I never know quite when I’m not writing. Sometimes my wife comes up to me at a party and says, Dammit, Thurber, stop writing. She usually catches me in the middle of a paragraph. Or my daughter will look up from the dinner table and ask, Is he sick? No, my wife says, he’s writing something.

—James Thurber, 1955Lady in a Veil

Despite being told that art is somehow sacred, it’s better to take a naive delight in the thing itself.

By Lewis H. Lapham

Modern Rome, by Giovanni Paolo Panini, 1757. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gwynne Andrews Fund, 1952.

Art! Who comprehends her? With whom can one consult concerning this great goddess?

—Ludwig van Beethoven

To the first question I have no more of an answer than did Beethoven; as for the second, I consult his piano sonatas, a few of which I once was able to play and in the listening to most of which I discover the enlarged sense and state of being that is the presence of the great goddess. The liftings of her veil in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly concern the uses of art as a medium of exchange, the gift in the hand of its creator alive in the mind of its beholder, converting the private to a public good and thereby adding it to the common store of human energy and hope. The embodiment of the spirit in the flesh to which Tolstoy refers as “a means of communion among people … the capacity of people to be infected by the feelings of other people,” by “feelings, the most diverse, very strong and very weak, very significant and very worthless, very bad and very good.” The spread of the infection rejoiced in by Montaigne, who approached his library in search of an escape from the “tedious idleness” and “disagreeable company” in the prison of the self.

The supposition that art is a gift as opposed to a collectible, something that doesn’t try to sell you anything, runs counter to our contemporary notions of what constitutes a meaningful exchange. If I couldn’t deduce the fact from the price paid for Damien Hirst’s shark afloat in formaldehyde, I was reminded of it some months ago when asked by the 92nd Street Y in Manhattan to mount a discussion about the role of the artist in postmodern American society. The auditorium serves as a trendsetting display case for the city’s high-end cultural merchandise, and the booking agent requested participants—an author, an actress, possibly a musician or a film director—deserving the cost of ad space in the New York Times. I offered the names of several individuals apt to say something of interest on the topic, but none was deemed fit to print. What the participants said or didn’t say was of no consequence. What was important was the magnitude of their celebrity, and the names on my list were rated as low-burning flames unable to convene a gathering of moths. I can’t say I was surprised. To a young writer who had asked for advice about advancing his literary career in the late 1960s, Gore Vidal had provided clear directions to Mt. Parnassus. “Never miss a chance,” he said, “to have sex or appear on television.” Forty years have passed, and these days a young writer applying for consultation with the muses assembled on East Ninety-second Street probably would be better advised to combine the two initiatives.

The record shows that throughout most of the country’s history the circumstances haven’t been much different. John Adams associated the arts with “despotism” and “superstition.” “To America,” said Benjamin Franklin, “one schoolmaster is worth a dozen poets, and the invention of a machine or the improvement of an implement is of more importance than a masterpiece of Raphael.” The Nobel Prizes awarded almost every year to American chemists and economists suggest that the inspired play of the American mind takes place in the theater of the sciences and the concert halls of money.

