“Tell me, Timotheus,” said Harmonides the flute player one day to his teacher, “tell me how I may win distinction in my art. What can I do to make myself known all over Greece? Everything but this you have taught me.

“I have a correct ear, thanks to you, and a smooth, even delivery, and have acquired the light touch so essential to the rendering of rapid measures; rhythmical effect, the adaptation of music to dance, the true character of the different moods—exalted Phrygian, joyous Lydian, majestic Dorian, voluptuous Ionian—all these I have mastered with your assistance. But the prime object of my musical aspirations seems out of my reach: I mean popular esteem, distinction, and notoriety; I would have all eyes turn in my direction, all tongues repeat my name: ‘There goes Harmonides, the great flute player.’ Now when you first came from your home in Boeotia and performed in the Procne and won the prize for your rendering of the Ajax Furens, composed by your namesake, there was not a man who did not know the name of Timotheus of Thebes. In these days you have only to show yourself, and people flock together as birds do at the sight of an owl in daylight. It is for this that I sought to become a flute player; this was to be the reward of all my toil. The skill without the glory I would not take as a gift, not though I should prove to be a Marsyas or an Olympus in disguise. What is the use of a light that is to be hidden under a bushel? Show me then, Timotheus, how I may avail myself of my powers and of my art. I shall be doubly your debtor: not for my skill alone, but for the glory that skill confers.”

