Do that which consists in taking no action, and order will prevail.

—Laozi, 500 BC

Head of Hatshepsut, granite, c. 1479–1458 [small_cap]bc[/small_cap]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1935.

I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to be kept silent.

—First letter of St. Paul to Timothy

Ancient civilization rarely suffered a woman to rule. Historians can find almost no evidence of successful, long-term female leadership from antiquity—not from the Mediterranean nor the Near East, not from Africa, Central Asia, East Asia, nor the New World. In the ancient world, a woman only came to power when crisis descended on her land—a civil war that set brother against husband against cousin, leaving a vacuum of power—or when a dynasty was at its end and all the men in a royal family were dead. Boudicca led her Britons against the aggressions of Rome around 60, but only after that relentless imperial force had all but swallowed up her fiercest kinsmen. A few decades later, Cleopatra used her great wealth and sexuality to tie herself to not one but two of Rome’s greatest generals, just as Egypt was on the brink of provincial servitude to the empire’s insatiable imperial machine. It wasn’t until the development of the modern nation-state that women took on long-lasting mantles of power. After the fall of Rome, the Continent was held in a balance by a delicate web of bloodlines. In an ethnically and linguistically divided Europe when no man could be found to continue a ruling house, finding a female family member was generally preferred to handing the kingdom over to a foreigner.

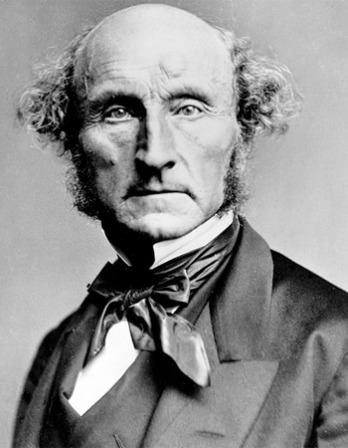

In all antiquity, history records only one woman who successfully calculated a systematic rise to power during a time of peace: Hatshepsut, meaning “the Foremost of Noble Women,” an Egyptian king of the Eighteenth Dynasty who ruled during the fifteenth century bc and negotiated a path from the royal nursery to the very pinnacle of authority. It is not precise to call Hatshepsut a queen, despite the English understanding of the word; once she took the throne, Hatshepsut could only be called a king. In the ancient Egyptian language, the word queen only existed in relation to a man, as the “king’s woman.” Once crowned, Hatshepsut served no man; her husband had been dead some seven years by the time she ascended the throne.

Hatshepsut’s legacy includes her temples, such as the tiered mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri—hieroglyphic texts on the structure were first translated in the nineteenth century, revealing the substance of her reign—and her red-quartzite sanctuary from Karnak. Her tomb in the Valley of the Kings was decorated with spells to the sun as he traversed the hours of night, and her statuary reveals the essential duality of her reign: some show her as a woman, others as a man. Egyptologists remain divided about the identification of her mummy; there are a number of candidates for the valuable corpse that would reveal the wear and tear life dealt her. It is characteristic of ancient Egyptians that they would have forever preserved Hatshepsut’s body but that they recorded so little from her mind. Instead her story must be pieced together from thousands of broken fragments—temples, ritual texts, administrative documents, countless statues and reliefs of herself, her daughter, her stepson, her favored courtiers—a scattered portrait of human life. We don’t know the details of her relationships, if she was loved or reviled. Egyptology reveals the trappings of kingship, but it is very hard to locate the king. Egyptian kings were meant to be living gods on earth, shrouded in idealism and dogma, and those in power played their politics close to the vest—the throne took precedence over any individual and his or her emotions, wants, or desires. Gossip was almost unheard of among the elite and powerful of ancient Egyptian society; public scandal was never recorded into official documents or even unofficial letters. The lives of these mortal gods could only be spoken of in hushed tones.