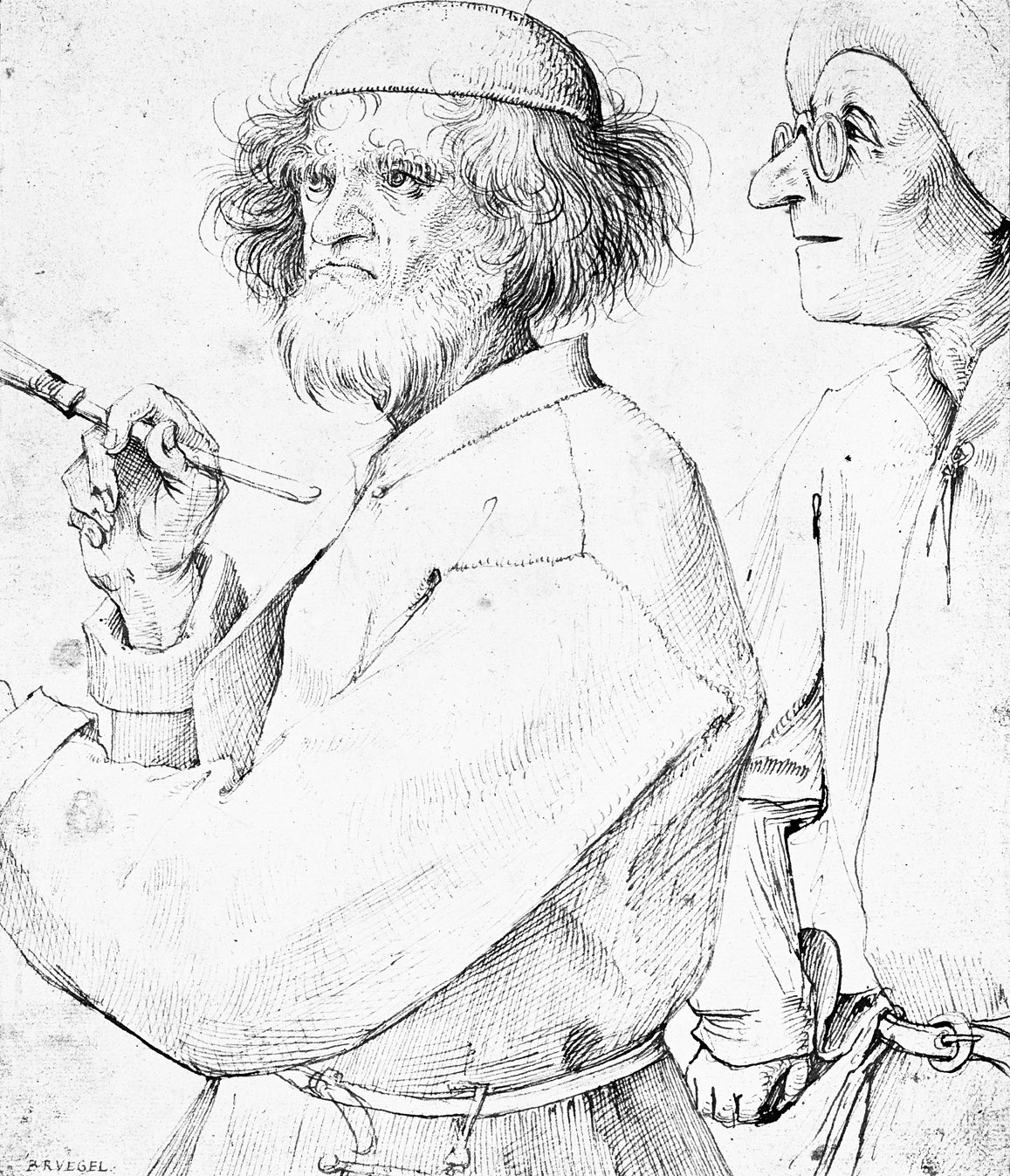

Painter and his Patron, by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, c. 1565. The Albertina, Vienna, Austria.

My own great expectation of the arts is an accident of birth, in San Francisco in 1935 in a household filled with books. At the age of six, attracted to the Rockwell Kent illustrations in the Lakeside Press edition of

Moby Dick, I persuaded my mother to read the novel aloud by agreeing that if on any subsequent evening I couldn’t remember where it was that the story had been left off—Queequeg sharpening his harpoon, Ahab steadfast in his quest for vengeance—she would close the book and move on to the travails of Peter Rabbit. The reading took the better part of the same year in which the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and by the time we’d come to the end of it—the Pequod sunk, Ishmael tangled in the shroud of the Pacific Ocean—I could imagine, sometimes almost see, if not the great goddess on the page, the looming of the great white whale in San Francisco Bay.