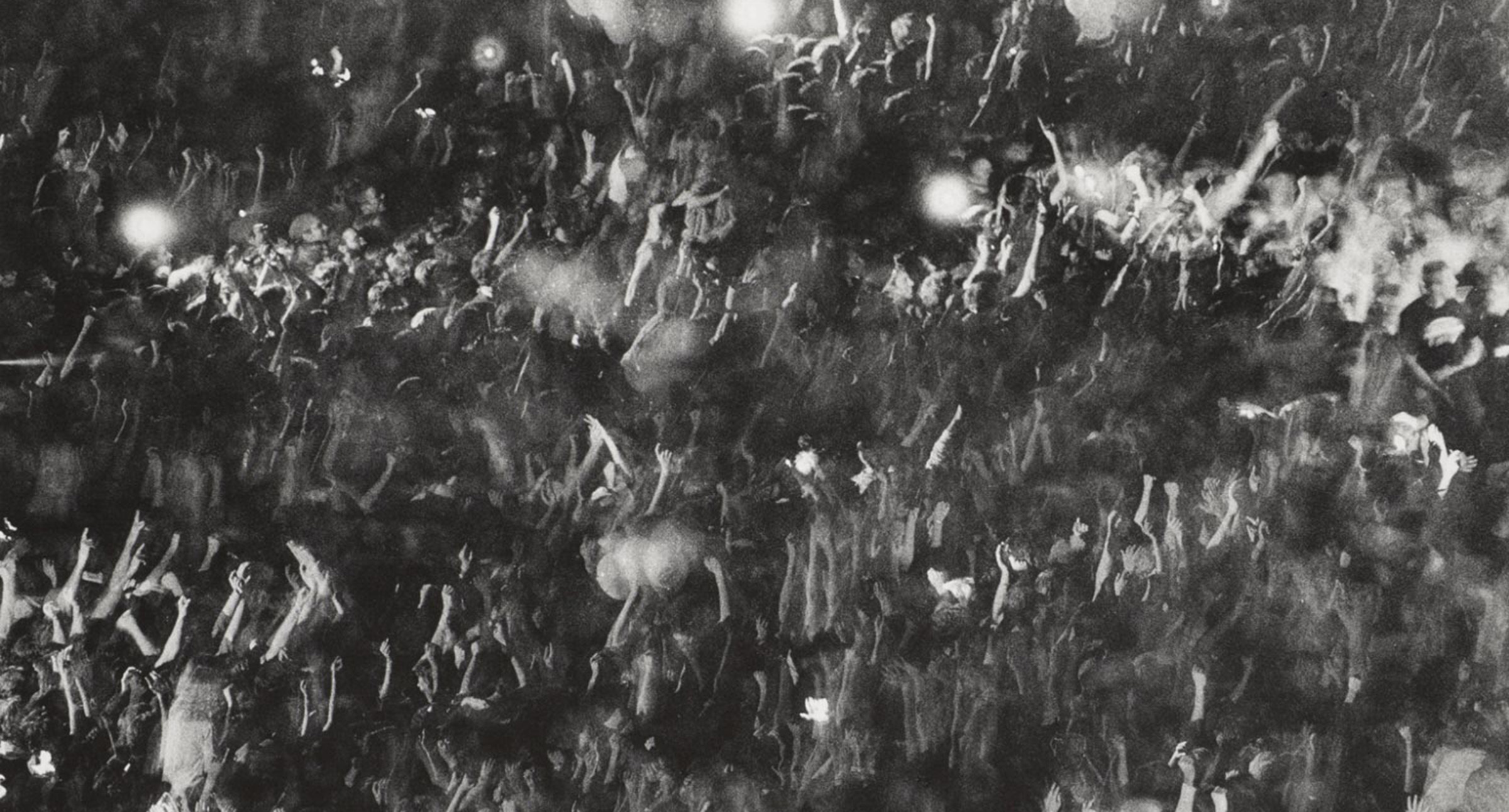

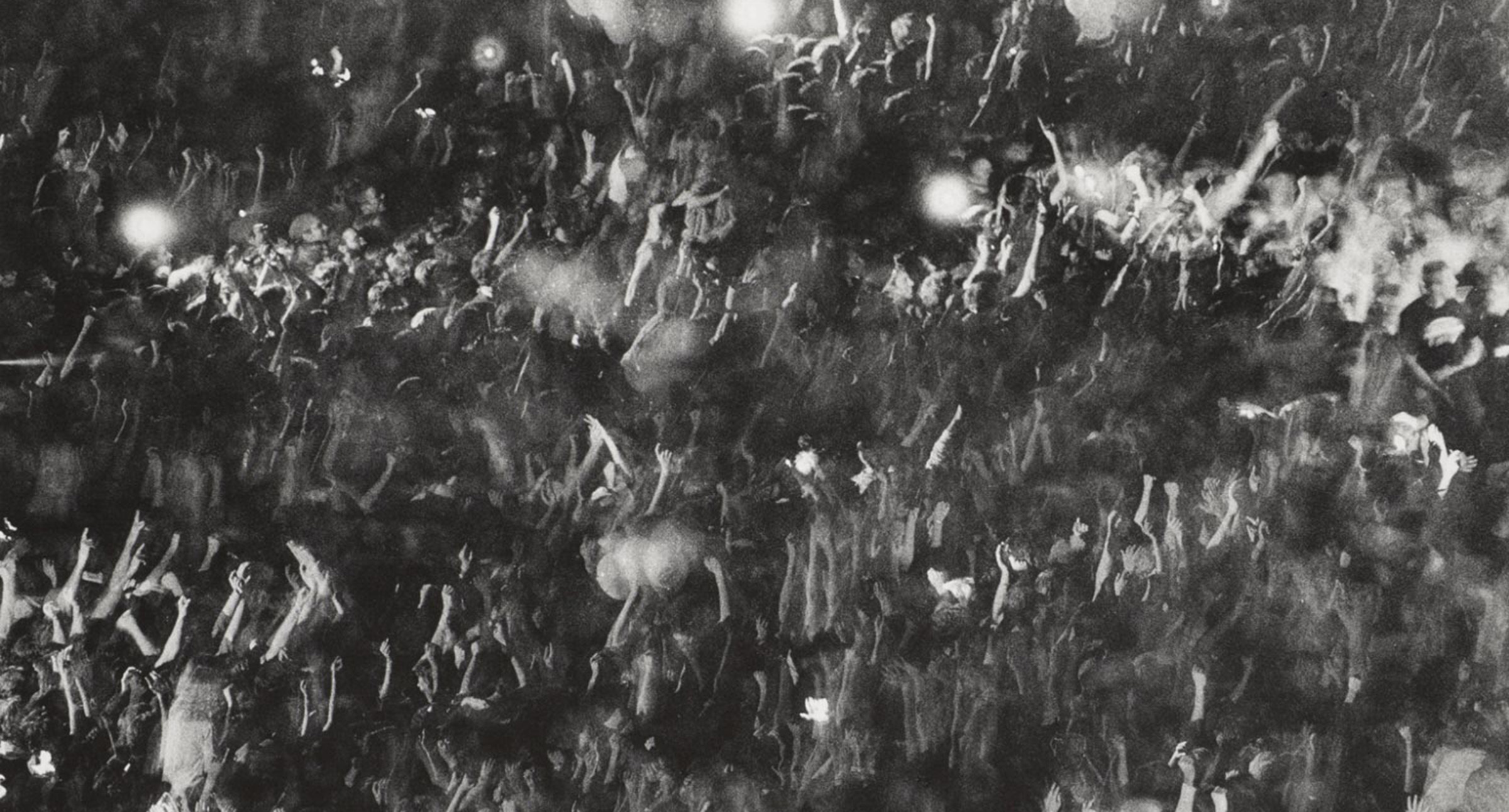

Rolling Stones Concert, New Orleans, by Burk Uzzle, 1982. © Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Lola Downin Peck Fund and with funds contributed by Mr. and Mrs. John Medveckis, Douglas Mellor, Ross Watson, and other donors, 1984.

“Why, really,” says Timotheus, “it is no such easy matter, Harmonides, to become a public character, or to gain the prestige and distinction to which you aspire. If you propose to set about it by performing in public, you will find it a long business and at best will never achieve a universal reputation. Where will you find a theater or circus large enough to admit the whole nation as your audience? But if you would attain your object and become known, take this hint. By all means perform occasionally in the theaters, but do not concern yourself with the public. Here is the royal road to fame: get together a small and select audience of connoisseurs, real experts whose praise, whose blame are equally to be relied on; display your skill to these, and if you can win their approval, you may rest content that in a single hour you have gained a national reputation. I argue thus. If you are known to be an admirable performer by persons who are themselves universally known and admired, what have you to do with public opinion? Public opinion must inevitably follow the opinion of the best judges. The public after all is mainly composed of untutored minds that know not good from bad themselves. When they hear a man praised by the great authorities, they take it for granted that he is not undeserving of praise, and praise him accordingly. It is the same at the games: most of the spectators know enough to clap or hiss, but the judging is done by some five or six persons.”

Harmonides had no time to put this policy into practice. The story goes that in his first public competition, he worked so energetically at his flute that he breathed his last into it and expired then and there, before he could be crowned. His first Dionysian performance was also his last.

From “Harmonides.” The Boeotia-born Timotheus was a master of the aulos, a popular flute-like instrument of ancient Greece. He is often confused with a renowned lyre player also named Timotheus, who lived several centuries earlier; John Dryden’s “Alexander’s Feast” mentions the “breathing flute” and “sounding lyre” of a Timotheus, though neither man played both. Born circa 120, Lucian was apprenticed to a sculptor in his native Samosata and became a successful rhetorician in Italy and Gaul before beginning his writing career in Athens around 160.

Back to Issue