Le Ministère Attaqué du Choléra Morbus, by Grandville, 1831. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

In the weeks ahead, as the world continues to reckon with and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories dealing with quarantine, unfathomable deaths, isolation, dread, and attempts to find community when the rest of the world feels far away.

The poet and critic Heinrich Heine reportedly once said that if you asked a fish how it felt in water, it would say, “Like Heine in Paris.” Born in Dusseldorf, Heine moved to Paris in 1831, attracted by the liberal regime of France’s new king, Louis-Philippe (brought to power the year before in the July Revolution), and by the growth of the utopian socialist movement Saint-Simonianism. In Paris Heine found both steady work and a level of literary fame he hadn’t achieved back home. He lived there for the rest of his life.

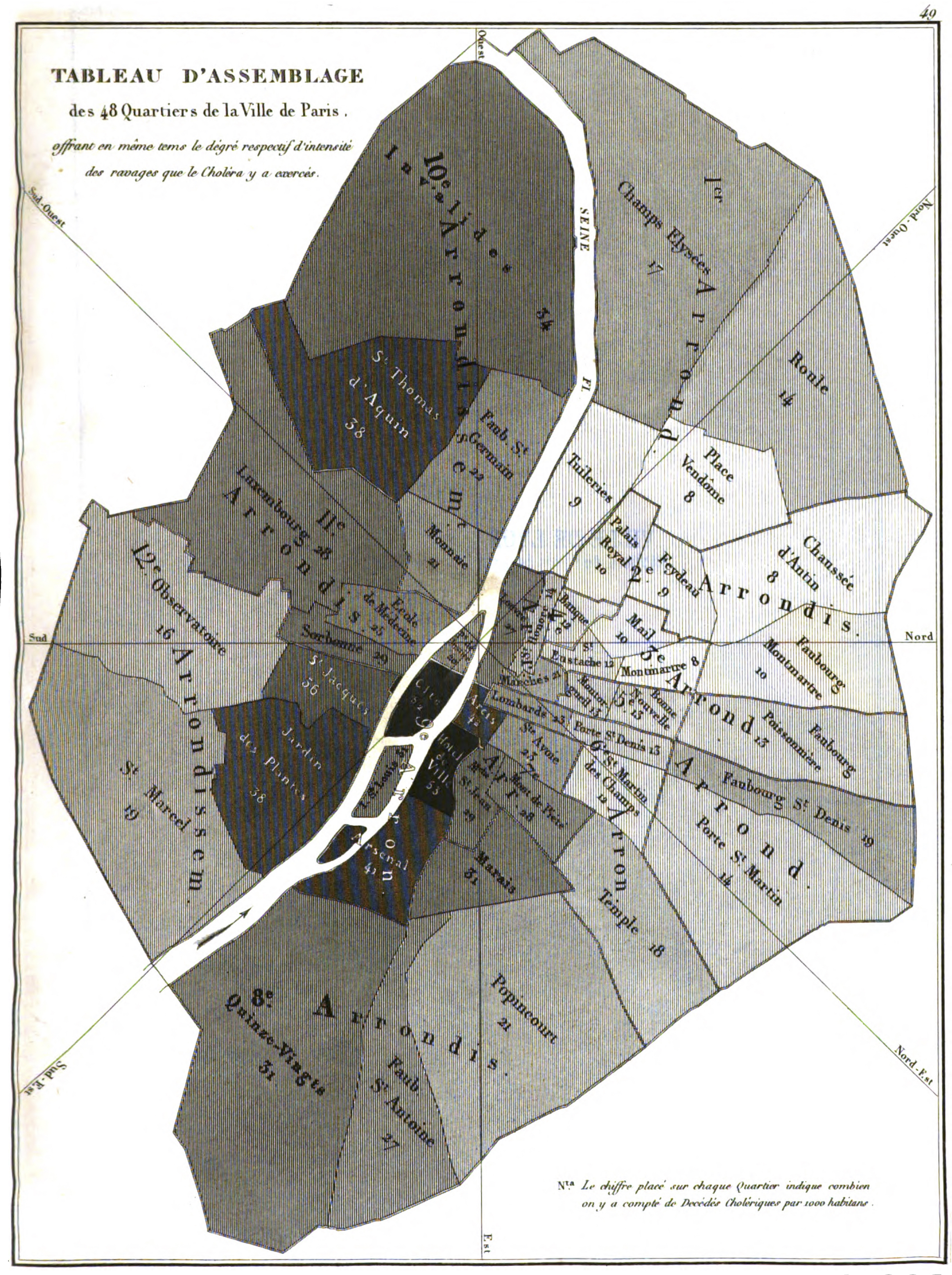

In 1833 Heine published French Affairs: Letters from Paris, a collection of his columns on life in Paris written for an Augsburg newspaper. It included a day-by-day account of the June uprising of 1832, later immortalized in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. It also included a report on the 1832 cholera outbreak, part of a widespread pandemic that affected parts of Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Over six months the disease killed almost twenty thousand people in Paris alone. The following excerpt is drawn from Heine’s column dated April 19, 1832, adapted from the 1893 translation by Charles Godfrey Leland.

Its arrival was officially announced on the 29th of March, and as this was the day of Mid-Lent, and there was bright sunshine and beautiful weather, the Parisians hustled and fluttered the more merrily on the boulevards, where one could even see maskers, who, in caricatures of livid color and sickly mien, mocked the fear of the cholera and the disease itself. That night the balls were more crowded than usual; excessive laughter almost drowned the roar of music; people grew hot in the chahut, a dance of anything but equivocal character; all kinds of ices and cold beverages were in great demand when all at once the merriest of the harlequins felt that his legs were becoming much too cold and took off his mask, when, to the amazement of all, a violet-blue face became visible. It was at once seen that there was no jest in this; the laughter died away; and at once several carriages conveyed men and women from the ball to the Hôtel Dieu, the Central Hospital, where they, still arrayed in mask attire, soon died. As in the first shock of terror people believed cholera was contagious, and as those who were already patients in the hospital raised cruel screams of fear, it is said that these dead were buried so promptly that even their fantastic fools’ garments were left on them, so that as they lived they now lie merrily in the grave.

