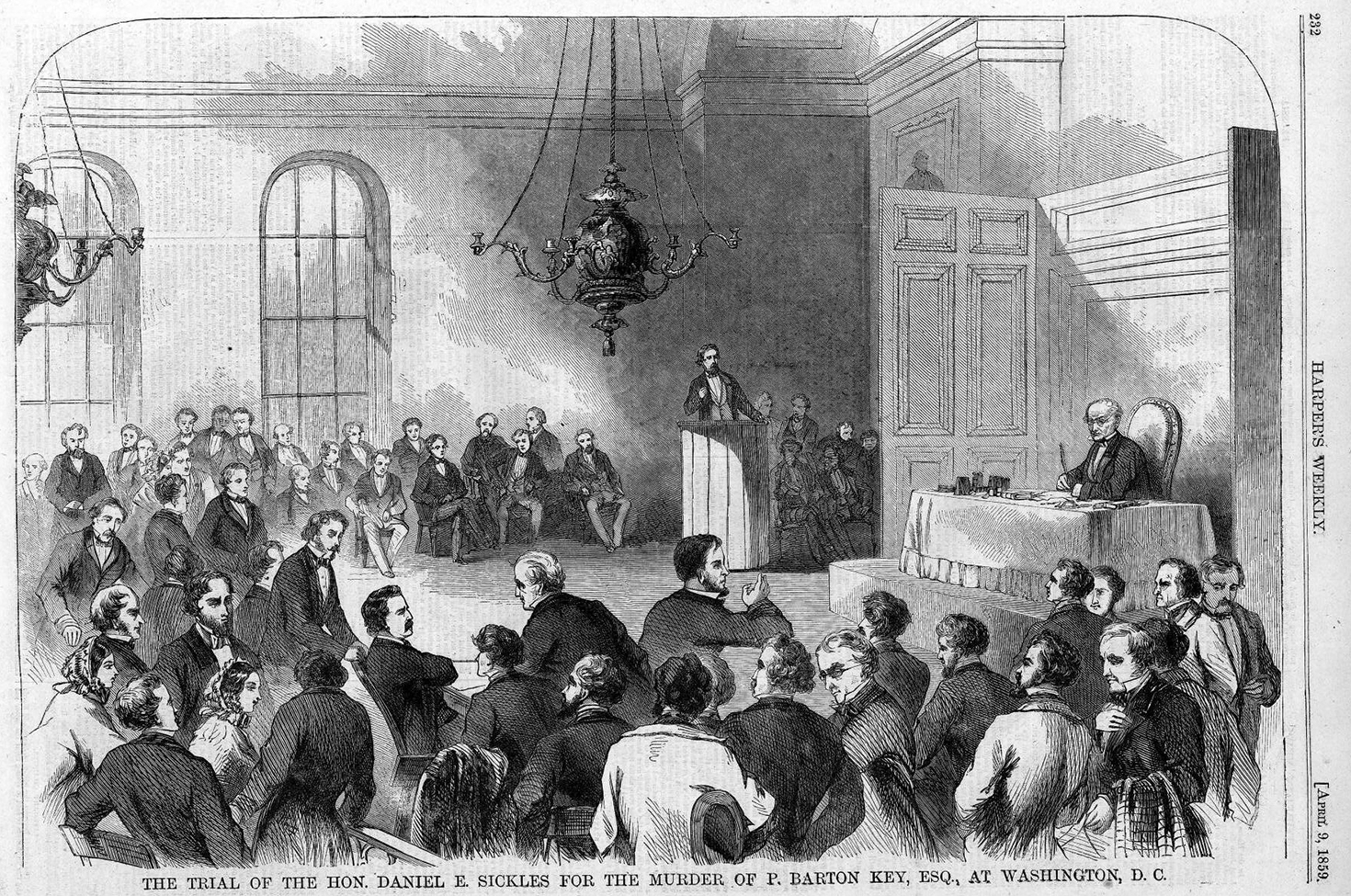

Harper’s Weekly engraving of the Dan Sickles murder trial in Washington, DC, 1859. Wikimedia Commons.

Legal scholar W. Mikell tells us that “The fundamental question with respect to the insanity defense is always this: what kind and degree of insanity should excuse its victim from punishment for an act that, if done by a sane person, would bring upon him the sanction of the law?”

