July 7

To John Bowring, secretary of the London Greek committee:

We sail on the twelfth for Greece. The Greek government expects me without delay.

In conformity to the desires of my correspondents in Greece, I have to suggest, with all deference to the committee, that a remittance of even “ten thousand pounds only” would be of the greatest service to the Greek government at present. I have also to recommend strongly the attempt of a loan, for which there will be offered a sufficient security by deputies now on their way to England. In the meantime, I hope that the committee will be enabled to do something effectual.

For my own part, I mean to carry up, in cash or credits, above eight, and nearly nine thousand pounds sterling, which I am enabled to do by funds I have in Italy and credits in England. Of this sum I must necessarily reserve a portion for the subsistence of myself and suite; the rest I am willing to apply in the manner which seems most likely to be useful to the cause—having, of course, some guarantee or assurance that it will not be misapplied to any individual speculation.

If I remain in Greece, which will mainly depend upon the presumed probable utility of my presence there, and of the opinion of the Greeks themselves as to its propriety—in short, if I am welcome to them—I shall continue, during my residence at least, to apply such portions of my income, present and future, as may forward the object—that is to say, what I can spare for that purpose. Privations I can, or at least could once, bear—abstinence I am accustomed to—and as to fatigue, I was once a tolerable traveler. What I may be now, I cannot tell—but I will try.

I await the commands of the committee. It would have given me pleasure to have had some more defined instructions before I went, but these, of course, rest at the option of the committee.

I have the honor to be

Your obedient, etc.

PS. Great anxiety is expressed for a printing press and types, etc. I have not the time to provide them, but recommend this to the notice of the committee. I presume the types must, partly at least, be Greek: they wish to publish papers, and perhaps a journal, probably in Romaic with Italian translations.

October

To Teresa, countess of Guiccioli:

Pietro has told you all the gossip of the island—our earthquakes, our politics, and present abode in a pretty village. I need say little on that subject. I was a fool to come here, but, being here, I must see what is to be done.

We are still in Cephalonia, waiting for news of a more accurate description, for all is contradiction and division in the reports of the state of the Greeks. I shall fulfill the object of my mission from the committee and then return into Italy. For it does not seem likely that, as an individual, I can be of use to them—at least no other foreigner has yet appeared to be so, nor does it seem likely that any will be at present.

We are very kindly treated by the English here of all descriptions. Of the Greeks, I can’t say much good hitherto, and I do not like to speak ill of them, though they do of one another.

November 29

To John Bowring:

The public progress of the Greeks is considerable, but their internal dissensions still continue. On arriving at the seat of government, I shall endeavor to mitigate or extinguish them—though neither is an easy task. I have remained here till now, partly in expectation of the squadron in relief of Missolonghi and partly to receive from Malta or Zante the sum of four thousand pounds sterling, which I have advanced for the payment of the expected squadron. The bills are negotiating, and will be cashed in a short time, as they would have been immediately in any other mart, but the miserable Ionian merchants have little money, and no great credit—and are besides, politically shy on this occasion, for although I had letters from one of the strongest houses of the Mediterranean, there is no business to be done on fair terms except through English merchants. These, however, have proved both able and willing—and upright, as usual.

Colonel Stanhope has arrived and will proceed immediately; he shall have my cooperation in all his endeavors, but from everything that I can learn, the formation of a brigade at present will be extremely difficult, to say the least of it. I regret to hear that the committee has exhausted their funds. Is it supposed that a brigade can be formed without them? Or that three thousand pounds would be sufficient? It is true that money will go further in Greece than in most countries, but the regular force must be rendered a national concern and paid from a national fund—and neither individuals nor committees, at least with the usual means of such as now exist, will find the experiment practicable.