My early meeting with Melville’s prose dates the formulation of my idea of what was to be construed as literature. Both at home and at school in the 1940s, I kept company with authors in whose writing I could hear the music in the words, in the novels of Joseph Conrad, Edward Gibbon’s history of the Roman Empire, the poems of Coleridge and Kipling. I’m still subject to the predisposition. On first opening a book that I’m not obliged to read for professional reasons, I’m content to let it pass by unless I can hear some sort of melodic line, even if the author offers to name the man who shot Jack Kennedy. With authors of great reputation, I blame myself for whatever fault can be found, and after a decent interval of years I return to the book in question in the hope that I’ve learned to hear what is being said. When I was twenty I didn’t know how to read Ford Madox Ford or

George Eliot. By the time I was fifty I no longer could read J.D. Salinger or Ernest Hemingway. I’ve yet to learn how to read Finnegans Wake.

Regarding myself as neither art historian nor literary critic, I escape the chore of having to discern zeitgeists and deconstruct paradigms. At liberty to indulge my enthusiasms without apology or embarrassment, I’m free to take as much pleasure from the novels of Raymond Chandler and John le Carré as from the poetry of Wallace Stevens. Because I look for the value of the human currency (“very strong and very weak … very bad and very good”), I don’t much care whether an author chooses for her mise en scène the court of Henry VIII or the roof of a Harlem tenement, whether the artist draws a bandit on the beach at Yokohama or paints an angel on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. In Goya’s etchings of the Napoleonic Wars, I discover an enlarged state and sense of being of the same order as the one met with in the second movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no. 27 or in the sequence of images on exhibition in Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts.” “Feelings, the most diverse,” follow from the awakening of more than one mind to the excitement of simultaneous discovery, which is the means of communion that distinguishes the making of a work of art from the passive and singleminded consumption of a camera angle or an applause track.

To the generation coming of age in the ’40s and ’50s, the distinction was important, maybe even bearing on what was to become of the American future. It was a generation infected with the idea that the arts were serious business, sharing with the late Walker Percy his novelist’s belief that all fiction can be used as an instrument of exploration and discovery, that “the novelist or poet in the future might be able to go further, to discover or rediscover … how it is with man himself, who he is, and how it is between him and other men.” During the years of the Eisenhower administration, the portraits of novelists decorated the covers of Time magazine, the views of Saul Bellow and Norman Mailer accorded the deference now placed at the feet of Warren Buffett. New plays on Broadway from Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams were as eagerly received as the musicals by Rodgers and Hammerstein. Under the aegis of the Congress of Cultural Freedom, the CIA was deploying American art as a Cold War weapon of mass instruction. Although the Allies had won the war against Hitler (won it in the name of democratic freedom and Western civilization), they appeared to be losing the peace to Stalin and the systems of totalitarian repression, and what was afoot in the 1950s was a contest for the good opinion of mankind. The communist agitprop on offer in Europe in 1947 pictured the United States as a materialist wasteland inhabited by gum-chewing shoe salesmen, lynchers of negroes ignorant of the works of Gramsci and Lukács.

The CIA undertook to suppress the rumors, directing the tactical movement of art exhibits to Venice, music festivals to Rome. Not satisfied with the wholesale distributions of wholesome texts, the agency pressed forward into the no man’s land of the avant-garde, seeking to show its prospective friends in Bremerhaven and Marseilles that American art was something more than a provincial reflection of European decadence. No, by God, America was a great country, as rich in artists as it was in steel or corn, and here to prove it on the wall in Paris is the Abstract Expressionism of Jackson Pollock—a real American from Cody, Wyoming, not a Hungarian refugee or a Princeton homosexual; virility incarnate, reckless and heavy-drinking, a fountain of acrylic orgasm; just the sort of fellow to represent the virtues of free enterprise, and whose paintings, nonfigurative and incoherent, embodied the antithesis of Soviet socialist realism. The aesthetic stamped with the seals of government approval matched the one embraced by the Beat poets howling in the California wilderness, marking out the road into an ecstatic future unregulated by death and taxes.