In 1639 Dorothy Talbye was executed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Governor Winthrop’s diary tells us that Mistress Talbye “had been of good esteem for godliness but falling at difference with her husband, through melancholy or spiritual delusion, she sometimes attempted to kill him, and her children, and herself.” She was excommunicated from the church and whipped, “whereupon she was reformed for a time, and carried herself more dutifully to her husband, etc.; but soon after she was so possessed with Satan, that he persuaded her (by his delusions, which she listened to as revelations from God) to break the neck of her own child, that she might free it from future misery.” Her execution by hanging was ordered after she confessed to the crime when threatened with being pressed to death. Winthrop concludes with “Mr. Peter, her late pastor, and Mr. Wilson, went with her to the place of execution, but could do no good with her.” From this account, it very much sounds like Dorothy Talbye suffered from severe postpartum psychosis, not demonic possession. But in 1639 the treatment was death.

In 1724 an English commoner named Edward Arnold shot Lord Onslow for sending “devils and imps” that had “invaded his belly and his bosom such that he could not sleep.” Arnold’s defense attorney argued that he was insane—delusional and incapable of normal reason—and, therefore, not guilty. He pointed out that previous cases had held that “guilt arises from the mind and the wicked will and intention of the man. If a man be deprived of his reason, and consequently of his intention, he cannot be guilty.”

The prosecution and defense both agreed that the defendant suffered from insane delusions and that these were the cause of his act. The judge ruled that a man is not guilty by reason of insanity only if he was “totally deprived of his understanding and meaning, and doth not know what he is doing, no more than a brute, or a wild beast,” noting that “such a one is never the subject of punishment.” This became known as the “wild beast” test of insanity, and it required “absolute insanity”—that is, no ability whatever to reason or understand.

Arnold was convicted and sentenced to hang because he had known that he was shooting a man. (This was later commuted to a life sentence at the urging of Lord Onslow, who survived.) This is strictly a cognitive test, one that does not take into account the derangements in reality, understanding, or reasoning that can characterize severe mental illness.

By 1800 some progress had been made in understanding the nature of mental illness, particularly with regard to two concepts: that a psychotic delusion does not arise from bad character or an intentional choice to do evil, and that a person can be deranged and delusional on some subjects, depending on which brain area is affected, while remaining relatively intact and rational on others. My father, who recently had a massive stroke that destroyed much of the right side of his brain, can discuss contemporary events and modern astrophysics with perfect probity but cannot realize that his entire left side is paralyzed or even that he has a left side. He believes he is perfectly normal and keeps demanding that his bicycle be brought to him for a ride.

This brings us to the case of Rex v. Hadfield in 1800. James Hadfield had suffered serious head wounds from saber blows in His Majesty’s service against the French and had come to believe that he, like Jesus Christ, had to be sacrificed in order to redeem mankind. Suicide being out of the question because it was a sin, Mr. Hadfield came up with a plan. He took a pistol to the theater at Drury Lane and attempted to assassinate King George III, who was in attendance, so that he would be executed and bring in the new millennium. He rose, said, “God bless your Royal Highness; I like you very well, you are a good fellow,” and pulled the trigger. He missed (otherwise history might have been different) but was charged with attempted murder.

His defense attorney, Thomas Erskine, pled insanity on his behalf. Erskine acknowledged that Hadfield had planned and executed the crime and appeared coherent, but argued for further consideration:

It is agreed by all jurists, and is established by the law of this and every other country, that it is the Reason of Man which makes him accountable for his actions; and that the deprivation of reason acquits him of crime. This principle is indisputable; yet so fearfully and wonderfully are we made, so infinitely subtle is the spiritual part of our being, so difficult it is to trace with accuracy the effect of diseased intellect upon human action, that I may appeal to all who hear me, whether there are any cases more difficult…as when insanity, or the effects and consequences of insanity, become the subjects of legal consideration and judgment.

Erskine introduced testimony by three physicians—perhaps the first case in which experts offered opinions as to a defendant’s state of mind—that Hadfield did indeed suffer from delusions that had resulted from his head injury. Erskine then argued that you cannot define insanity as not knowing the difference between right and wrong: Hadfield knew that murder was generally wrong but, due to his delusion, believed that he was doing a greater good for mankind. Erskine urged the court to recognize that entirely rational behavior can follow from an irrational idea, a mad delusion.

A successful insanity defense at that time, however, required that if the defendant be “lost to all sense, in consequence of the infirmity of disease, that he is incapable of distinguishing between good and evil—that he is incapable of forming a judgment upon the consequences of the act which he is about to do, that then the mercy of our law says, he cannot be guilty of a crime.” And Hadfield had clearly carefully planned and executed his strategy with full understanding that he would be hanged for murder if he succeeded; this was his specific wish and intent, in fact. He surely had been no “wild beast”; he knew, in one sense, what he was doing.