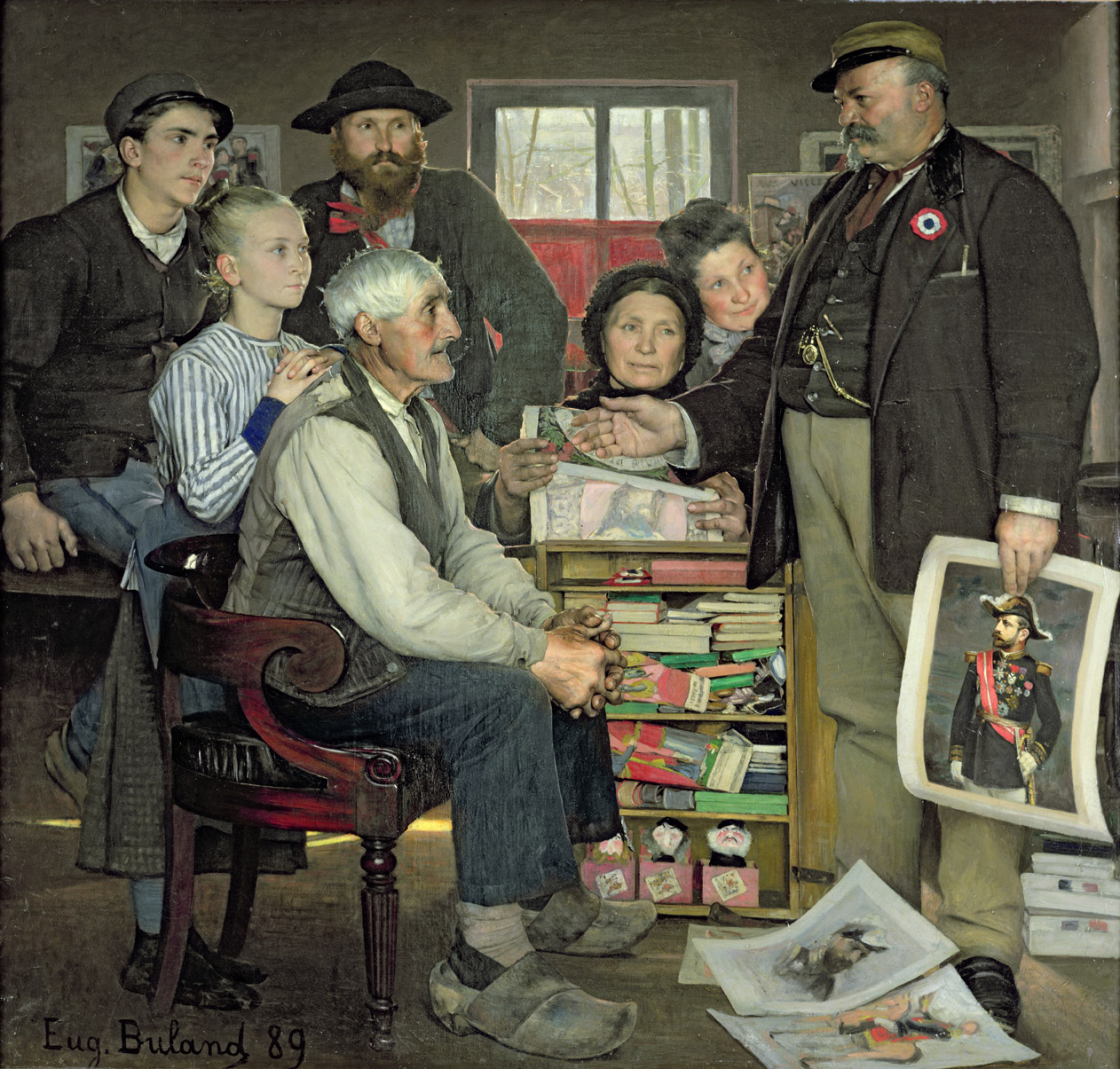

Propaganda, by Eugène Buland, 1889. Musee d'Orsay, Paris.

Hatshepsut was around twenty years old when she methodically consolidated power and catapulted into the highest office in the land. Her youth was unremarkable in a world where tuberculosis, dental abscesses, diarrhea, food poisoning, parasites, cholera, and childbirth might regularly kill a woman; adulthood began early and life ended early (Tutankhamen famously died while still a teenager). Hatshepsut remains the only ancient woman able to claim power when her civilization was at its most robust. During the Eighteenth Dynasty, the Egyptian empire experienced a renaissance—gold poured into the country like water and new building projects were underway, including many of the sprawling temples of Karnak and Luxor so enthralling to tourists today. It was Hatshepsut who began to transform the grandest temple complexes from mud brick to stone, thus promoting each temple’s continued and creeping growth, reign after reign, as future kings made their mark on the sacred landscape with new pylons and gateways, colossal statues and obelisks, sanctuaries and columned halls. Karnak saw structures in sandstone for the first time, and it was here that she added no fewer than two pairs of red granite obelisks, miracles of human ingenuity and energy. (The architecture of her reign was arguably so influential that later New Kingdom pharaohs, including Amenhotep III, Tutankhamen, and Ramses II, were influenced by her choices.) And she achieved this in Egypt, where the very theological tenants of royal power stood against a woman claiming such a position—and where, close to twenty years after her death, the success of her reign could well be the reason that many of her statues, images, as well as her hieroglyphic name were subject to annihilation.