As trickled down to the undergraduate elements of the avant-garde at Yale College in the 1950s, questions about the uses of art (its place in society, its promise of a career) resolved into a “pandemonium” of words like those recorded by Roberto Bolaño and described by Stefan Zweig as a “collective, eager, competitive curiosity” translated into vivid statements of noble principle and passionate objection. Usually I found myself on the wrong side of the critique, in some quarters regarded as an obsolete romantic, in others as a trivial bourgeois. Introduced to the modernist doctrines of alienation and despair, I took the notes but didn’t learn the lesson. The Bauhaus architecture I thought better suited for a barracks or a penitentiary; in the paintings of Mondrian and Kandinsky I could recognize little else except the surface of a decorative design. Nor in the works of Berg and Shostakovich could I identify the sound that from the seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century composers I’d learned to recognize as music. The apparatchiks in the English department employed the techniques remarked upon by Billy Collins—“tie the poem to a chair with rope/and torture a confession out of it,” beat it with a hose “to find out what it really means.” I was less interested in what it really meant than in A.E. Housman’s definition of poetry as that which raises the hair on the chin while shaving. Despite four years of being told that art was somehow sacred, divorced from all sakes other than its own, I never learned to prefer the comprehension of the theory of the thing to a naive delight in the thing itself.

But in what was then the spirit of the times, the side of the argument on which anybody came down, against Haydn and for Stravinsky, with the early or the late Picasso, mattered less than the shared belief among all the voices in the room that it was art and literature that were to be looked to for the light on the far and fair horizon. The certainty was in line with the generous idealisms expressed in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights as well as with the intent to furnish the newly emergent American empire with the trophy of a civilization. America’s victories in World War II had established its military and economic predominance; in the 1950s it was thought that a determined courting of the lady in the veil would bring forth works of genius of a match with the arriviste hegemon’s spiritual and moral grace. Other empires had done so, most notably Periclean Athens, Elizabethan England, France during the reign of Louis XIV. Surely the United States could produce something equally impressive. Was not America richer than any other country known to history? Were not its weapons more terrible, its virtues more abundant? How then could its painting not be more luminous, its literature more profound, its music more sublime?

The fond hopes and great expectations didn’t survive the epistemological shift during the 1960s to the political and commercial sets of reference. The passionate objections and statements of noble principle were transposed into the key signatures of the Civil Rights movement and the opposition to the Vietnam War, proofs of the higher consciousness spray-painted on T-shirts, hoisted on the signs of protest. The locus of advanced artistic opinion moved from the Greenwich Village bars to the pages of Women’s Wear Daily; Andy Warhol discovered a market for portraits of Campbell’s Soup cans, and the several forms of expression previously known as the “lively arts” were melted down into the alloy of the “media.” By the time President Ronald Reagan danced onto the White House stage in 1981, politics was fashion, news was entertainment, celebrity was art, literature a regional dialect spoken only in the universities. Two texts in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly give dates for the change in mood and tone. Barbara Rose names the evening of October 18, 1973, the art world ending “not with a whimper, but with a bid” at Sotheby Parke Bernet, the high prices paid at auction for works by Willem de Kooning and Jasper Johns testifying not to the value of the art but to the vanity of the buyers seeking to transform themselves into “living sculpture.”

Jamie James suggests November 1972, the month that Ezra Pound died, as the end of poetry as conceived by Goethe, the global language that is “the universal possession of mankind, revealing itself everywhere and at all times in hundreds and hundreds of men.”

It isn’t that the country now lacks for painters painting pictures or poets writing poems; nor is it to say that stores of human energy and hope aren’t to be found in the novels of Elmore Leonard or the songs of Bruce Springsteen. It is to say that with the dawn of Reagan’s bright new morning in America, the notion of art as the way into a redemptive future had withered on the vine. Once again, as had been customary throughout most of the country’s history, art was seen as an embodiment of the good, the true, and the beautiful only to the extent that it could be exchanged for money.

If in the 1950s the young and aspiring writer hoped to become a novelist or a playwright, thirty years later the ambition had been replaced with the thought of becoming a critic, a journalist, or a policy intellectual, possibly a television talking head. Instead of addressing George Orwell’s concern for the safety of the English language, the conversations revolved around the names of Hollywood agents and the grooming of résumés fit for the favor of a foundation grant. The generation of writers weaned on Cold War propaganda and CIA subsidy adopted the trade craft of literary realpolitik to variant doctrines of political correctness, the combatants on both the left and right construing culture as ideology, the frivolous adjective modifying the sober noun—cultural identity, cultural diversity, cultural policy-objective. The love of language once inherent in a distinctive literary style not only fell out of favor but was placed under suspicion as an un-American activity. Among New York editors it was assumed that a writer who clogged the data streams with arresting turns of phrase could not be trusted to impart the truth.

