The Album (detail), by Édouard Vuillard, 1895. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection, Gift of Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg, 2000, Bequest of Walter H. Annenberg, 2002.

The last time I was in Paris I went to pay a call on a writer I admire. Like Balzac, Chopin, Oscar Wilde, Marcel Proust, Isadora Duncan, Gertrude Stein, and dozens of other luminaries, Raymond Roussel keeps a permanent address at 8, Boulevard de Ménilmontant, in the Cemitière du Père Lachaise, one of art’s most famous final resting places. But you won’t find flocks of tourists reverently camped out at his grave. No one lights candles for him or leaves him flowers, messages, metro tickets, smooth stones, or any other tokens of gratitude for the strange poems and even stranger novels he left to posterity. Not for Roussel’s tomb, as for Wilde’s, a recently installed glass case to protect the marble from the red lipstick of his fans.

The day I visited him, it was gray and rainy and cold. There were few people in the normally well-frequented cemetery. When I finally managed to locate Division 89, I was delighted to see a gaggle of fellow Rousselians hovering near his grave, umbrellas resting awkwardly on their shoulders as they snapped photos with evident excitement. But as I approached it became clear that they had their backs to his tomb. They were taking pictures of someone else. When the group cleared out, I looked at inscription on the black crypt that had attracted their attention. It read “Famille George Harrison” and had a large cross on top. Puzzled, I took my phone out of my pocket, did a quick Google search, and confirmed what I suspected: George Harrison, the real George Harrison, guitarist of the Beatles, died in Los Angeles and had his ashes scattered over the Ganges. Poor Roussel, I thought. Always being overshadowed by someone more famous.