There rose all at once a rumor that many of those who had been so promptly buried had died not from disease but by poison. It was said that certain persons had found out how to introduce a poison into all kinds of food, be it in the vegetable markets, in bakeries, meat stalls, or wine. The more extraordinary these reports were, the more eagerly were they received by the multitude, and even the skeptics must necessarily believe in them when an order on the subject was published by the chief of police. For the police, who in every country seem to be less inclined to prevent crime than to appear to know all about it, either desired to display their universal information or else thought, regarding the tales of poisoning, that whether they were true or false, they themselves must in any case divert all suspicion from the government—suffice it to say that by their unfortunate proclamation, in which they distinctly said that they were on the track of the poisoners, they officially confirmed the rumors, and thereby threw all Paris into the most dreadful apprehension of death.

“We never heard the like!” said the oldest people, who, even in the most dreadful times of the Revolution, had never experienced such fearful crime. “Frenchmen! We are dishonored!” cried the men, striking their foreheads. The women, pressing their little children in agony to their hearts, wept bitterly and lamented that the innocent babes were dying in their arms. The poor people dared neither eat nor drink, and wrung their hands in dire need and distress. It seemed as if the end of the world had come. The crowds assembled chiefly at the corners of the streets, where the red-painted wine shops are situated, and it was generally there that men who seemed suspicious were searched, and woe to them when any doubtful objects were found on them. The mob threw themselves like wild beasts or lunatics on their victims. Many saved themselves by their presence of mind, others were rescued by the firmness of the Municipal Guard, who in those days patrolled everywhere; some received wounds or were maimed, while six men were unmercifully murdered outright. Nothing is so horrible as the anger of a mob when it rages for blood and strangles its defenseless prey. Then there rolled through the streets a dark flood of human beings in which, here and there, workmen in their shirtsleeves seemed like the white caps of a raging sea, and all were howling and roaring—all merciless, heathenish, devilish. In the rue de Vaugirard, where two men were killed because certain white powders were found on them, I saw one of the wretches while he was still in the death rattle, and old women plucked the wooden shoes from their feet and beat him on the head till he was dead. He was naked and beaten and bruised, so that his blood flowed; they tore from him not only his clothes but also his hair, and cut off his lips and nose; and one blackguard tied a rope to the feet of the corpse and dragged it through the streets, crying out, “Voilà le cholera morbus!”

