Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.

—Benjamin Franklin, 1755Everything Is Better in Siberia

Anton Chekhov pictures a free life.

Two peasant constables—one a stubby, black-bearded individual with such exceptionally short legs that if you looked at him from behind it seemed as though his legs began much lower down than on other people; the other, long, thin, and straight as a stick, with a scanty beard of dark-reddish color—were escorting to the district town a tramp who refused to remember his name. The first was called Andrey Ptaha, the second Nikandr Sapozhnikov.

The man they were escorting did not in the least correspond with the conception everyone has of a tramp. He was a frail little man, weak and sickly, with small, colorless, and extremely indefinite features. His eyebrows were scanty, his expression mild and submissive; he had scarcely a trace of a mustache, though he was over thirty. He walked along timidly, bent forward, with his hands thrust into his sleeves. The collar of his shabby cloth overcoat, which did not look like a peasant’s, was turned up to the very brim of his cap, so that only his little red nose ventured to peep out into the light of day. He spoke in an ingratiating tenor, continually coughing.

Andrey Ptaha was somewhat excited. He kept looking at the tramp and trying to understand how a live, sober man could fail to remember his name.

“You are an Orthodox Christian, aren’t you?” he asked.

“Yes,” the tramp answered mildly.

“Hmm…then you’ve been christened?”

“Why, to be sure! I’m not a Turk. I go to church and to the sacrament, and do not eat meat when it is forbidden. And I observe my religious duties punctually…”

“Well, what are you called, then?”

“Who has any need to know my name?” The tramp sighed, leaning his cheek on his fist. “If I were to tell them my real name and description, they would send me back to hard labor, I know.”

“Why, have you been a convict?”

“I have, dear friend. For four years I went about with my head shaved and fetters on my legs.”

“What for?”

“For murder, my good man! When I was still a boy of eighteen or so, my mama, a nurse, accidentally poured arsenic instead of soda and acid into my master’s glass. There were boxes of all sorts in the storeroom, tons of them; it was easy to make a mistake.”

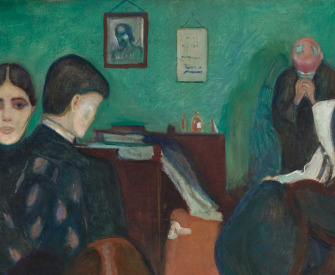

Moses and Pharaoh’s Crown, by Jan Steen, 1670. Mauritshuis, The Hague, acquired with the support of the VriendenLoterij, 2011.

“And why were you sentenced?”

“As an accomplice. I handed the glass to the master. That was always the custom. Mama prepared the soda and I handed it to him. Only I tell you all this as a Christian, brothers, as I would say it before God. Don’t you tell anybody…”

“Oh, nobody’s going to ask us,” said Ptaha. “So you’ve run away from prison, have you?”

“I have, dear friend. Fourteen of us ran away. Some folks—God bless them—ran away and took me with them. Now, you tell me, on your conscience, good man, what reason have I to disclose my name? Let them send me to eastern Siberia,” he said. “I am not afraid of that.”

“Surely that’s no better?”

“It is quite a different thing. In penal servitude you are like a crab in a basket: crowding, crushing, jostling, there’s no room to breathe; it’s downright hell—such hell, may the Queen of Heaven keep us from it! You are a robber and treated like a robber—worse than any dog. You can’t sleep, you can’t eat or even say your prayers. But it’s not like that in a settlement. In a settlement I shall be a member of a commune like other people. The authorities are bound by law to give me my share…yes! They say the land costs nothing, no more than snow; you can take what you like. They will give me farmland and room to build and garden…I shall plow my fields like other people, sow seed. I shall have cattle and stock of all sorts: bees, sheep, and dogs…a Siberian cat, so that rats and mice may not devour my goods. I will put up a house, I shall buy icons. Please God, I’ll get married, I shall have children…”

The tramp muttered and looked, not at his listeners, but away into the distance. Naive as his dreams were, they were uttered in such a genuine and heartfelt tone that it was difficult not to believe in them. The tramp’s little mouth was screwed up in a smile. His eyes and little nose and his whole face were fixed and blank with blissful anticipation of happiness in the distant future. The constables listened and looked at him gravely, not without sympathy. They, too, believed in his dreams.