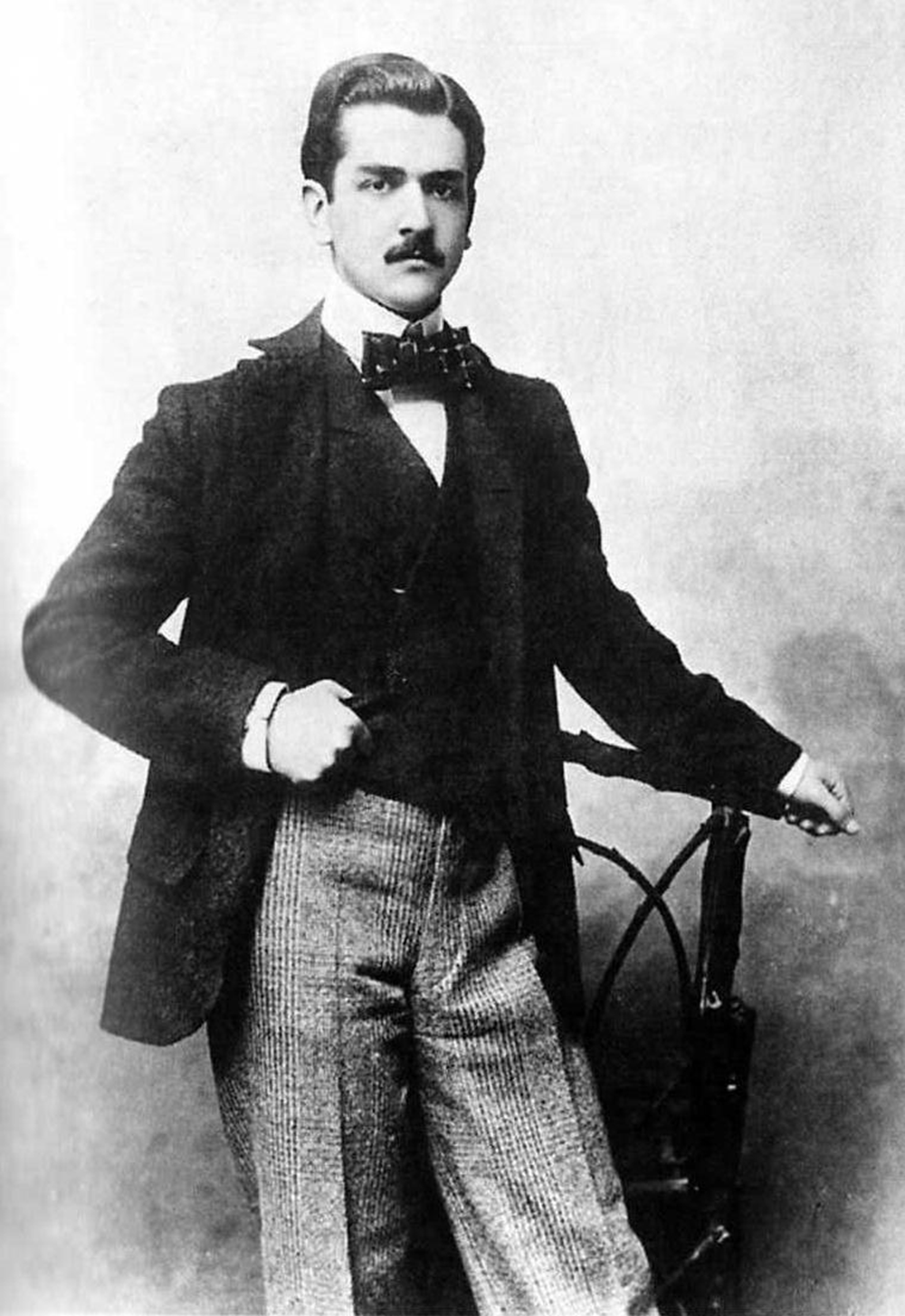

Born in 1877 to a family of wealthy lawyers and businessmen, and related by marriage to the Napoleonic aristocracy, Raymond Roussel was groomed by his overbearing, artistically inclined mother to be a classical musician. But an early experience with the ecstasies of language altered his career trajectory. At age nineteen, at work on what would become his first published book, he describes “a sensation of universal glory” that attended his writing process. He felt himself to be a prodigy whose achievement equaled that of Shakespeare, Dante, Victor Hugo, and Napoleon. He was certain, he later told his psychiatrist, that upon publication “the dazzling blaze” that had escaped from his pen and paper would “light up the universe.”

Needless to say, the reception of La Doublure—a lengthy novel in verse about a failed understudy—did not meet these high expectations. The French public’s indifference to the work crushed Roussel. He would go on to devote the better part of the sizable fortune he inherited to achieving the recognition that eluded him, but without success. His novels and collections of his poems, published and promoted at his own expense, took decades to sell out their first editions. The plays based on the novels, which he also bankrolled, were mocked by the French press when they were noticed at all. By the time of his suicide in Palermo in 1933, he had vastly scaled down his ambitions. In his final work, How I Wrote Certain of My Books, which explained the unusual method he used to compose his novels Impressions of Africa and Locus Solus and was published after his death, all he dared to hope for was “a little posthumous fame.”

Roussel did receive a little posthumous fame, but only that. After his death, his books were known to only a small coterie of “initiates.” What is astonishing, however, are some of the names on that coterie’s roll call. In France, he was a seminal influence on surrealism, Dadaism, the nouveau roman, and the Oulipo. André Breton, Michel Leiris, Jean Cocteau, Marcel Duchamp, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Raymond Queneau, and Georges Perec have all claimed Roussel as a precursor. Michel Foucault wrote his only book of literary criticism about Roussel’s oeuvre. In the United States and England, Roussel owes what reputation he has to the efforts of Harry Mathews and John Ashbery—whose journal Locus Solus, which introduced the New York School of Poets to the reading public, was named for Roussel’s novel—and to the poet Mark Ford, who published Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams, the only biography of the writer in English. More recently, British artist Brian Catling’s popular historical fantasy novel The Vorrh pays homage to Impressions of Africa by including Roussel as a character.

All of these writers and artists achieved a level of success that Roussel would have envied, and while each has enthusiastically championed Roussel’s work, their fame does not seem to have rubbed off on him. He remains known not just as a writer’s writer but as an experimental writer’s experimental writer—or, in the words of one American publisher, a “cult author extraordinaire.” He is still regarded by the French literary establishment as something of a curiosity, and while his work remains in print, his only appearance in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade series—the gateway to canonization in France—is on the cover of Foucault’s book. Every so often, there will be a periodic attempt to revive his work in the United States, but these never seem to be successful. By my calculations, the last one occurred in 2011–12, when four new editions of his books were published. This year New Directions makes another valiant attempt, with a reissue of Rupert Copeland Cunningham’s translation of Locus Solus.