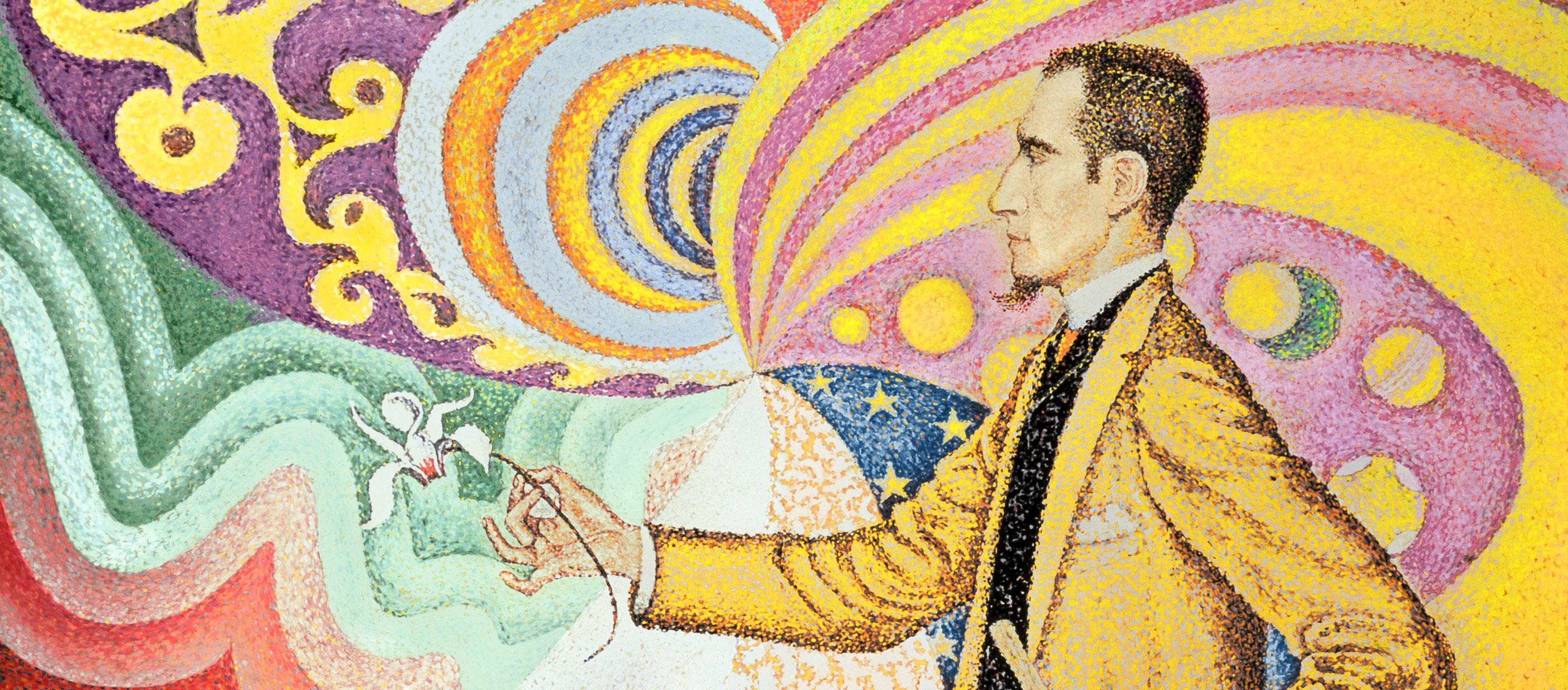

Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones and Tints, Portrait of Félix Fénéon in 1890, by Paul Signac, 1890. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York.