It appeared the next day in the newspapers that the wretched men who had been so cruelly murdered were all quite innocent, that the suspicious powders found on them consisted of camphor or chlorine or some other kind of remedy against cholera, and that those who were said to have been poisoned had died naturally of the prevailing epidemic. The mob here, like the same everywhere, being quick to rage and readily led to cruelty, became at once appeased, and deplored with touching sorrow its rash deeds when it heard the voice of reason. With such voices the newspapers succeeded the next day in calming and quieting the populace, and it may be proclaimed, as a triumph of the press, that it was able to so promptly stop the mischief that the police had made.

Since these events all has become quiet again. There is a stony stillness as of death in every face. For many evenings very few people were seen on the boulevards, and they hurried along with hands or handkerchiefs held over their faces. The theaters are as if perished and passed away. When I enter a salon, people are amazed to see me still in Paris, since I am not detained by urgent business. In fact, most strangers, and especially my fellow countrymen, left long ago. Obedient parents received from their children orders to return at once. God-fearing sons fulfilled without delay the tender wishes of their loving sires, who longed to see them in their homes again—honor thy father and thy mother, then thy days shall be prolonged upon the earth! In others, too, there suddenly awoke an endless yearning for their fatherland, for the romantic valleys of the noble Rhine, for the dear mountains, for winsome Swabia, the land of pure true love and woman’s faith, of joyous ballads and of healthy air. It is said that thus far more than 120,000 passports have been issued at the Hôtel de Ville.

Although the cholera evidently first attacked the poorer classes, the rich still very promptly took flight. M. Aguado, one of the richest bankers and a chevalier of the Legion of Honor, was field marshal in this great retreat. The knight is said to have glared with mad apprehension out of the coach window and believed that his footman all in blue who stood behind was blue Death himself or the cholera morbus.