I have often wondered why, with friends such as these, Roussel isn’t better known than he is. Admittedly, his poems and novels are difficult and obscure, strange hybrids of the ultra-conventional and the ultra-unconventional. The early poems, for example, were written in an academic style, in rhyming alexandrines. They read like prose but are only superficially narratives: of the 318 pages of La Doublure, nearly two-thirds are devoted to a detailed description of a carnival in Nice; the two thousand lines of La Vue describe a beach scene set into the lens of a souvenir penholder, while the thousand lines of La Concert and La Source detail the sketch of a hotel on hotel stationery and the label on a bottle of mineral water respectively.

The prose works, conversely, read like surrealist poetry. They were written according to a compositional method Roussel called le procédé (the procedure), in which a complicated system of puns rather than traditional narrative logic determines the progression of the story. In Locus Solus, the mad scientist Martial Canterel takes his colleagues on a tour of his country estate—“the lonely place” of the title—to show them the bizarre inventions generated by Roussel’s procédé. These include a device that constructs a mosaic made out of human teeth; a water-filled diamond in which a dancer, a hairless cat, and the head of Danton are suspended; and a series of corpses Cantarel has brought back to life with the fluid “ressurectine,” which compels them to act out the most important event of their former lives, to the scientists’ astonishment.

Difficulty and obscurity aren’t in themselves impediments to recognition, of course. Books written by Roussel’s famous admirers are hardly crowd-pleasing beach reads. In Other Traditions, which includes lectures on Roussel and five other “minor poets,” Ashbery writes that canonization is as much a matter of “happenstance as intrinsic merit.” This may be true but lacks explanatory power. Ashbery is correct to note that long-term literary success has a great deal to do with a number of factors that are, properly speaking, extra-literary, but it is not therefore as indeterminate or random as he suggests.

To get to the bottom of the mystery of Roussel’s literary reputation, I turned to a book by his fellow resident in the Père Lachaise, the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. In The Rules of Art, a study of French literature in the age of Flaubert, Bourdieu develops a comprehensive theory of what he calls “the literary field.” Writers have long flattered themselves into thinking their work floats above such sordid matters as class, commerce, politics, and careerism, but Bourdieu shows that this is a myth. The “literary field,” as he describes it, is no disinterested meritocracy; it’s the setting for an often brutal struggle for canonization. Whether writers receive or fail to receive recognition has just as much to do with the symbolic positions they hold within the field as the actual quality of their writing. The reception that awaits writers’ works is invariably colored, if not wholly determined, by the houses and magazines they publish with, the prestige of the literary tastemakers who champion or pan their works, the size and social standing of their audience, and the positions they take on pressing political and aesthetic issues, as well as the particular features of their personal lives and family backgrounds. According to Bourdieu, the initial reception of a writer’s work will give him an indication of the “objective truth of the position he occupies and his probable future.” Failures, discouragements, warnings, exclusions—all of which he labels “negative sanctions”—generally cause a writer to redefine his creative project or to retreat from the field in defeat.

The redefinition of the creative project usually takes one of two forms. The first is typical of avant-garde writers from Flaubert to Breton to the present: the writer can make a virtue out of necessity by deliberately and haughtily courting commercial failure. He can increase the unconventionality, difficulty, or offensiveness of his work in order to épater la bourgeoisie, turning his writing into the fetish of disinterested art pour l’art, which knows only “symbolic profits” and disdains actual profits. The second is more accommodating: the writer can attempt to better adapt his work to the conventions of writing expected by the reading public and rewarded by it with sales, reviews, prizes, nominations to academies, and so on. The latter is more likely to receive short-term profits, while the former, if his work survives, could achieve long-term success in a “loser takes all” market in which economic failure contributes to symbolic success and a writer’s initial indifference to power, honors, and wealth are rewarded with power, honors, and wealth. Bourdieu compares this indifference to an investment of capital that is paid back with interest when the writer’s career reaches maturity (though this sometimes happens only after his death).