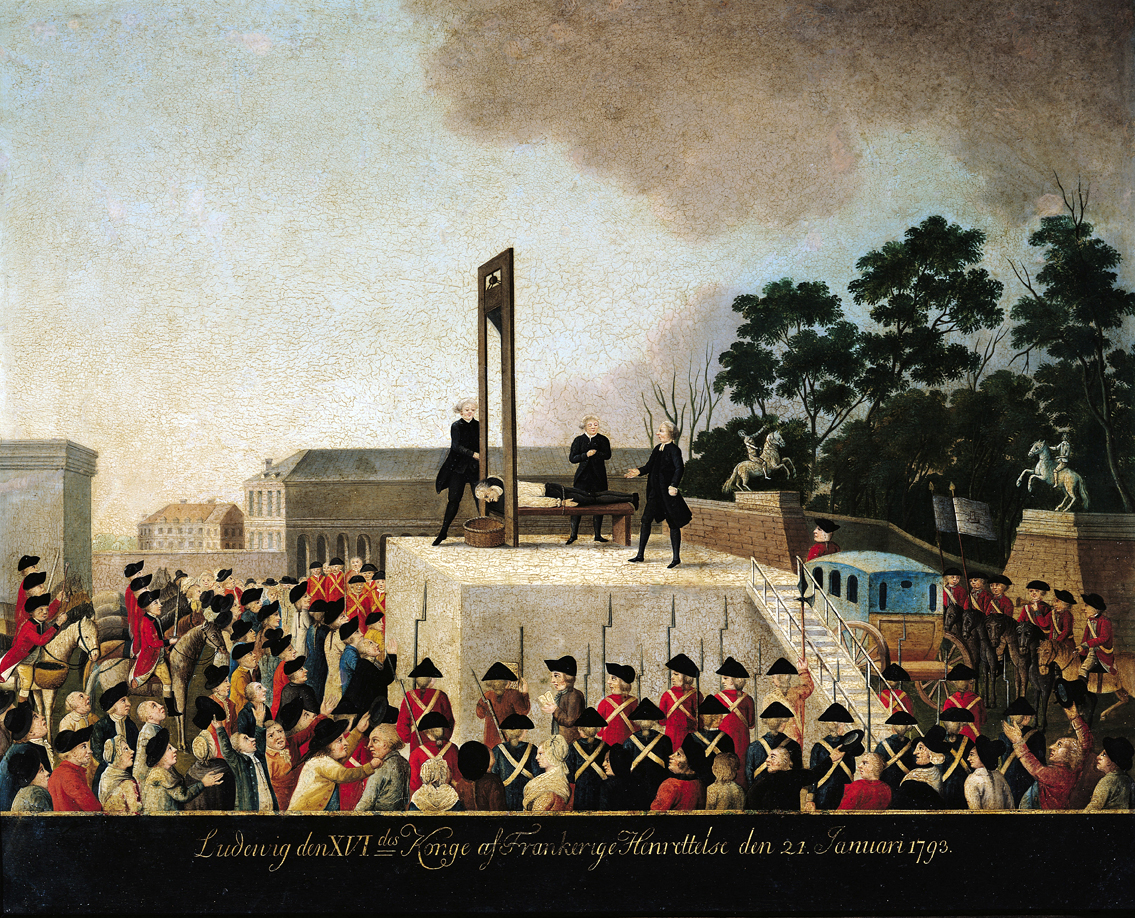

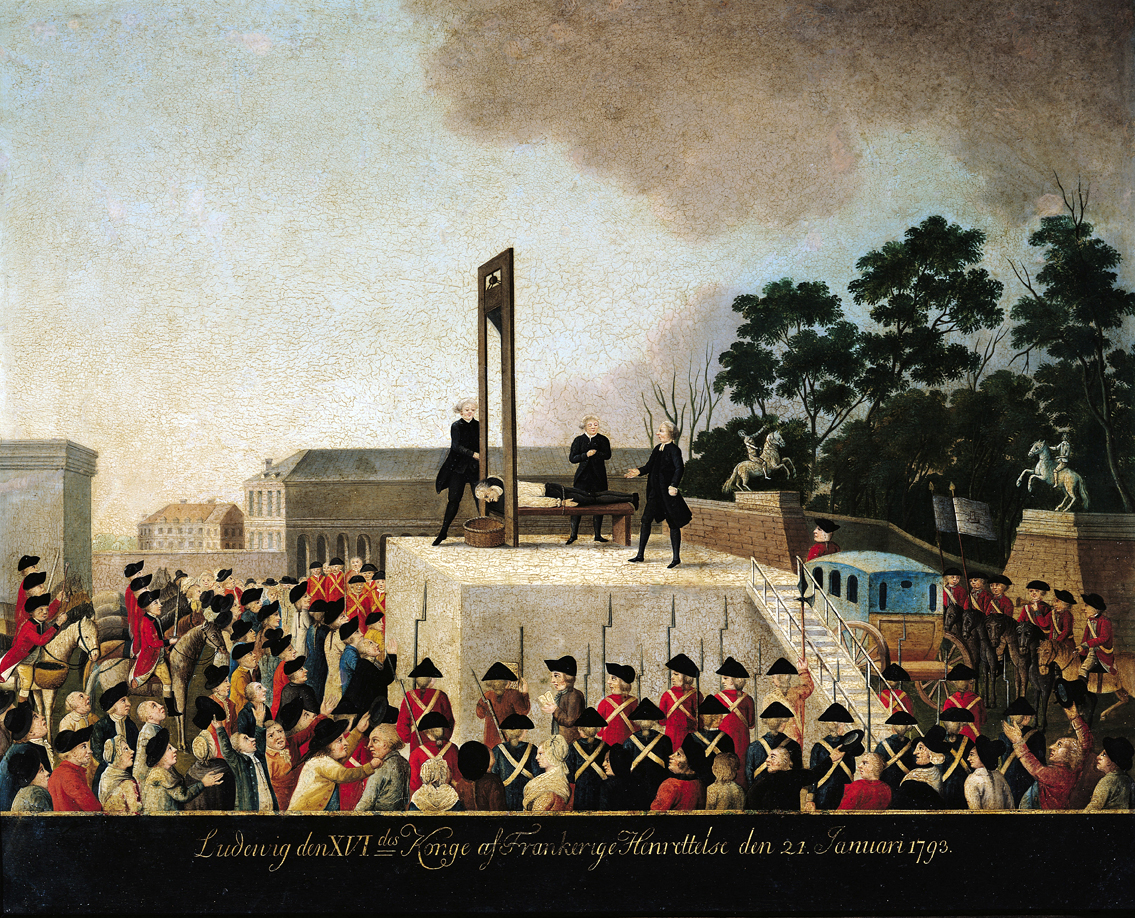

The Execution of Louis XVI, 21st January 1793, late eighteenth century. Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

November 30

To the general government of Greece:

The affair of the loan, the expectation so long and vainly indulged of the arrival of the Greek fleet, and the danger to which Missolonghi is still exposed, have detained me here, and will still detain me till some of them are removed. But when the money shall be advanced for the fleet, I will start for the Morea, not knowing, however, of what use my presence can be in the present state of things. We have heard some rumors of new dissensions, nay, of the existence of a civil war. With all my heart, I pray that these reports may be false or exaggerated, for I can imagine no calamity more serious than this; and I must frankly confess, that unless union and order are established, all hopes of a loan will be in vain; and all the assistance which the Greeks could expect from abroad—an assistance neither trifling nor worthless—will be suspended or destroyed; and, what is worse, the great powers of Europe, of whom no one was an enemy to Greece—and favor her establishment of an independent power—will be persuaded that the Greeks are unable to govern themselves, and will, perhaps, themselves undertake to settle your disorders in such a way as to blast the brightest hopes of yourselves and of your friends.

Allow me to add, once for all—I desire the well-being of Greece, and nothing else; I will do all I can to secure it, but I cannot consent, I never will consent, that the English public or English individuals should be deceived as to the real state of Greek affairs. The rest, gentlemen, depends on you. You have fought gloriously—act honorably toward your fellow citizens and the world. Let not calumny itself (and it is difficult, I own, to guard against it in so arduous a struggle) compare the patriot Greek, when resting from his labors, to the Turkish pasha, whom his victories have exterminated.

From his correspondence. Byron died of a fever in Missolonghi six months after the November 30 letter. As part of his grand tour beginning in 1809, Byron traveled to Greece for the first time, swam the Hellespont like the legendary Leander, and supposedly saved a girl from drowning. After the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage appeared in 1812, the duchess of Devonshire noted that the work “is on every table, and himself courted, visited, flattered and praised wherever he appears.” Caroline Lamb called the poet “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.”

Back to Issue