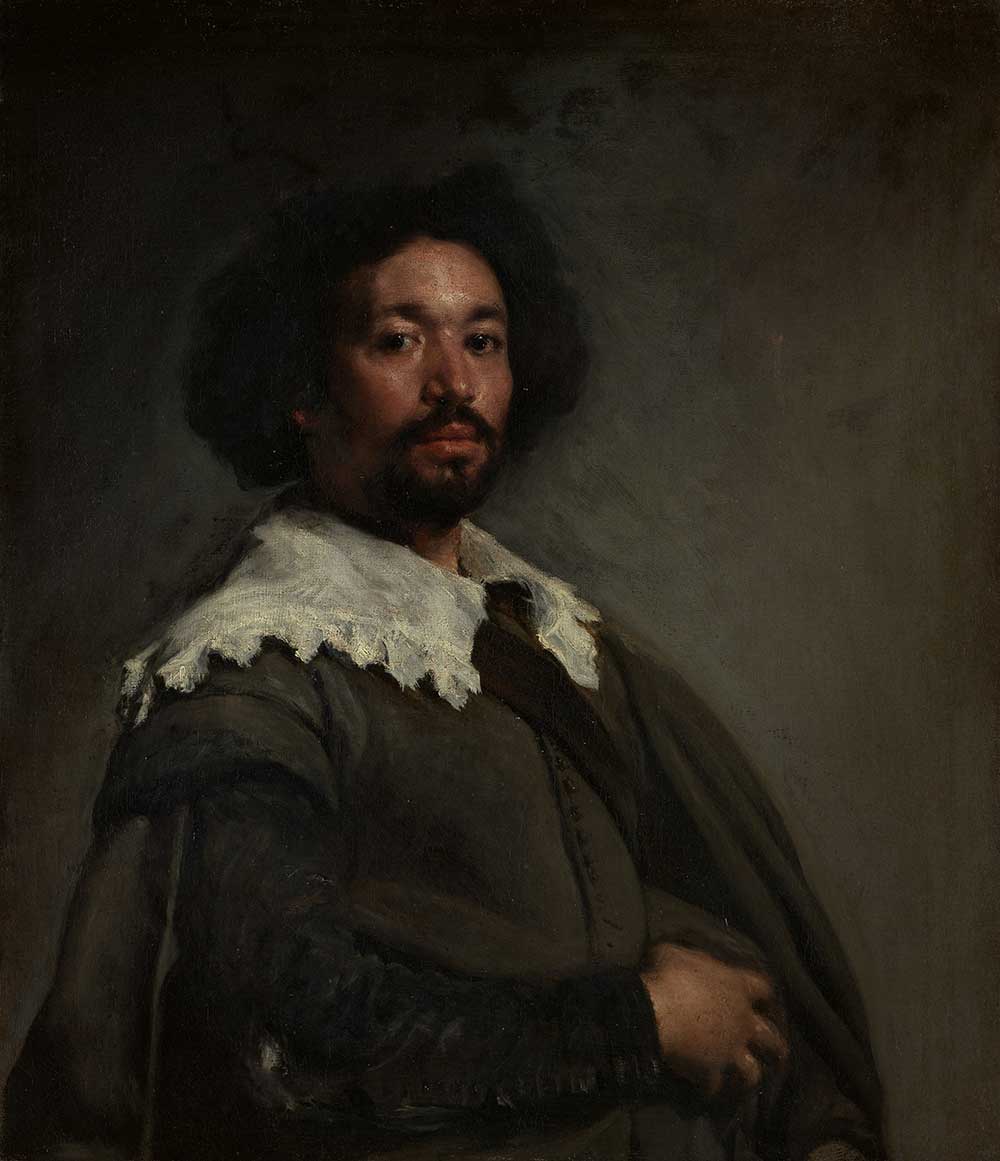

Juan de Pareja, by Diego Velázquez, 1650. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), by exchange, supplemented by gifts from friends of the Museum, 1971.

Some of the best slaveholders will sometimes give their favorite slaves a few days’ holiday at Christmastime. After no little amount of perseverance on my wife’s part, she obtained a pass from her mistress, allowing her to be away for a few days. The cabinetmaker with whom I worked gave me a similar paper, but said that he needed my services very much, and wished me to return as soon as the time granted was up. I thanked him kindly, but somehow I have not been able to make it convenient to return yet.

When I reached my wife’s cottage, she handed me her pass, and I showed mine, but at that time neither of us were able to read them. It is not only unlawful for slaves to be taught to read, but in some states there are heavy penalties attached, such as fines and imprisonment, which will be vigorously enforced upon anyone who is humane enough to violate the so-called law.

At first we were highly delighted at the idea of having gained permission to be absent for a few days. But our spirits drooped within us when the thought flashed across my wife’s mind that it was customary for travelers to register their names in the visitors’ book at hotels, as well as in the clearance or customhouse book at Charleston, South Carolina.

So, while we sat in our little room upon the verge of despair, all at once my wife raised her head, and with a smile upon her face, which was a moment before bathed in tears, said, “I think I have it!” I asked what it was. She said, “I think I can make a poultice and bind up my right hand in a sling, and with propriety ask the officers to register my name for me.” I thought that would do.

It then occurred to her that the smoothness of her face might betray her; so she decided to make another poultice, and put it in a white handkerchief to be worn under the chin, up the cheeks, and to tie over the head. This nearly hid the expression of her countenance, as well as her beardless chin.

My wife, knowing that she would be thrown a good deal into the company of gentlemen, fancied that she could get on better if she had something to go over the eyes. So I went to a shop and bought a pair of green spectacles. This was in the evening.

We sat up all night discussing the plan and making preparations. Just before the time arrived for us to leave in the morning, I cut off my wife’s hair at the back of the head, and got her to dress in the disguise and stand out on the floor. I found that she made a most respectable-looking gentleman.

My wife had no ambition whatever to assume this disguise, and would not have done so had it been possible to have obtained our liberty by simpler means. But we knew it was not customary in the South for ladies to travel with male servants, and therefore it would have been a very difficult task for her to have come off as a free white lady, with me as her slave. In fact, her not being able to write would have made this quite impossible. We knew that no public conveyance would take us or any other slave as a passenger without our master’s consent. This consent could never be obtained to pass into a free state. My wife’s being muffled in the poultices, etc., furnished a plausible excuse for avoiding general conversation, of which most Yankee travelers are passionately fond.

When the time had arrived for us to start, we blew out the lights, knelt down, and prayed to our Heavenly Father mercifully to assist us, as he did his people of old, to escape from cruel bondage. After this we rose and stood for a few moments in breathless silence. We were afraid that someone might have been about the cottage listening and watching our movements. I took my wife by the hand, stepped softly to the door, raised the latch, drew it open, and peeped out. Though there were trees all around the house, the foliage scarcely moved. In fact, everything appeared to be as still as death. I then whispered to my wife, “Come, my dear, let us make a desperate leap for liberty!”

William Craft

From Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. William and Ellen Craft were born into slavery in Georgia. William was apprenticed to a carpenter in Macon, while Ellen, the child of an enslaved woman and a white slaveholder, was sent at the age of eleven to serve as a maid for her half sister. About two years after the Crafts married, they began their escape, with Ellen disguised as an invalid white man; as they approached Charleston by ship, a fellow passenger scolded Ellen for her courtesy toward her “slave,” William. The couple arrived in Philadelphia on Christmas Day in 1848.