Seen through this lens, what probably sunk Roussel’s career was that neither he nor his work fit naturally into the market for commercial art or into the putatively autonomous market of avant-garde art. The paradox of Roussel’s career is that, after a series of early failures, he did not retreat from the field, reconvert his creative project to make common cause with the avant-garde, or embrace the conventions of the popular fiction he himself enjoyed. He aimed highly unconventional writing at a bourgeois public with the expectation that it would sell and was baffled when it didn’t. His writing anticipated the imagery of surrealism; the affectless descriptions of the nouveau roman; and, through the procédé, Oulipian constraints—but he wanted the audience of Victor Hugo or Jules Verne or at least that of his friend Edmond Rostand, author of Cyrano de Bergerac. Roussel could have attempted to go the way of a popular writer like Rostand or of an avant-garde writer like Breton, but, both admirably and foolishly, he remained Roussel to the end.

If Roussel didn’t stop writing altogether after the first few failures, it is undoubtedly because he had a private income that saved him from the necessity of doing remunerative labor. But in fact it was his class position that prevented him from achieving consciousness of himself as an avant-garde artist. His political opinions and aesthetic tastes did not deviate much from what might be expected from the members of his class. Although few people were less cut out for it than he, Roussel regarded military service as a patriotic duty and fought in World War I. Far from being above or indifferent to power and honors and wealth, he had a sincere respect for social institutions like the Académie Française and the Légion d’Honneur. He had great enthusiasm for genre writers like Loti and Verne, and his love of Wagner and Gounod was equally outmoded. He preferred his mother’s box seat in the Opéra Comique and the Théâtre Français to sitting in the rafters of the experimental theaters in Montparnasse. He was resolutely Right Bank.

Much of his work was first serialized in Le Gaulois de Dimanche, which drew its readers (including Roussel’s mother), from the conservative, monarchist segments of the nobility and Grande Bourgeoisie. It was edited by an irredeemable square, Arthur Meyer, who said of the paper: “People made fun of Le Gaulois saying that it was trying to be a branch office of the Académie Française. This criticism, I must say, made me rather proud.” Far from putting him off, Meyer’s reference to the Académie Française and the social composition of Le Gaulois’ readership would have appealed to what Michel Leiris called “Roussel’s mania for established reputations” in one of his essays on the life and work of his family friend.

Precisely the same mania might have drawn Roussel to the Lemerre publishing house. While most young writers would have placed their work with boutique presses on the Left Bank, Roussel tied his career to the publisher of the Parnassian poets, who reached the height of their popularity during Flaubert’s time. Roussel was publishing writing two artistic generations ahead of its time with a firm two artistic generations out of date.

The result was a disaster. Lemerre may have published the books only because Roussel paid for the print runs and publicity. When it came to Roussel’s books, Lemerre proved an incompetent publisher who didn’t even bother to apply for copyrights. And while it did nothing to reach the bourgeois audience Roussel longed for, publishing with the firm harmed his reputation among tastemakers like André Gide, the novelist and editor of the Nouvelle Revue Français. “I hardly thought to open it,” Gide said of Roussel’s collection Pages Choisies, “since I expected nothing good from” Lemerre.

Despite Roussel’s objections, during his lifetime he was grouped with the Dadaists and the Surrealists. “I am being called a Dadaist,” he wrote Leiris in exasperation. “I don’t know what Dadaism is!” Breton and Duchamp, consciously behaving like members of an avant-garde, were initially attracted to his plays because of the effect they had on the public. (Duchamp writes of the staging of the Impressions: “It was pure bizarre madness. I cannot remember much about the words. We didn’t listen a lot.”) But although Roussel preferred ridicule to indifference, he was genuinely upset by the scandals his plays caused and by the hostility of well-to-do Parisian theatergoers to his work.

