One’s friends are divided into two classes, those one knows because one must and those one knows because one mustn’t.

—Sybil Taylor, 1922Chemistry Test

Dr. Watson meets Sherlock Holmes.

I was standing at the Criterion bar when someone tapped me on the shoulder, and turning around I recognized young Stamford, who had been a dresser under me at Bart’s. The sight of a friendly face in the great wilderness of London is a pleasant thing indeed to a lonely man. In old days Stamford had never been a particular crony of mine, but now I hailed him with enthusiasm, and he, in his turn, appeared to be delighted to see me. In the exuberance of my joy, I asked him to lunch with me at the Holborn, and we started off together in a hansom.

“Whatever have you been doing with yourself, Watson?” he asked in undisguised wonder as we rattled through the crowded London streets. “You are as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut.”

I gave him a short sketch of my adventures and had hardly concluded it by the time that we reached our destination.

“Poor devil!” he said commiseratingly after he had listened to my misfortunes. “What are you up to now?”

“Looking for lodgings,” I answered. “Trying to solve the problem as to whether it is possible to get comfortable rooms at a reasonable price.”

“That’s a strange thing,” remarked my companion. “You are the second man today that has used that expression to me.”

“And who was the first?” I asked.

“A fellow who is working at the chemical laboratory up at the hospital. He was bemoaning himself this morning because he could not get someone to go halves with him in some nice rooms which he had found, and which were too much for his purse.”

“By Jove!” I cried. “If he really wants someone to share the rooms and the expense, I am the very man for him. I should prefer having a partner to being alone.”

Young Stamford looked rather strangely at me over his wineglass.

“You don’t know Sherlock Holmes yet,” he said. “Perhaps you would not care for him as a constant companion.”

“Why, what is there against him?”

“Oh, I didn’t say there was anything against him. He is a little queer in his ideas—an enthusiast in some branches of science. As far as I know, he is a decent fellow enough.”

“A medical student, I suppose?” said I.

“No—I have no idea what he intends to go in for. I believe he is well up in anatomy, and he is a first-class chemist, but as far as I know he has never taken out any systematic medical classes. His studies are very desultory and eccentric, but he has amassed a lot of out-of-the-way knowledge which would astonish his professors.”

“Did you never ask him what he was going in for?” I asked.

“No, he is not a man that it is easy to draw out, though he can be communicative enough when the fancy seizes him.”

“I should like to meet him,” I said. “If I am to lodge with anyone, I should prefer a man of studious and quiet habits. I am not strong enough yet to stand much noise or excitement. I had enough of both in Afghanistan to last me for the remainder of my natural existence. How could I meet this friend of yours?”

“He is sure to be at the laboratory. He either avoids the place for weeks or else he works there from morning to night. If you like, we shall drive around together after luncheon.”

“Certainly,” I answered, and the conversation drifted away into other channels.

We made our way to the hospital after leaving the Holborn. As we spoke we turned down a narrow lane and passed through a small side door, which opened into a wing of the great hospital. It was familiar ground to me, and I needed no guiding as we ascended the bleak stone staircase and made our way down the long corridor, with its vista of whitewashed wall and dun-colored doors. Near the farther end a low, arched passage branched away from it and led to the chemical laboratory.

This was a lofty chamber, lined and littered with countless bottles. Broad, low tables were scattered about, which bristled with retorts, test tubes, and little Bunsen lamps, with their blue, flickering flames. There was only one student in the room, who was bending over a distant table absorbed in his work. At the sound of our steps, he glanced around and sprang to his feet with a cry of pleasure. “I’ve found it! I’ve found it!” he shouted to my companion, running toward us with a test tube in his hand. “I have found a reagent which is precipitated by hemoglobin, and by nothing else.” Had he discovered a gold mine, greater delight could not have shone upon his features.

“Dr. Watson—Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” said Stamford, introducing us.

“How are you?” he said, cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

“How on earth did you know that?” I asked in astonishment.

“Never mind,” said he, chuckling to himself. “The question now is about hemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery of mine?”

“It is interesting, chemically, no doubt,” I answered, “but practically—”

“Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years. Don’t you see that it gives us an infallible test for bloodstains? Come over here, now!” He seized me by the coat sleeve in his eagerness and drew me over to the table at which he had been working. “Let us have some fresh blood,” he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger and drawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. “Now, I add this small quantity of blood to a liter of water. You perceive that the resulting mixture has the appearance of true water. The proportion of blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however, that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction.” As he spoke he threw into the vessel a few white crystals and then added some drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed a dull mahogany color, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottom of the glass jar.

