The world began without man, and it will end without him.

—Claude Lévi-Strauss, 1955New Men and Old

Ivan Turgenev explores the generation gap.

“The motive force behind our actions is that which we recognize to be useful,” pronounced Dr. Bazarov. “At the present time the most useful thing is negation—so we deny—”

“Everything?”

“Everything.”

“How can that be? Not only art, poetry—but also—terrible to say—”

“Everything,” repeated Bazarov with indescribable composure.

The nobleman Pavel Petrovich Kirsanov gaped at him. This he had not expected, and his nephew Arkady actually flushed with pleasure.

“But by your leave,” spoke up Arkady’s father, Nikolai Petrovich, “you deny everything, or to put it more precisely you destroy everything; but when all is said and done it is also necessary to construct.”

“That already goes beyond our task. The first thing is to clear the field.”

“The present state of the people makes it necessary,” added Arkady pompously. “We must bow to that necessity, we have no right to abandon ourselves to the satisfaction of personal egoism.”

This last sentence was evidently not to Bazarov’s liking; it smacked of philosophy, that is of romanticism, for Bazarov designated even philosophy as romanticism; but he did not consider it necessary to refute his young pupil.

“No, no!” exclaimed Pavel Petrovich in a sudden outburst. “I will not believe that you, my fine sirs, really know the Russian people, that you are representatives of their needs, of their aspirations! No, the Russian people are not as you imagine. It is a people who have the deepest reverence for tradition, a patriarchal people who cannot live without faith—”

“I don’t deny it,” Bazarov broke in. “I am even ready to agree that there you are right.”

“But if I am right—”

“Then it still doesn’t prove anything.”

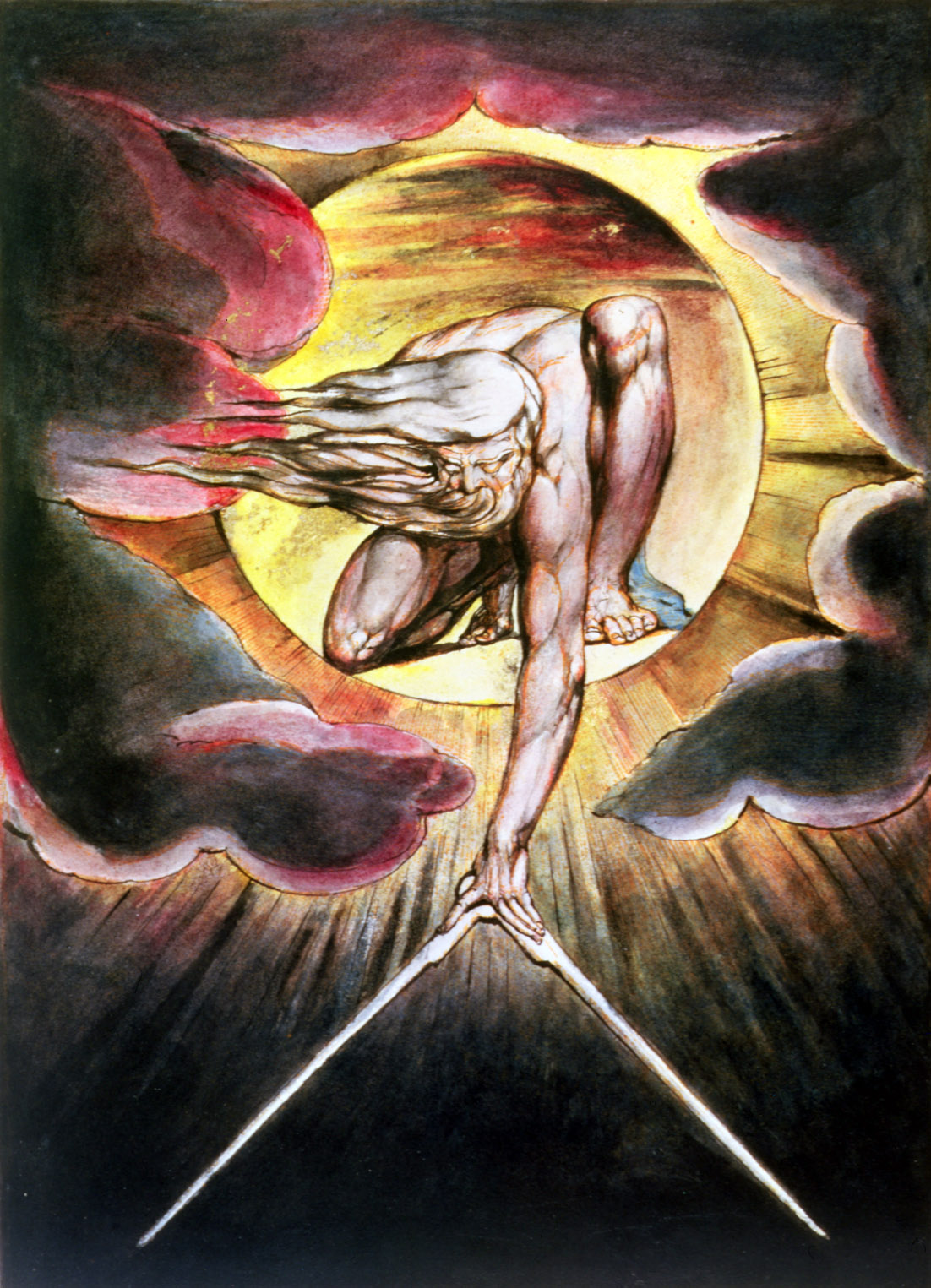

The Ancient of Days, frontispiece for Europe a Prophecy, both by William Blake, 1794. The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

“Exactly, it doesn’t prove anything,” repeated Arkady with the confidence of an experienced chess player who has foreseen an apparently dangerous move on the part of his opponent and has therefore remained quite unruffled.