According to Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasty documents, an Egyptian woman was afforded such seemingly modern freedoms as an ability to step beyond the walls of her household, own her own property, and obtain a divorce—yet she remained nothing without connections to her father, husband, or brothers. Documents from Egyptian villages dating from a similar period tell us that a widow was one of the most vulnerable members of society, subject to being thrown out of her own home by a daughter-in-law, but court proceedings also record charges of rape and abuse brought by women against men, and Egyptian women practiced the power to file legal complaints for mistreatment.

A royal woman had less rights than the average Egyptian, it could be argued, since it was impossible to divorce a king, the Golden Horus himself. A woman in the royal household only existed in relation to her king—as king’s daughter, king’s sister, king’s wife, or king’s mother. During the Eighteenth Dynasty, when Hatshepsut lived, royal women could only marry within the boundaries of the palace itself, shuttering dozens of women in a golden prison. Historical evidence from temples, stelae, and statuary indicates that a king’s daughter could only marry the next king—a man who was, more often than not, her own brother or half-brother. Some Egyptian princesses even had the misfortune of extremely long-lived fathers, a circumstance that forced them into marriage with their own fathers, lest they age beyond their childbearing years.

Like any other princess during the Eighteenth Dynasty, Hatshepsut was born into a royal world of social strictures and expectations. She was a king’s daughter, a king’s wife, and a king’s sister—critically, the only royal title she would lack in her lifetime was king’s mother, as she never bore a son. This failing was likely a bitter disappointment for Hatshepsut, but it was also a twist of fate that would pave the way for her inconceivable and serendipitous rise in fortune.

Hatshepsut’s first taste of power came when, just a young girl, she was appointed the god’s wife of Amun. In this hallowed position, she served as a priestess of the greatest importance. If the descriptions of Amun’s rituals of re-creation are to be believed, Hatshepsut was responsible for sexually exciting the god himself, presumably in his statue form. One of her priestess titles was actually “God’s Hand.” If we are to take the agenda of this title literally Hatshepsut was essentially responsible for facilitating the masturbatory act of the god in his holy shrine, instigating a sacred sexual release that allowed for the re-creation of the god, and his entire store of creative potential. As god’s wife, Hatshepsut used her feminine sexuality to enable the god’s continued renewal of the universe itself—it didn’t hurt that the position of god’s wife of Amun came with lands, servants, and palaces. It was a lot of power for a ten-year-old girl to take in.

When Hatshepsut’s father Thutmose I died, she became chief wife to Thutmose II, her own half-brother, at around the age of twelve. The result of this marriage was at least one daughter, a girl named Neferure, and perhaps another daughter who died young. Hatshepsut was denied the son that would have continued her family’s dynasty, and this would define the rest of her life, as Thutmose II may have died as soon as four years later, leaving a very young heir from one of his lesser wives.

Thutmose III, an infant, suddenly sat upon the throne of Egypt, perhaps gnawing on his crook and flail during lengthy religious ceremonies, and was not expected to live long given the high rate of infant mortality. The Egyptians had a solution for such political complications, appointing a regent to oversee the affairs of state until the young king came of age. In Egypt, the king’s regent was normally his own mother, a woman who could have no formal ambitions for herself without harming her own son’s best interests. In the case of Thutmose III, however, the mother seems to have been an inappropriate regent. All evidence suggests that Thutmose III’s mother Isis did not seem to possess the lineage or connections to bear such authority, that she was really nothing more than a pretty concubine. Hatshepsut saw an opportunity: she had been the previous king’s chief wife; she was the highest-born woman in the royal family; she was god’s wife of Amun; she had been trained in the halls of power and in the religious mysteries since her childhood. At around sixteen, she ruled unofficially on behalf of a mere toddler king. Soon she would formally take the throne. For over twenty years she would rule unmolested, but she never ruled alone.