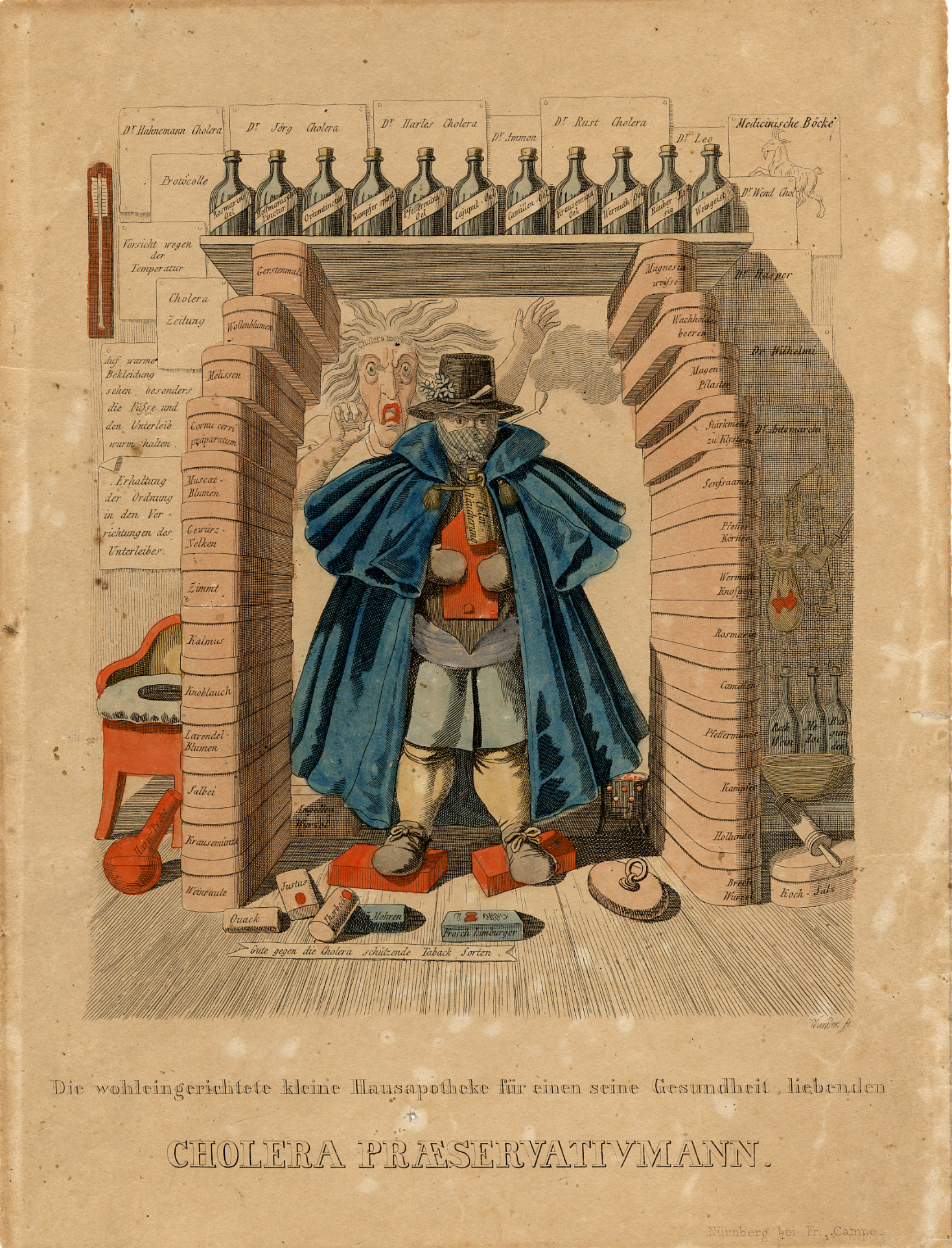

The multitude murmured bitterly when it saw how the rich fled away and, well packed with doctors and drugs, took refuge in healthier climes. The poor man saw with bitter discontent that money had become a protection also against death. But the whole royal family has behaved quite nobly in this sad time. When cholera broke out, the queen assembled her friends and servants and distributed among them flannel bandages, which were mostly made by her own hands. The manners and customs of ancient chivalry are not yet extinct; they have only changed into domestic citizen-like forms: great ladies now bedeck their champions with less poetical but more practical and healthier scarves. We live no longer in the ancient days of helm and harness and of warring knights but in the peaceful, honest bourgeois days of under jackets and warm bandages; that is, no longer in the Iron Age but that of flannel—flannel everywhere. It is, in fact, the best cuirass against cholera, our most cruel enemy. I myself am up to my neck in flannel and consider myself cholera-proof. The king himself wears now a belt of the best bourgeois flannel.

Many disguised priests are now gliding and sliding here and there among the people, persuading them that a rosary that has been consecrated is a perfect preservative against cholera. The Saint-Simonians regard it as an advantage of their religion that none of their number can die of the prevailing malady, because progress is a law of nature, and as social progress is specially in Saint-Simonianism, so long as the number of its apostles is incomplete none of its followers can die. The Bonapartists declare that if anyone feels in himself the symptoms of cholera, if he will raise his eyes to the column of the Place Vendôme he shall be saved and live. And so has every man his special faith in these troubled times. As for me, I believe in flannel. Good dieting can do no harm, but one should not eat too little, as do certain persons who mistake pangs of hunger felt in the night for premonitory symptoms of cholera. It is amusing to see the poltroonery many manifest at table, regarding with defiance or suspicion the most philanthropic and benevolent dishes and swallowing every dainty with a sigh.

