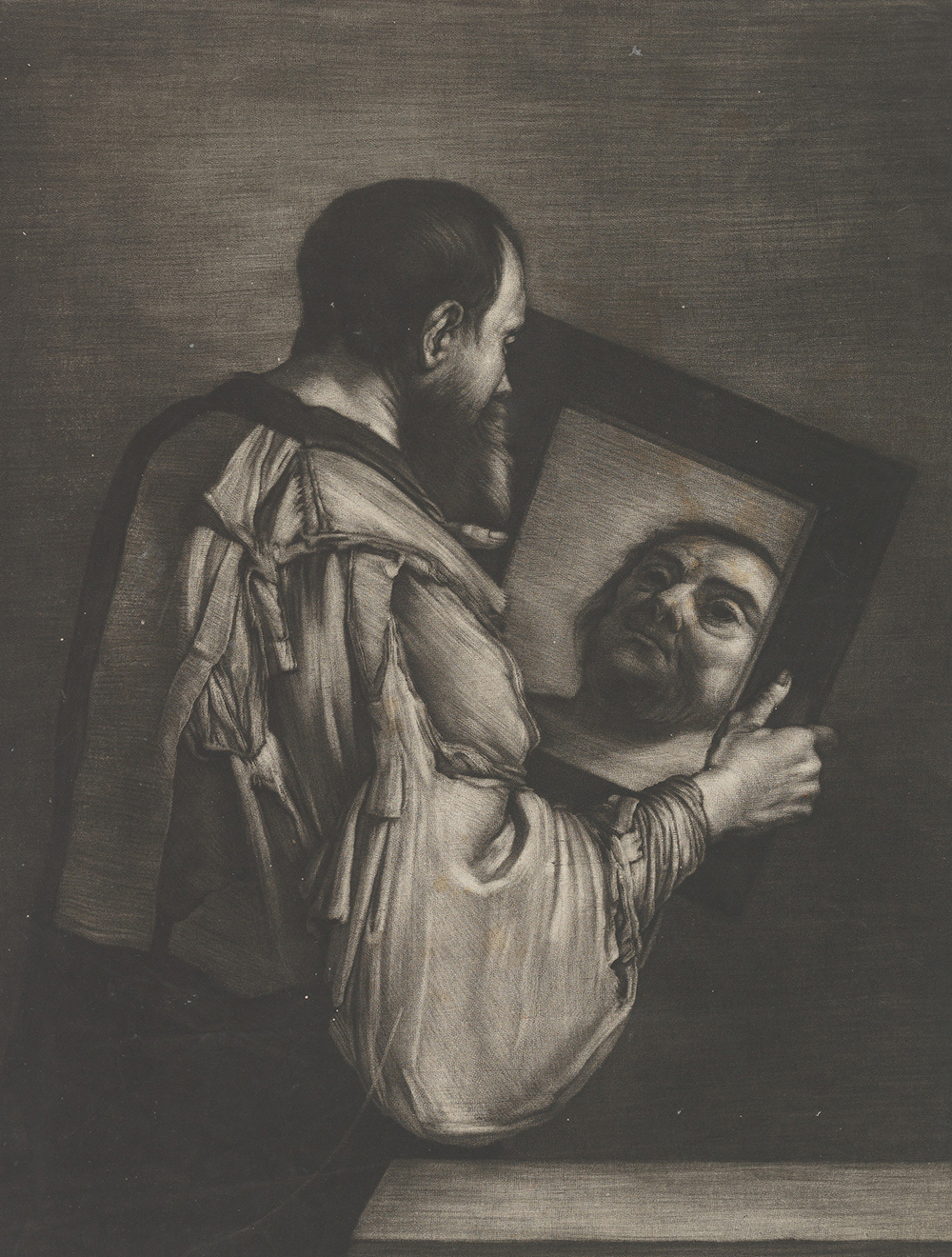

The Death of Socrates, by Jacques Louis David, 1787. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1931.

Bested only by Jesus, Socrates is the most celebrated of the West’s condemned men. His story is familiar to readers of Plato’s Apology, an account of Socrates’ self-defense at his 399 BC trial, and to viewers of Jacques-Louis David’s 1787 painting La Mort de Socrate: the Athenian gadfly was found guilty of corrupting the city’s young and straying from its approved theologies, crimes that earned him not a cross to bear but a cup to drink. But less familiar than these two forensic episodes—his courtroom sentencing and execution by hemlock about a month later—are the events that come between them.