At the downtown exhibitions of conceptual art in the early ’90s, the gallery walls served as bulletin boards on which to post a syllabus of moral lessons imbedded in twisted steel and fluorescent neon light. Ugly was a show of virtue, and so was the lack of talent, the bombast recurring in the explanatory notes (“imperialism,” “otherness,” “void,” “difference”) pointing as garishly as road signs to the injustices of gender, race, wealth, and social class. It was not enough merely to look at a battered rubber woman or a pair of gold-plated tennis sneakers. What was important was the theory of the thing, not the thing itself, the knowing that beauty was reactionary and that the artists labeling the merchandise had come to think of history as a “dysfunctional idea.” The message brought with it the great good news that the arts, when not otherwise employed as political agitprop or commercial advertising, offered refuge from a dysfunctional grasp of reality with welcome escapes into the nearest mirror. Novels that in the 1950s set out to discover how it is with man in the company of other men gave way in the 1980s to the writing of memoirs intent upon discovering that when one really had a chance to think about it, the world and all its troubles were really all about me. The authors who would be king placed stylish gestures of self-loathing on the altar of self-promotion.

The United States Census Bureau now counts almost two million Americans working in the arts, many of them under the impression that the occupation designates them a law unto themselves, granted the equivalent of the “moral waivers” that the U.S. Army bestows on those of its sorely needed recruits burdened with a chronic illness, poor test scores, or a prior record of criminal assault and felony arrest. Never before in the history of the known world have so many people trooped through so many museums, been provided with so many handsome reproductions, dance recitals, string quartets, lectures, libraries, postcards. The opinion polls report two-thirds of the citizenry defining art as a necessity, but for the most part it is a constituency in the market for distraction, more interested in what Van Gogh’s deranged hand did to his ear than what his incomparable eye saw in the sunlight at Arles. The constituency is likened by

Jack Tworkov to a circle of spectators watching a sidewalk artist sketch portraits of Scottish terriers, what they admire having “nothing to do with art, but everything with performance: even costume plays a role (beard, beret, smock).”

I hate the whole race. There is no believing a word they say—your professional poets, I mean—there never existed a more worthless set than Byron and his friends for example.

—Duke of Wellington, 1810The preference has shaped the framing of the American mind since its inception in the colonial wilderness, the sensibility noted by Benjamin Franklin as being attracted to the invention of a machine or the improvement of an implement, more apt to make communion with objects that move and do things than with those that merely stand there waiting to be spoken to or heard. Not the kind of audience likely to object to the processing of the lively arts into the machine-made product distributed as media, the metamorphosis similar to the one visited upon the livestock in a Nebraska meat-packing facility. The songs and dances come with a factory-inspected guarantee that the commodity in the hand of the manufacturer will remain dead in the mind of the consumer.

The country continues to turn up individuals making works of art—among those in the literary theaters of operation I can think of many—but they traffic in a medium of exchange on which the society doesn’t place a high priority. Maybe it never did; maybe the way I remember the ’40s and ’50s is a tale told, if not by an idiot, by a trivial bourgeois or an obsolete romantic trapped in the dream of a lost golden age. The existence of a civilization presupposes a public that has both the time, and the need, to draw sustenance from the high-wire acts of the artistic imagination. The United States never has produced such a public in commercial quantity, a fact remarked upon by the art historian Robert Hughes in The Shock of the New. “Art discovers its true social use, not on the ideological plane, but by opening the passage from feeling to meaning—not for everyone, since that would be impossible, but for those who want to try. This impulse seems to be immortal.”

Happily so. What blocks the passage from feeling to meaning is the replacing of the thing itself with the price or theory of the thing, which is the difference between money and art as the universal medium of human exchange proposed by Arthur Schopenhauer. “Money is human happiness in abstracto, consequently he who is no longer capable of happiness in concreto sets his whole heart on money.” The dictum accords with the twentieth century’s wars and devourings of the earth, accounts for the modernistic expressions of alienation and despair, speaks to the price paid for the shark in formaldehyde. Although it’s frequently said that the truth shall make men free, the precept is almost as frequently misunderstood. Truth as synonym for liberty isn’t a collectible. It is the joyous discovery of the enlarged sense and state of being that is the change of heart induced by the presence, incomprehensible and usually unannounced, of the lady in the veil.