The pens at Ellis Island, c. 1902. Photograph by Edwin Levick. The New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

The notion that new, young immigrants bring drugs, crimes, and rape to our shores isn’t a new one. After nine Italian Americans were lynched in New Orleans in 1891, a New York Times editorial referred to the “mob’s victims” as “desperate ruffians and murderers…sneaking and cowardly Sicilians, the descendants of bandits and assassins who have transported to this country the lawless passions, the cutthroat practices, and the oath-bound societies of their native country.” In 1920, a congressional committee assembled to curtail migration asserted, “It simply amounts to unrestricted and indiscriminate dumping into this country of people of every character and description,” speaking largely about incoming Jews from Europe. A Cornish journalist wrote in 1842 that the Irish who land in New York “are not only ignorant and poor, but they are drunken, dirty, indolent, and riotous, so as to be objects of dislike and fear to all in whose neighborhood they congregate in large numbers.”

Today, President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have made much of the threat of young immigrants from El Salvador, calling them “wolves in sheep’s clothing” and asserting that the MS-13 gang has “transformed peaceful parks and beautiful, quiet neighborhoods into bloodstained killing fields.” Each new group of immigrants to this country brings a new brand of scorn.

The nineteenth century saw a substantial migration boom: first, most notably, the Irish in the early part of the century, and then the Italians. In 1850, a little more than two million immigrants resided in the United States. By 1930 that number had spiked to over fourteen million. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese immigrants were landing in California, and millions of Germans were coming through Ellis Island headed largely for the country’s interior. Immigrants of dozens more nationalities came to the United States for the reasons they always have: leaving trouble at home, searching for a better life on these fabled shores. The majority of Italians and Irish stayed along the eastern seaboard, finding what lodging they could in tenements—too tall buildings with little structural integrity or municipal oversight, comprised of squalid apartments for which landlords charged predatory rents, and where, as multiple families crammed into tiny quarters, disease and poverty festered. In How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890, Dutch American Jacob Riis provided a painstaking catalogue of the conditions of New York’s tenements and moralized upon the vast inequality of the metropolis and of the nation. “The tenements today are New York,” wrote Riis, “harboring three-fourths of its population. When another generation shall have doubled the census of our city, and to that vast army of workers, held captive by poverty, the very name of home shall be as a bitter mockery, what will the harvest be?”

One consequence of tenement life was, unsurprisingly, criminal activity: gangs.

Looking back, the rise of the nineteenth century’s gangs is easy to parse. Poverty and disenfranchisement of young immigrants, combined with the rampant xenophobia ignited by a sudden uptick in immigration, led not only to isolated criminal actions (pickpocketing, robbery, the kind of crime that comes from despair), but to organized criminal groups. The gangs of late nineteenth-century New York—the infamous Irish Mob, the Bowery Boys, and the Five Points Gang—were made up largely of young immigrant and first-generation Italian, Irish, and Jewish kids. These ragtag criminal organizations ruled the streets and grew rapidly. They weren’t just providing new recruits an economy and material survival, though those were clear benefits of involvement. Perhaps more importantly, they were offering something grander that hard-knock tenement life in a new, unyielding land had stripped away: a sense of belonging, of agency, and of brotherhood.

Throughout history, young men of all colors and creeds who have been stripped of agency, and with grim prospects for their future, have found and even created parallel systems of identity and economy. These groups provide a feeling of success and upward mobility for those who are not offered the same in mainstream society.

All over the world, gangs recruit members from downtrodden circumstances—poor kids, orphans, victims of abusive families—preying off their marginalized status and lack of other options. In El Salvador, where I have spent much time reporting, gangs like MS-13 and Barrio 18 grow their ranks by force, in the same way armies recruit child soldiers. But they also lure kids in with the promise of a better life, offering not so much money—most gang members in El Salvador in fact make very little money, hardly more than enough to buy food and the occasional pair of shoes—but basic survival. Gangs often start merely as groups of neighbors or friends from similar social circumstances, like they did in the tenements. When joined in opposition to the same perceived enemy—which could be the state, the cops, a rival friend group, another neighborhood gang—these groups offer both protection and a sense of purpose.

“I needed money,” a young woman, a former gangster, told me in a jail outside of San Salvador, while licking an ice cream cone.

“It was a real friendship,” another girl told me of her relationship to the local gangsters. Her choices were at least in part forced by her circumstances, but also, she’d wanted to belong.

As a Salvadoran gang leader told the New York Times this fall, “What does our existence say about the government and the services it fails to provide? We exist because there is nothing else.” It’s no different in the United States. Once the American dream begins to feel like a sham where there are no bootstraps on which to yank, young people opt not to play a rigged game. It should be noted that there is no widely agreed-upon definition of a gang, which speaks to both the pervasiveness of criminal activity among disenfranchised youth and the myriad manifestations.