“I am not afraid of Siberia,” the tramp went on muttering. “Siberia is just as much Russia and has the same God and tsar as here. They are just as Orthodox as you and I. Only there is more freedom there and people are better off. Everything is better there. Take the rivers there, for instance; they are far better than those here. There’s no end of fish, and all sorts of wild fowl. And my greatest pleasure, brothers, is fishing. Give me no bread to eat, but let me sit with a fishhook. Yes, indeed! I fish with a hook and with a wire line, and set creels, and when the ice comes I catch with a net. I am not strong enough to draw up the net, so I shall hire a man for five kopecks. And, Lord, what a pleasure it is. You catch an eelpout or a roach of some sort and are as pleased as if you had met your own brother. And, would you believe it, there’s a special art for every fish: you catch one with live bait, you catch another with a grub, the third with a frog or a grasshopper. One has to understand all that, of course. For example, take the eelpout. It is not a delicate fish—it will take a perch. And a pike loves a gudgeon. The shilishper likes a butterfly. If you fish for a roach in a rapid stream, there is no greater pleasure. You throw the line of seventy feet without lead, with a butterfly or a beetle, so that the bait floats on the surface; you stand in the water without your trousers and let it go with the current, and tug! The roach pulls at it! Only you have got to be artful that he doesn’t carry off the bait, the damned rascal. As soon as he tugs at your line, you must whip it up; it’s no good waiting. It’s wonderful what a lot of fish I’ve caught in my time. When we were running away, the other convicts would sleep in the forest. I could not sleep, but I was off to the river. The rivers there are wide and rapid, the banks are steep—awfully. It’s all slumbering forests on the bank. The trees are so tall that if you look to the top it makes you dizzy. Every pine would be worth ten rubles by the prices here.”

In the overwhelming rush of artistic images of the past and sweet presentiments of happiness in the future, the poor wretch sank into silence, merely moving his lips as though whispering to himself. The vacant, blissful smile never left his lips. The constables were silent. They were pondering with bent heads. In the autumn stillness, when the cold, sullen mist that rises from the earth lies like a weight on the heart, when it stands like a prison wall before the eyes, and reminds man of the limitation of his freedom, it is sweet to think of the broad, rapid rivers, with steep banks wild and luxuriant, of the impenetrable forests, of the boundless steppes. Slowly and quietly the imagination pictures how early in the morning, before the flush of dawn has left the sky, a man makes his way along the steep deserted bank like a tiny speck. The ancient, mastlike pines rise up in terraces on both sides of the torrent, gaze sternly at the free man and murmur menacingly; rocks, huge stones, and thorny bushes bar his way, but he is strong in body and bold in spirit, and has no fear of the pines, nor the stones, nor of his solitude, nor of the reverberating echo that repeats the sound of every footstep he takes. The peasants called up a picture of a free life such as they had never lived; whether they vaguely recalled the images of stories heard long ago or whether notions of a free life had been handed down to them with their flesh and blood from far-off ancestors, God knows.

Anton Chekhov

From “Dreams.” When Chekhov was a teenager, his family moved to Moscow following the bankruptcy of his father, a grocer. Chekhov stayed behind in his hometown and worked as a tutor while finishing high school. After moving to Moscow, he studied medicine and helped support his family through humor writing, publishing his first story in 1880. In 1890 he took a three-month journey through Siberia to the penal colony on Sakhalin Island, financed by a series of newspaper dispatches from the trip; he later collected the reports and offered the proceeds to victims of the famine that struck Russia the following year.