“Ha ha!” he cried, clapping his hands and looking as delighted as a child with a new toy. “What do you think of that?”

“It seems to be a very delicate test,” I remarked.

Marble sarcophagus fragment depicting the death of Meleager, Rome, mid-second century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1920.

“Beautiful! Beautiful! The old guaiacum test was very clumsy and uncertain. So is the microscopic examination for blood corpuscles. The latter is valueless if the stains are a few hours old. Now, this appears to act as well whether the blood is old or new. Had this test been invented, there are hundreds of men now walking the earth who would long ago have paid the penalty of their crimes.”

“Indeed!” I murmured.

“Criminal cases are continually hinging upon that one point. A man is suspected of a crime months perhaps after it has been committed. His linen or clothes are examined, and brownish stains discovered upon them. Are they bloodstains or mud stains or rust stains or fruit stains, or what are they? That is a question which has puzzled many an expert, and why? Because there was no reliable test. Now we have the Sherlock Holmes test, and there will no longer be any difficulty.”

“We came here on business,” said Stamford, sitting down on a three-legged stool and pushing another one in my direction with his foot. “My friend here wants to take diggings, and as you were complaining that you could get no one to go halves with you, I thought that I had better bring you together.”

Sherlock Holmes seemed delighted at the idea of sharing his rooms with me. “I have my eye on a suite in Baker Street,” he said, “which would suit us down to the ground. You don’t mind the smell of strong tobacco, I hope?”

“I always smoke ‘ship’s’ myself,” I answered.

“That’s good enough. I generally have chemicals about and occasionally do experiments. Would that annoy you?”

“By no means.”

“Let me see—what are my other shortcomings? I get in the dumps at times and don’t open my mouth for days on end. You must not think I am sulky when I do that. Just let me alone, and I’ll soon be all right. What have you to confess, now? It’s just as well for two fellows to know the worst of one another before they begin to live together.”

I laughed at this cross-examination. “I keep a bull pup,” I said, “and object to rows, because my nerves are shaken, and I get up at all sorts of ungodly hours, and I am extremely lazy. I have another set of vices when I’m well, but those are the principal ones at present.”

Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies.

—Gore Vidal, 1973“Do you include violin playing in your category of rows?” he asked anxiously.

“It depends on the player,” I answered. “A well-played violin is a treat for the gods; a badly played one—”

“Oh, that’s all right,” he cried with a merry laugh. “I think we may consider the thing as settled—that is, if the rooms are agreeable to you.”

“When shall we see them?”

“Call for me here at noon tomorrow, and we’ll go together and settle everything,” he answered.

“All right—noon exactly,” said I, shaking his hand.

We left him working among his chemicals, and we walked together toward my hotel.

“By the way,” I asked, suddenly, stopping and turning upon Stamford, “how the deuce did he know that I had come from Afghanistan?”

My companion smiled an enigmatical smile. “That’s just his little peculiarity,” he said. “A good many people have wanted to know how he finds things out.”

“Oh, a mystery, is it?” I cried, rubbing my hands. “This is very piquant. I am much obliged to you for bringing us together. ‘The proper study of mankind is man,’ you know.”

“You must study him, then,” Stamford said, as he bade me goodbye. “You’ll find him a knotty problem though. I’ll wager he learns more about you than you about him. Goodbye.”

“Goodbye,” I answered and strolled on to my hotel, considerably interested in my new acquaintance.

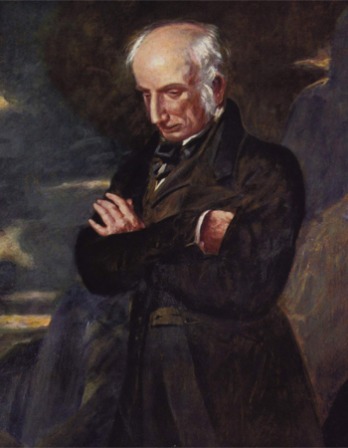

Arthur Conan Doyle

From A Study in Scarlet. While studying medicine in Edinburgh in the early 1880s, Conan Doyle met a professor whose detailed observations and patient diagnoses became the model for Sherlock Holmes. A Study in Scarlet, originally published in 1887 in Beeton’s Christmas Annual, marked the first appearance of Conan Doyle’s best-known character. By 1893 he had written around two dozen Holmes stories. Fed up with the character, he killed off the detective in “The Final Problem,” only to resurrect him eight years later after public outcry.