This intervening time is the backdrop for Plato’s Crito, which stages Socrates’ captivity in prison and an opportunity for his escape. Crito, the anxious friend for whom Plato’s dialogue is named, visits Socrates in his cell and urges him to flee to a life of exile in Thessaly, where Crito claims to have friends who would shelter Socrates. “What you are doing doesn’t seem right to me,” Crito says, “giving yourself up when you could have been saved.” Execution, he continues, would leave Socrates’ children orphans and would rob Athens of one of its sharpest minds. Crito, himself a wealthy Athenian aristocrat, even argues that not using his riches and influence to save Socrates would bring about the “most shameful reputation, that [he] would seem to value money above friends.”

Despite Crito’s practical and moral appeals, however, Socrates elects to remain in his prison cell and die. Why does history’s paragon of free thinking, always suspicious of widespread belief, defer to his city’s laws in this time of crisis? Why would Plato turn his gadfly into a sheep, willingly yielding to its own demise?

Socrates’ decision to face execution rather than escape likely strikes modern readers as a particularly odd and even foolish choice when viewed through the lens of political liberalism. As one of the fundamental principles of his 1651 Leviathan—to take one example of such thinking—Thomas Hobbes cites every man’s “right of nature,” namely the “liberty each man hath to use his own power as he will himself for the preservation of his own nature; that is to say, of his own life.” Centuries after Hobbes’ treatment of man’s inviolable right to self-preservation, Martin Luther King Jr. cites Socrates in his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” as part of his discussion of unjust laws and the moral soundness of principled defiance in the face of them. “Academic freedom,” King explains, “is a reality today because Socrates practiced civil disobedience.”

King’s entangling of academic freedom and civil disobedience can help us understand why Socrates decides not to flee his prison cell despite his willingness to reject the state’s orders elsewhere. In the Apology, for example, Socrates makes explicit his preference for philosophical inquiry over the “unexamined life,” and in response to a proposed acquittal on the condition that he cease his characteristic prodding, Socrates reveals an impulse for defiance:

I am more obedient to the god than to you, and so long as I am able I will not cease seeking wisdom and appealing and demonstrating to every one of you I come across, saying my customary things: “Best of men, you are an Athenian, of the greatest and most renowned city in regard to wisdom and power. Are you not ashamed that you care about how you will acquire as much money as possible, and reputation and honor, while you do not care or worry about wisdom and truth and how your soul might be as good as possible?”

By refusing to preserve a non-philosophizing existence, Socrates sketches the limits of any Hobbesian instinct for self-preservation he may have. If we are to believe Socrates’ logic in the Apology, he values inquiry over life, academic freedom over political security.

This absolute allegiance to philosophical questioning is unsurprising to readers of other Platonic dialogues, which feature Socrates challenging others’ assertions and leading them into unforeseen conclusions. In Plato’s Republic, for instance, Socrates dismantles Thrasymachus’ claim that justice is merely “the advantage of the stronger,” and in the Meno Socrates guides an uneducated slave toward complex geometric proofs. Texts like these show Socrates first and foremost as an intellectual “midwife”—a metaphor he himself uses in the Theaetetus—who helps his interlocutors bring forth from their souls, often with great difficulty, philosophical truths.

In the Crito, too, one finds Socrates devoted to the mission of academic midwifery. Early in the dialogue, he remarks that he is “the sort of person who is persuaded in my soul by nothing other than the argument which seems best to me upon reflection.” The argument at hand, it turns out, concerns a personal matter for Socrates: “whether it is just or unjust for me to try to leave here, when I was not acquitted by the Athenians.” The Crito’s first pages, not unlike Plato’s other works, show Socrates both dissuading Crito from deferring to widespread opinion as well as advocating the salutary effects of just behavior. Socrates asks his friend whether they agree that “acting unjustly is evil and shameful in every way for the person who does it.” “We do,” Crito admits.

Pushing the argument one step further, Socrates asks, “By leaving here without persuading the city, are we doing someone harm, and those whom we should least of all harm, or not?” One might imagine that Plato could have ended the dialogue here, showing Crito convinced that an unjust prison break is “shameful” and even “harmful.” Crito, however, hesitates: “I’m unable to answer what you’re asking, Socrates; I don’t know.”