The doctors told us to have no fear and avoid irritation; but they feared lest they might be unguardedly irritated, and then were irritated at themselves for being afraid. Now they are love itself, and often use the words Mon Dieu! and their voices are as soft and low as those of ladies lately brought to bed. Also they smell like perambulating apothecary shops, often feel their stomachs, and ask every hour how many have died. But as no one ever knew the exact number, or rather as there was a general suspicion of the exactitude of the figures given, all minds were seized with vague terror, and the extent of the malady was magnified beyond limits. In fact, the journals have since published that on one day, the 10th of April, two thousand people died. But the people would not be deceived by any such official statement, and continually complained that far more died than were accounted for. My barber told me how an old woman sat at her window a whole night on the Faubourg-Montmartre to count the corpses that were carried by, and she counted three hundred; but when morning came she was chilled with frost, and felt the cramp of cholera, and soon died herself. Wherever one looked in the streets, there he saw funerals or, sadder still, hearses with no one following. But as there were not hearses sufficient, all kinds of vehicles were used, which, when covered with black stuffs, looked very strange. Even these were at last wanting, and I saw coffins carried in hackney coaches. It was most disagreeable to see the great furniture wagons used for “moving” now moving about as dead men’s omnibuses, or omnibus mortuis, going from house to house for fares and carrying them by dozens to the field of rest.

The neighborhood of a cemetery where many funerals were held presented the most dispiriting scene. Wishing to visit a friend one day, I arrived just as they were placing his corpse in the hearse. Then the sad fancy seized me to return the call he had last made, so I took a coach and accompanied him to Père Lachaise. Having arrived in the neighborhood of the cemetery, my coachman stopped, and awaking from my reverie, I could see nothing but literally sky and coffins. I was among several hundred vehicles bearing the dead, which formed a queue or train before the narrow gate, and as I could not escape, I was obliged to pass several hours among these gloomy surroundings. Out of ennui, I asked my coachman the name of my neighbor corpse, and—woe the chance!—he named a young lady whose coach had, some months before, as I was going to a ball at Lointier, been crowded against mine and delayed just as it was today. There was only this difference, that then she often put out of the window her little head, decked with flowers, her lovely, lively face lit by the moon, and manifested the most charming vexation and impatience at the delay. Now she was quite still, and probably very blue; but ever and anon, when the mourning horses of the hearses stamped and grew unruly, it seemed to me as if the dead themselves were growing impatient and, tired of waiting, were in a hurry to get into their graves; and when, at the cemetery gate, one coachman tried to get before another, and there was disorder in the queue, then the gendarmes came in with bare sabers; here and there were cries and curses, some vehicles were overturned, coffins rolling out burst open, and I seemed to see that most horrible of all émeutes—a riot of the dead.

To spare the feelings of my readers, I will not further describe what I saw at Père Lachaise. Hardened as I am, I could not help yielding to the deepest horror. One may learn by deathbeds how to die, and then await death with calmness, but to learn how to be buried in graves of quicklime, among cholera corpses, is beyond my power. I hastened to the highest hill of the cemetery, where one may see the city spread out in all its beauty. The sun was setting; its last rays seemed to bid me a sad goodbye; twilight vapors covered sick Paris as with a light white shroud, and I wept bitterly over the unhappy city, the city of freedom, of inspiration and of martyrdom, the savior city that has already suffered so much for the temporal deliverance of humanity.

Read the other entries in our series: George Eliot, Samuel Pepys, Willa Cather, Lucretius, Thomas Mann, Jack London, John Keats, Alessandro Manzoni, Giovanni Boccaccio, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Daniel Defoe, François Rabelais, and Robert Louis Stevenson.