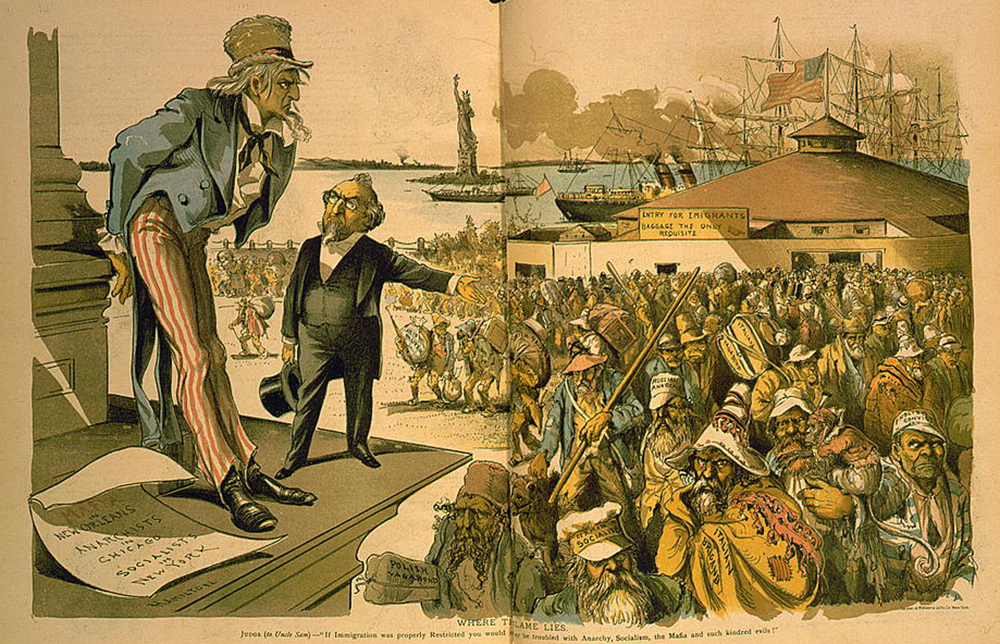

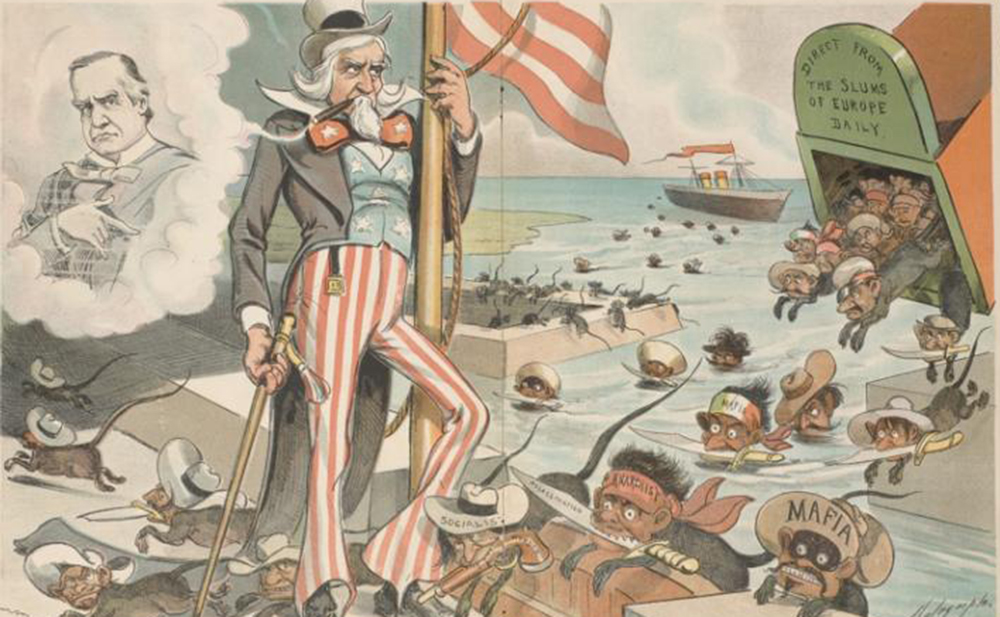

Gangs of immigrant descent, from MS-13 to the Bowery Boys, incite further xenophobia, and reify preexisting fears about immigrants. In the nineteenth century the nativist Know-Nothing Party—an isolationist, anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic group that is all too similar to today’s far-right groups—sprang up to guard the nation’s purity and limit immigration, and soared in popularity. Political cartoons maligning immigrants as thugs, thieves, and subhumans abounded: one depicted a horde of Irishmen as drunken apes assaulting police officers, another shows Uncle Sam being devoured by demonic newcomers, another shows mustachioed Italians passing an “afternoon’s pleasant diversions” by attacking a defenseless young man with a knife.