The second half of the dialogue, launching from this moment of hesitation, strays from the standard Platonic model by introducing an unconventional interlocutor. Unlike other works that showcase Socrates sparring with his Athenian contemporaries, he spends the rest of the Crito describing a hypothetical argument pitting himself against a personification of the Laws of Athens, a rhetorical strategy that allows him to explain his decision to Crito. Imagining how the Laws might approach him as he ponders his escape from prison, Socrates ventriloquizes the Athenian legal code, formidable in their authority and “standing over us,” perhaps like a parent who has caught a child on the precipice of disobedience: “Tell me, Socrates, what are you intending to do?”

No mere caricature of a disciplinarian, Socrates’ Laws prove to be an interlocutor even the gadfly himself cannot outwit. The Laws, who speak only through this hypothetical conversation, concern themselves with the earlier question of whether leaving the city constitutes a kind of harm. They draw Socrates back to one of his fundamental ethical principles—which also appears in the first books of the Republic—that “neither to do wrong or to return a wrong is ever right, not even to injure in return for an injury received.”

Taking up this maxim against intentional injury, even injury that one might call justified vengeance, the Athenian Laws continue:

By attempting [to flee from prison], aren’t you planning to do nothing other than destroy us, the laws, and the civic community, as much as you can? Or does it seem possible to you that any city where the verdicts reached have no force but are made powerless and corrupted by private citizens could continue to exist and not be in ruins?

Socrates’ escape, they argue, would not simply be an act of clandestine civil disobedience; it would amount to destruction of the Laws themselves. And since his own salvation would injure another—namely, this fictive interlocutor—Socrates must therefore decline Crito’s offer of escape.

In their argument, the Laws suggest that one harms a legal code not only by enacting corrupt statutes or by straying from abstract ethical norms like justice or universal human rights. Citizens injure the civic community when they disregard verdicts, rendering them “powerless and corrupted,” and by obeying them only when convenient. If a city adopts a selective allegiance to the rule of law—perhaps by making exceptions for unique figures like Socrates or by allowing influential aristocrats like Crito to smuggle Socrates to freedom—it exchanges dependable legal principle for fickle opportunism.

As part of their rejection of Socrates’ flight, the Laws present an early theory of social contracts over two thousand years before the writings of John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. If Socrates were to evade the consequences of the city’s guilty verdict, the Laws explain, he would renege on his long-standing agreement with Athens to live according to its rules: “Socrates, did we agree on this, we and you, to honor the decisions that the city makes?” The Laws propose that Socrates’ continued residence in Athens amounts to his active assent to this covenant. “Did you choose us and agree to be governed by us?” they ask. “Aren’t you going against your contract and agreement with us ourselves, which you were not forced to agree to?”

If he were to break this contract—only reaping the city’s benefits while dodging its demands—Socrates would harm Athens and, perhaps even more regrettably, would have to take refuge in other cities that tolerate a self-serving citizenry. Plato’s Crito suggests that leaving a city governed by the rule of law for one in which self-interested disobedience is the norm could never be a sensible choice for this wisdom-loving philosopher:

Will you flee from well-governed cities and from the most civilized people? Is it worth it to you to live like this? Will you associate with them, Socrates, and feel no shame when talking with them? What will you say, Socrates—what you said here, that virtue and justice are most valuable for humans and lawfulness and the laws?

By fleeing to a place with “plenty of disorder,” Socrates would injure both the Laws of Athens and his own well-being. In this corrupt city of exiles, he would find those who delight in disobedience, who “might listen with pleasure to you, about how you amusingly ran away from prison wearing some costume or a peasant’s vest,” making a slapstick mockery of Athenian lawfulness. The Crito asks if it is “worth it” to live among such debased citizens, and by staying in prison Socrates provides an answer: living among irreverent chaos is worse than dying under the rule of law.

We might, then, view the Crito less as a paean to legal submissiveness and more as a defense of uncompromising free inquiry, even inquiry that persuades one to die. Dying, Socrates hypothesizes in the last paragraphs of the Apology, is a “migration” to an underworld filled with the thinkers and heroes of the past, where “it would be indescribably marvelous to debate and pass the time.” If nothing else, Socrates quips, “I should certainly hope that the people there would not put someone to death” for philosophical discussion. If Socrates must choose between an academic paradise in Hades and an “unexamined life” of disorder and cynicism in the world of the living, his might be a death worth dying.

Read more on legal debates in our Spring 2018 issue, Rule of Law.