Although we have thousands of temple reliefs, obelisks, pylons, gateways, statues, and inscribed papyri describing this young king, his character and relationship to his aunt Hatshepsut remain shrouded in mystery. Thutmose III was not her child, but it seems that she safeguarded him nonetheless, rearing him for future rule. She transformed herself not into king’s mother, but astoundingly, into a kind of king’s father, a senior king who fostered the education of her royal ward. Granted, for most of her tenure as king, Thutmose III was only a child. But during the last five or six years of her reign, when he had reached his majority, the arrangement became a real partnership. In her temples and stelae, she used her nephew Thutmose III’s regnal year dates. Whenever she depicted herself in the presence of her co-king, she often took the senior position. Yet he was constantly there, lurking in her shadow.

During the next seven or so years as regent, Hatshepsut systematically cemented her path to the kingship. One of her first steps was to gain a throne name, a move which may very well have stunned some officials and nobles, because no Egyptian woman had ever assumed such an honorific without claiming the kingship first. She received the name Maatkare, which is hard to translate but may mean “Truth is the Soul of the sun god Re,” a claim that reinforced her royal power as divinely ordained and offered a guarantee for the continued prosperity that all Egyptian elites were currently enjoying. As regent, Hatshepsut accrued other royal epithets and markers that linked her person to the kingship itself, never so quickly that officials and courtiers would balk, instead waiting patiently to advance another step, until one day around the seventh year after the death of her husband, according to her coronation text, she was formally crowned in the temple of Karnak, in the presence of the god Amun-Re himself.

Egyptian politics were nothing if not religious and conservative; Hatshepsut needed to take her time and exercise patience in order to create an ironclad image of kingship as the divine will of the gods. With only temple reliefs to consult, the reasons for this massive political move remain cloaked. Indeed, without a logical justification for her kingship, many Hatshepsut scholars have deemed her a greedy, scheming shrew who took power that was not rightfully hers, wresting the instruments of rule from a helpless baby. However, since no evidence for this hysterical, ravenous self-indulgence can actually be found in the historical record one way or the other (she did protect the throne for her nephew Thutmose III, after all), some Egyptologists have since explored another logical explanation for a woman holding such high office: she had the help of a man, and it was his idea for her to claim the throne in the first place.

Louis XVI Swearing Loyalty to the Constitution on the Altar of the Homeland, by Nicolas-Guy Brenet, c. 1791. Musée des beaux-arts de Quimper.

One of Hatshepsut’s most loyal supporters during her tenure as regent and then as king, and maybe as early as her time as queen, was a man named Senenmut—a man who rose to become overseer of the entire household of the god Amun-Re, making him chief administrator of what were likely the richest lands and holdings besides those of the crown. Many scholars have concluded that Senenmut must have been her lover, and at the very least he seems to have been the closest person to Hatshepsut beyond her family. Evidence from his tombs and statues also suggests that he never married, which was unusual among Egyptian patricians who hoped to pass down their wealth and influence to their children. Because Senenmut’s parents were of lower birth and had little to no influence at court, this man’s political existence depended on his relationship with Hatshepsut and her daughter Neferure. They seem to have been mutually dependent on the other, she using his reliance on her for her own gain, he using her lack of trust in others for his own advancement. Whether they ever consummated this successful working relationship is a debate left to Egyptologists.

Hatshepsut’s sexual life is almost completely shielded from our eyes. We know that she was sexually active at one point in her life and that she bore at least one, and possibly two, daughters to her husband, Thutmose II. After his death, there is no mention of subsequent children, but a lack of babies does not mean a lack of sex, particularly for a powerful woman in command of men. Hatshepsut was a young woman, and it is certainly within the realm of possibility that she acted as most humans of that age do—engaging in sexual activity and falling in love, having crushes and flirting. Even though no economic records or graffiti or letters record any of Hatshepsut’s conquests, did she have to visit the palace doctor to weigh her options? While Egyptian medical texts describe herbal prescriptions for both birth control and abortions, there are no known private documents that mention their use by any particular woman. We know nothing about this aspect of her life except that Hatshepsut would not have included a romantic partner in any of her formal activities as king. Her official cohorts were family members intimately connected to her kingship: her junior king Thutmose III and her daughter Neferure, who fulfilled the functions of both queen and priestess. A formally recognized male partner would have compromised her theological position as king of Upper and Lower Egypt and as the offspring of Re. From the very beginning Hatshepsut must have known that her femininity was a problem, and step by step she had to erase the most obvious aspects of her womanly self.