The defense attorney persisted, arguing that delusion was “the true character of insanity” and reminded the court of Hale’s commentary: “The true rule is, to judge…whether there was that competent degree of reason which enabled the person accused to judge whether he was doing right or wrong.”

The judge, convinced of Mr. Hadfield’s clear psychosis, declared that the verdict “was clearly an acquittal.” In so doing, he explicitly rejected the “wild beast” test, the requirement that a man must be “wholly” without reason, as well as the simple cognitive test, that a man is not insane if he can distinguish between right and wrong, even if he is delusional as to his own acts. But he also ruled that “the prisoner, for his own sake, and for the sake of society at large, must not be discharged.”

Up until this time, defendants found not guilty due to insanity were generally released; there was no legal authority for holding a man who was not convicted. To fix this, Parliament quickly passed the Criminal Lunatics Act of 1800, legalizing the indefinite detention of insane defendants, and Hadfield spent the rest of his life in psychiatric confinement at Bedlam.

When William Blackstone, the noted English jurist, addressed the state of the insanity defense in 1803, he advised that the focus should be on a defendant’s consciousness of guilt and the ability to discern between good and evil. He endorsed the execution of children as young as eight if they appeared to have some consciousness of guilt. In one case, a child ran and hid, proving, Blackstone reasoned, that he knew he had done wrong and was, therefore, guilty. This was during the time of the “Bloody Code,” when 220 offenses were punishable by death.

As to an “idiot” or “lunatic,” Blackstone said, “the rule of law…is that furiosus furore solum punitur (a madman is punished by his madness alone)…Where there is a defect of understanding…there is no discernment, there is no choice; and where there is no choice, there can be no act of the will” and thus no blame (italics added). And so, Blackstone concluded, “In criminal cases, therefore, idiots and lunatics are not chargeable for their own acts, if committed when under these incapacities.” He seems to say that a person who knows the difference between right and wrong is still not morally or legally culpable if their mental illness prevents them from exercising free will and choice.

But the bar was set very high; it favored a presumption that a person was of sound mind, possessed sufficient intelligence, and, if over age eight, knew right from wrong. It favored, in other words, an assumption of guilt. An absence of will must be absolute in a lunatic, and an absence of knowledge and reason absolute in an idiot; there must be no scintilla of discernment, no sliver of free choice, and no exercise of will.

The law proceeds unevenly, subject to the vicissitudes of public and political pressure, and bad facts often make bad law. Hadfield’s case had little impact on future insanity cases. A scant twelve years later—the blink of an eye in terms of legal evolution—John Bellingham assassinated Sir Spencer Perceval, the prime minister, in the House of Commons. He was not assigned an attorney until the night before his trial, and though clearly delusional, he was summarily hanged eight days later (under pressure from the Crown) because he was presumed to “know” the difference between good and evil and to have chosen evil. Thus did a bad case make bad law, its impact felt for years in the form of precedent.

Still, the general trajectory of the insanity defense over time has been to recognize that some people are not in control of their reasoning or behavior, because of mental illness, and are, therefore, not criminally culpable. In 1840 a man named Edward Oxford fired a pistol at Queen Victoria. Presented with evidence that Oxford had long been unstable and that the pistols had not even been loaded, the judge instructed the jury, “If some controlling disease was, in truth, the acting power within him, which he could not resist,” then he was not criminally responsible. The jury found Oxford not guilty by reason of insanity, and he was committed to Bedlam for twenty-four years. (At that point, he was released on the condition that he emigrate to Australia and never return. He became a model citizen there.)

Queen Victoria, incensed at Oxford’s escape from the hangman, wrote to Sir Robert Peel, “Punishment deters not only sane men but also eccentric men, whose supposed involuntary acts are really produced by a diseased brain capable of being acted upon by external influence. A knowledge that they would be protected by an acquittal on the grounds of insanity will encourage these men to commit desperate acts, while on the other hand certainty that they will not escape punishment will terrify them into a peaceful attitude toward others.” But I’ve yet to either meet or hear of a person with insane delusions who is dissuaded from them or their commands by reason or the promise of punishment. It would be comforting to think that they can be deterred by such threats, but it simply isn’t so. The wish is a vain wish, a sort of urban myth.

Excerpt from Nobody’s Child: A Tragedy, a Trial, and a History of the Insanity Defense by Susan Vinocour. Copyright © 2020 by Susan Vinocour. Reprinted with permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.