Even more mainstream publications propagated highly anti-immigrant sentiments, which were a response to real and perceived crime among young immigrants. A poem published in a 1892 issue of The Atlantic reads, “Wide Open and unguarded stand our gates, / And through time presses a wild motley throng.” The throng carries “the Old World’s poverty and scorn,” speaks in “accents of menace, alien to our air, / Voices that once the Tower of Babel knew!” In the 1920s, Congress passed acts limiting the immigration of Italians, in response to the infamy of the growing mafia and the widely held belief that Italians would bring further crime to the United States.

While MS-13 has taken center stage in our national discourse, the criminal groups of yore have become legend, cult figures, thrilling antiheroes. A gang is nothing if not fundamentally American; consider the outlaws of the West, the pioneers (those decimating forces), the bands of stagecoach robbers, the mob, all deeply embedded in American consciousness. We now glorify yesterday’s outlaw cultures—see Gangs of New York, Deadwood—while continuing to vilify the newest outlaws and insist that, if not barred from entering our country, they will be our nation’s downfall. Race and who is considered a minority outsider have something to do with it. The Italian and Irish Americans who were once kept out of country clubs and barred from entering the country in too large numbers are no longer ill-considered minorities in the U.S. but, rather, part of the white majority. The cycle of excluding, marginalizing, and vilifying the newest groups of young immigrants continues with a retrograde abandon and scorn. We move predictably on to other targets of darker skin.

As much as “bad immigrants” are endlessly covered in the press, their eventual and invisibly slow conscription into the war against outsiders is a pervasive, if hardly remarked upon, phenomenon. Once the slandered immigrants of yesterday have been brought into the folds of today’s white majority, society turns them into heroes and finds new bad guys to take their place. For those of us from white immigrant or “model minority” backgrounds, it’s easy to succumb to historic amnesia, forgetting that we, too, were once the maligned newcomer.

Since Trump took office, he and members of his administration have succeeded in making MS-13 all but a household name. MS-13 was born in Los Angeles during the 1980s among disaffected young men fleeing the country’s civil war (one the United States helped back by providing funding, training, and arms to a government that perpetrated mass atrocities) who banded together as a protective force against other neighborhood gangs in their low-income neighborhoods, settings that mirrored the tenements of the nineteenth century. Many of these young, traumatized men were arrested, then deported back to El Salvador, bringing with them the gang culture and identity. Today MS-13, an unintended consequence of both U.S. foreign policy and U.S. immigration policy in the 1980s and 1990s, has asserted a stranglehold upon many communities in El Salvador and other Central American countries.

In the United States, its numbers also seem to be growing (though not to the degree that the current administration would like us to think). In his January 2018 State of the Union address, Trump doubled down on the attack on MS-13 and, by extension, on young Central American immigrants, claiming that these murderous young people were taking advantage of immigration “loopholes” to bring their homicidal violence into the United States by design. “Tonight, I am calling on the Congress to finally close the deadly loopholes that have allowed MS-13, and other criminals, to break into our country,” he said.

This speech demonstrated no comprehension of the United States’ role in MS-13’s creation. Trump’s words served not only to criminalize young immigrants with a broad brush but also to function effectively as a PR campaign for MS-13, painting them as the biggest, baddest bunch of boys around—the image MS-13 hopes to propagate. Gangs, as scholars note, form and gain strength in part through their relationship to a common enemy.

The current administration’s view—which echoes much of America’s views—on MS-13 as an outsider, predatory force storming our gates reflects a long-standing myth about immigrant gangs in our country: that these gang members are fundamentally depraved human beings, with a moral composition that is contrary to American values. In this worldview, gangs—from the Bowery Boys to Chinese gangs like the Flying Dragons—are a fundamental threat to society, rather than inevitable perversions of an unequal society that has failed.

In 2014, when the population of young, unaccompanied central Americans had—largely on account of gang violence back home—so suddenly spiked, the government’s infrastructure for apprehending and detaining them burst at the seams, and this cycle of maligning began anew. In the imagination of the nation’s self-assumed protectors, these kids were bringing disease and crime with them across the border. They were sucking our resources dry. On Long Island, where thousands of them were temporarily released while they fought their deportation cases, these youth were routinely blocked from registering for school, supposedly because of complications related to proving their residency. Yet other communities throughout the country didn’t have such issues getting young people into school. The message to these new youth on Long Island was clear: they weren’t welcome. Today one of MS-13’s strongest presences in the country is on Long Island.

“If it shall appear that the sufferings and the sins of the ‘other half’ and the evil they breed,” wrote Riis in his 1890 book, “are but as a just punishment upon the community that gave it no other choice, it will be because that is the truth.”