Egyptian kingship was inherently masculine; religious texts clearly link masculine sexual potency with transformation. The god Atum created himself from nothing by means of a sacred act of sex between his own hand and phallus. Osiris was said to return from the dead through the same act of self-gratification. Re was believed to impregnate his own mother with his future self at the moment of his death in the western horizon. One of Amun-Re’s titles was “Bull of his Mother,” evoking the potential of this god to create himself before he had even existed, and the Egyptian king was believed to be the son of Re and thus the inheritor of these sacred sexual abilities. A king’s capacity to create offspring through his sexuality wasn’t just a guarantee of the continued existence of the kingship, it was a mythical cycle as potent as the circuit of the sun, the seasons of the year and the annual flooding of the Nile. The Egyptian king was his father before him and his son after him simultaneously. His royal essence was passed down in an unbroken line of sacred dynastic succession. Given that the king on earth was nothing less than the human embodiment of the creator god’s potentiality, Hatshepsut must have been all too aware that her rule posed a serious existential problem: she could not populate a harem, spread her seed, and fill the royal nurseries with potential heirs; she could not claim to be the strong bull of Egypt.

As she aged, Hatshepsut embarked upon a premeditated and careful ideological transformation of her feminine self. Early statuary and imagery show her as a woman in a dress, breasts clearly visible, but also wearing masculine kingly regalia. One statue depicts her wearing not a dress but only a kilt to cover her lower body. Her naked upper body betrays the narrow shoulders and feminine breasts that were a natural characteristic of her sex, and the statue is shocking in its suggestion that Hatshepsut may have actually taken part in religious rituals in this state of undress, breasts clearly visible for all to see.

Yet most images of her after her coronation show her as a man—wide shoulders, trim hips, and no hint of breasts. But throughout these visual changes, she retained her feminine name Hatshepsut, “Foremost of Noble Women,” as well as the feminine pronouns “she” and “her” in many of the concomitant Egyptian texts. It’s as if she knew that those who could read—educated elites and courtiers—knew full well that she was a woman, so why bother hiding it from them, or, for that matter, from the gods? In the ancient world, a woman in her thirties was approaching old age. Fittingly, the loss of Hatshepsut’s youthful beauty and sexual attraction to men coincided with her construction of a masculinized female king. By the time of her death, when her mature woman’s body was placed into a king’s sarcophagus in the hidden crevices of the Valley of the Kings, her mortuary temple included dozens of statues of her as a muscular, masculine ruler, presenting offerings to the god.

My people and I have come to an agreement that satisfies us both. They are to say what they please, and I am to do what I please.

—Frederick the Great, 1770In many ways Hatshepsut’s unconventional kingship was an exercise in conformity. She fit herself into the patterns of kingship with which she had grown up, at least those in which a woman could conceivably participate. Like any successful king, she waged imperial warfare to bring the spoils of war to Amun’s temple; she ruthlessly exploited the population of Nubia to enrich her gods and her people with a metal that evoked the flesh of the sun god; she participated in the respected system of co-regency in which an elder king fostered a junior king in a divinely inspired partnership, thus protecting the future kingship of Thutmose III; she created a masculine identity for herself so that she could perform and participate in religious rituals that demanded such a persona of herself; she constructed temples and obelisks according to accepted traditions; she left behind more stone temples and monuments than any previous king of the New Kingdom; she made no revolutionary breaks with tradition, but instead attempted to link herself with the unending line of masculine kings who had come before her.

Perhaps the removal of her names and images from Egypt’s monuments some twenty years after her death is an indicator of her success as king, because even after death she could threaten her successors, but that is perhaps wishful thinking. The Egyptian system of political-religious power simply continued to work for the benefit of male dynasty. Hatshepsut’s kingship was a fantastic and unbelievable aberration. Ancient civilization didn’t suffer a woman to rule, no matter how much she conformed to religious and political systems; no matter how much she ascribed her rule to the will of the gods themselves; no matter how much she changed her womanly form into masculine ideals. Her rule was perceived as a complication by later rulers—praiseworthy yet blameworthy, conservatively pious and yet audaciously innovative—nuances that the two kings who ruled after her reconciled only through the destruction of her public monuments.