“What do you mean, ‘It doesn’t prove anything’?” muttered Pavel Petrovich, quite confounded. “Then I suppose you will go against your own people?”

“And even if we would?” cried Bazarov. “The people believe that when there is a clap of thunder it is Elijah the prophet riding about the sky in a chariot. So what? Must I agree with them? And for all that they are Russian, am not I myself a Russian?”

“No! You are not a Russian after all that you have just said. I cannot consider you a Russian.”

“My father walked behind the plow,” Bazarov replied, arrogant with pride. “Ask any one of your peasants in which of us, in you or in me, he would sooner recognize the compatriot. You don’t even know how to talk to him.”

“And you talk to him and despise him at the same time.”

“And why not, if he deserves to be despised? You censure my attitude but how do you know that it has come to me fortuitously, that it isn’t called into being by that very popular spirit which you are so hot to champion?”

“How could that be! We have no use for nihilists.”

“Whether or not they are of any use is not for us to decide. After all, you consider yourself not altogether useless.”

“And have made up our minds to undertake nothing on our own account,” repeated Bazarov grimly. He had suddenly begun to feel annoyed with himself at having so poured out his heart before this “gentleman.”

“And just to sit back and to hurl abuse?”

“And to hurl abuse.”

“And that is called nihilism?”

“And that is called nihilism,” again repeated Bazarov, this time with deliberate insolence.

Pavel Petrovich narrowed his eyes slightly.

“A force which counts no cost,” pronounced Arkady, and drew himself up.

“Unhappy youth!” cried Pavel Petrovich; he was definitely in no condition to contain himself any longer. “If you would only think just what in Russia you were supporting with your banal maxim! No, really, it’s enough to put an angel out of patience! A force! There’s a force in the barbarian Kalmuk and in the Mongol—but what need have we of it? We value our civilization; yes, good sir, yes! We value its fruits. And do not tell me that its fruits are negligible: the last dauber, un barbouilleur, a hack of a pianist who gets five cents an evening for playing at a dance, even these are of more use than you because they are representatives of civilization and not of brute Mongol force! You imagine yourselves to be progressives, and your place is in Kalmuk tents! A force! Well, remember finally, my forceful gentlemen, that there are only four and a half of you in all, and of those who will not permit you to trample underfoot their most sacred beliefs and who will eventually crush you, there are millions!”

“If we are to be crushed then that is our deserts,” said Bazarov. “However, that’s as may be; we are not so few as you think.”

“How is that? Surely, surely you cannot think to gain the sympathy of the whole people?”

“From a penny candle, you know, the whole of Moscow went up in flames,” retorted Bazarov.

“I see, I see! First pride—almost satanic pride—and then cynical mockery. So this, this is the latest craze of youth; this is the doctrine that enslaves the inexperienced hearts of little boys! There, look, one of them is sitting there next to you; why, he almost worships you, just look at him!” (Arkady turned away and frowned.) “And that infection is already widely spread. I have heard that our artists refuse to set foot in Rome. Raphael is considered a fool, for the simple reason that he is, as they say, an authority; and they themselves are weak and impotent to the point of nausea, and their own imagination doesn’t stretch beyond The Maiden at the Fountain, whatever you may say! And the maiden is painted extraordinarily badly. In your opinion they are splendid fellows, am I not right?”

“In my opinion,” corrected Bazarov, “Raphael is not worth a brass farthing, and they are no better than he is.”

“Bravo! Bravo! Listen, Arkady, that is the way modern young men ought to talk! And how shouldn’t they follow you, when you come to think of it. Before, young men had to study; they didn’t want to be known for ignoramuses so they had to work, whether they liked it or not. And now all they have to do is to say ‘Everything in the world is rubbish!’—and it’s all in the bag for them. The young men are delighted. And indeed previously they were just ordinary blockheads, whereas now they have suddenly become nihilists.”

“There now, your famous regard for your own dignity has let you down,” remarked Bazarov phlegmatically, whereas Arkady’s whole figure appeared to bridle with indignation and his eyes took on an angry sparkle. “Our argument has gone too far. It would be better, it seems, to put an end to it. And I will be ready to agree with you,” he added, rising from his chair, “when you are able to show me even one institution in our present way of life which does not call forth the most complete and absolute negation.”

Both friends left the room. The brothers remained alone, and for the first time ventured to look at one another.

“There,” finally began Pavel Petrovich to Nikolai, “there’s the youth of today for you! There they are—our successors!”

Ivan Turgenev

From Fathers and Sons. Born to a philandering father and a wealthy mother with a penchant for beating her sons, Turgenev in his twenties studied classics, history, and the philosophy of G. W. F. Hegel at the University of Berlin, which he attended between 1838 and 1841. He published an obituary of Nikolai Gogol—“Gogol is dead! What Russian heart is not shaken by those three words?”—in 1852, the same year he received wide acclaim for his collection A Sportsman’s Sketches.