So while Roussel was grateful for the surrealists’ interest, he remained aloof, refusing to join their movement or grant interviews for their magazines. To Lugné-Poe, the director of Ibsen and Strindberg, who was then organizing a European tour of the theatrical version of Locus Solus, he admitted, without apparent irony, that he found the surrealists “un peu obscur.”

This comment is typical of Roussel, who was, in one respect at least, a naive artist. In his only reference to Roussel in The Rules of Art, Bourdieu calls him an “outsider artist,” in the art brut tradition of a painter like Douanier Rousseau or a novelist-artist like Henry Darger. But while Roussel’s novels share the childlike innocence of “The Sleeping Gypsy” or In the Realms of the Unreal, what makes Roussel a naive artist is his total lack of awareness of the particular position he occupied in the literary field. As a result, he was incapable of framing or positioning his writing in such a way that it reached the audience for avant-garde writing that could have nurtured it to the long-term success many of the surrealists have enjoyed. It is no coincidence that his most influential book was the one he was not responsible for publishing. After his death, Leiris had How I Wrote Certain of My Works printed in the Nouvelle Revue Français, where his writing ought to have appeared all along.

The avant-garde derives from a military-political metaphor, in which artists are analogous to the group of soldiers or members of a revolutionary party who “advance” into battle before the rest of the group. Although artists are fighting only over symbolic terrain—the avant-garde seeks to overthrow and replace established conventions that regulate what can be represented and how it can be represented—considerations of class are just as relevant to the artist’s struggle for canonization as they are to an army’s or revolutionary party’s struggle for power. In fact, where the biographies of individual artists are concerned, the two are intimately related.

Breton, for example, came from a provincial, working-class background and would have been excluded on these grounds from rising within established cultural institutions. It was thus quite natural for him to disdain commercial profits (which would not have been forthcoming to him anyway) in favor of spiritual profits. Breton organized a group, published a manifesto, and attacked the aesthetic conventions of the bourgeoisie, modeling himself on the communist movement he would later join and placing surrealism in the service of the revolution. Perhaps Roussel kept his distance from surrealists like Breton because of the great divergence in their class backgrounds and political opinions. Because he already occupied a space in the class hierarchy from which Breton was excluded, Roussel was unlikely to use the vocabulary of leftist politics to describe his own work.

What is key to our appreciation of artistic revolutions is not necessarily their political content but what Bourdieu calls their “spirit of contestation” and their “indifference to money.” This spirit is directly correlated with their canonization by later generations, terms that derive not from war and revolution but from religion. Since the “pure art” revolution of Flaubert, Baudelaire, and Manet during the Second Empire, art has come to be perceived as a semi-sacred activity that requires artists to make a show of disdaining commercial and social recognition because these are inadequate to and unworthy of the “pearls without price” of artistic production. These gestures are intended to create the illusion that, in a capitalist society, a work of art is not what it really is: a commodity.

However eccentric his writing may appear, Roussel lacked both the spirit of contestation and the indifference to money that are essential for canonization. While he did not need the money from royalties or box-office receipts to survive and continue writing, he measured success in terms of sales and seats, as well as in recognition from the literary and social establishment. His audience didn’t fail to notice his hunger for their approval—when they weren’t wondering whether Roussel was having a joke at their expense, they were mocking him for the amount of money he put into producing, publishing, and publicizing his work. He neither obeyed the conventional expectations of his audience nor explicitly challenged them. His writing was truly revolutionary, but he never positioned it as such during his lifetime.

When writers like Robbe-Grillet, Perec, and Ashbery used the techniques he pioneered, they did so deliberately in the spirit of contestation that helped define the avant-garde. They have been rewarded with the recognition that eluded Roussel in his lifetime and the canonization that continues to elude him to this day. The result is that his stylistic innovations and compositional discoveries have survived, while he and his books have come close to falling through the cracks of literary history.

Roussel’s fate remains a cautionary tale for writers and readers who believe the only thing that lies between merit and recognition is a little luck and a certain amount of time. It is a tale whose moral may be contemplated seven days a week in an otherwise empty corner of the Père Lachaise. If you go, do as I did and leave Roussel your metro ticket. He will be eternally grateful to you.