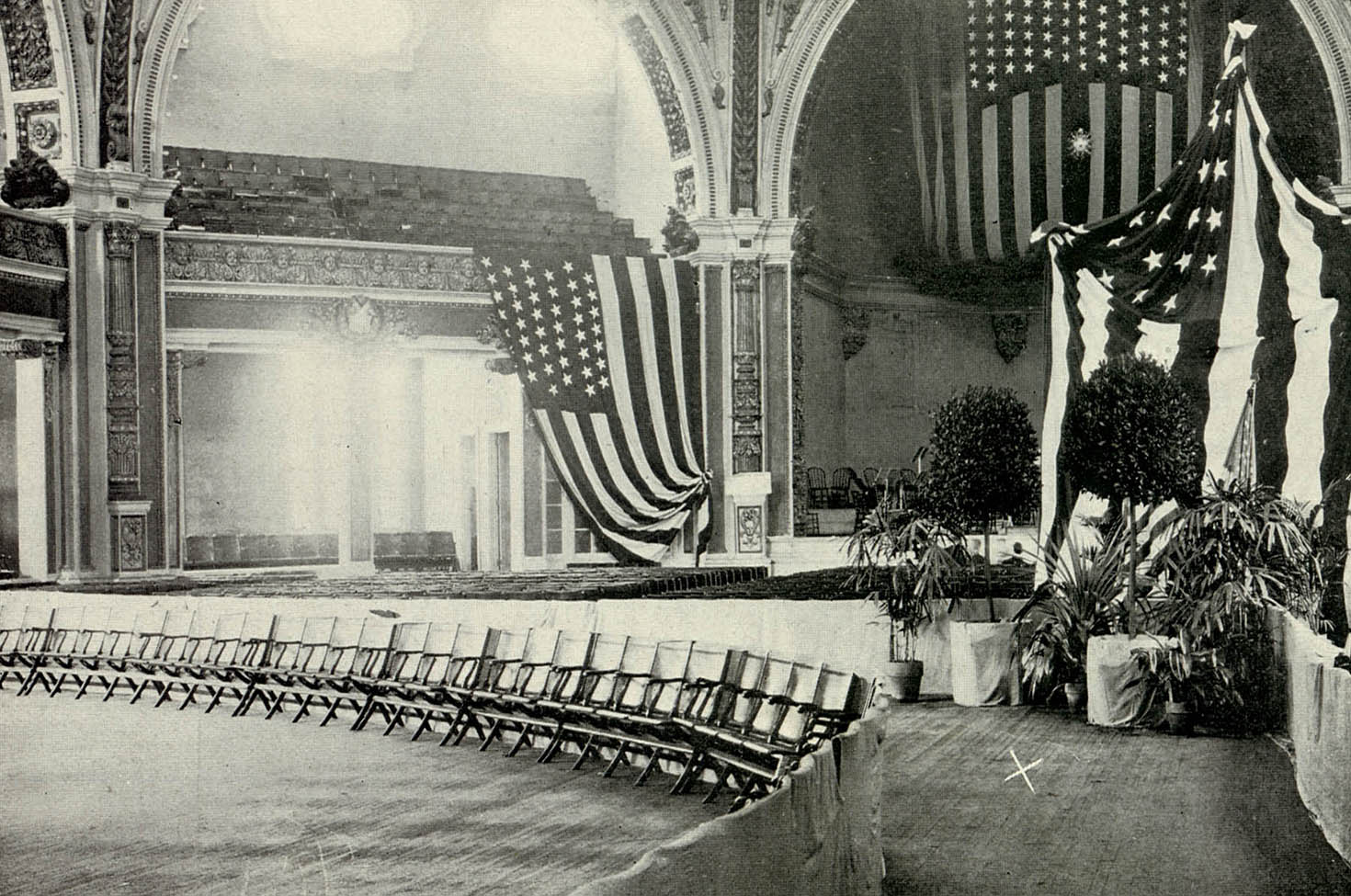

The Temple of Music inside the Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo, New York, September 6, 1901. Site of the shooting of President William McKinley marked with an x. Photograph by C.D. Arnold. Wikimedia Commons.

Leon Czolgosz hadn’t worked in years. When he arrived in Buffalo on the last day of August 1901, he rented a room above John Nowak’s saloon for two dollars a week. Czolgosz—slender, clean-shaven, brown-haired, blue-eyed, twenty-eight years old—survived mostly on milk and bread. He didn’t talk much. He didn’t stay long. He seemed to be one of those young men adrift in America’s raw, roaring economic churn. One afternoon, he walked to Walbridge Hardware on Main Street and bought the most expensive handgun on display, a .32 caliber Iver Johnson automatic revolver, for $4.50.

Czolgosz’s parents immigrated from Eastern Europe to the Midwest and then kept moving in search of work. His mother died when he was about ten. His stepmother seemed uncaring, his father distant. Czolgosz attended school when he could, worked a few hours here and there when he had to, and then, when he turned sixteen, followed his father’s instructions to get a full-time job. Five years in classrooms made him the best educated of his seven siblings. Czolgosz eventually ended up at the Cleveland Rolling Mill, a steel-wire factory with modern equipment and management. He could count on decent pay, steady hours, and tolerable physical demands. If all went well, Czolgosz might one day rise out of the working class.

Things didn’t go well. In 1893 America sank into a depression, businesses shut down, and people across the country lost their jobs. Czolgosz was among them. When he was rehired, the company engaged in a brutal price war that resulted in lower wages. After Czolgosz joined a strike, he was fired and put on a blacklist. The only way he could work again was to wait for a new foreman to come in and then reapply under a fake identity. He chose the name Fred Nieman: Fred Nobody.

Everyone around him could see that he was unhappy, brooding, almost broken. He had been set back, as so many others had, and couldn’t recover, and in this too he wasn’t alone. Then he stopped trying. In 1898 he told his boss that he was unwell and had to quit.

His family had purchased a fifty-five-acre farm—he had emptied his bank account to contribute—and it was there he took refuge. He tinkered in the barn but refused to help with the hard labor. He wouldn’t eat with his family when his stepmother was home and took herbal remedies for ailments he wouldn’t discuss. Reading the newspapers and Edward Bellamy’s bestselling utopian novel Looking Backward: 2000–1887 became preoccupying interests. Czolgosz called himself a socialist, sometimes an anarchist. In May 1901 he heard one of the most famous anarchists, Emma Goldman, speak in Cleveland and was so taken by her that he began to contemplate radical, violent, and, in his mind, heroic, action. First, though, he introduced himself. They exchanged a few words, and he made a good impression, but if he was expecting to be taken in, he would have been disappointed. All he came away with was a few books she recommended.

His family didn’t know what to make of him, and he did not seem to know what to make of himself either. “I never had much luck at anything, and this preyed upon me,” Czolgosz later said. “It made me morose and envious.” He desperately wanted to sell his share of the farm and leave his family behind. They gave him seventy dollars in July 1901, and he disappeared.

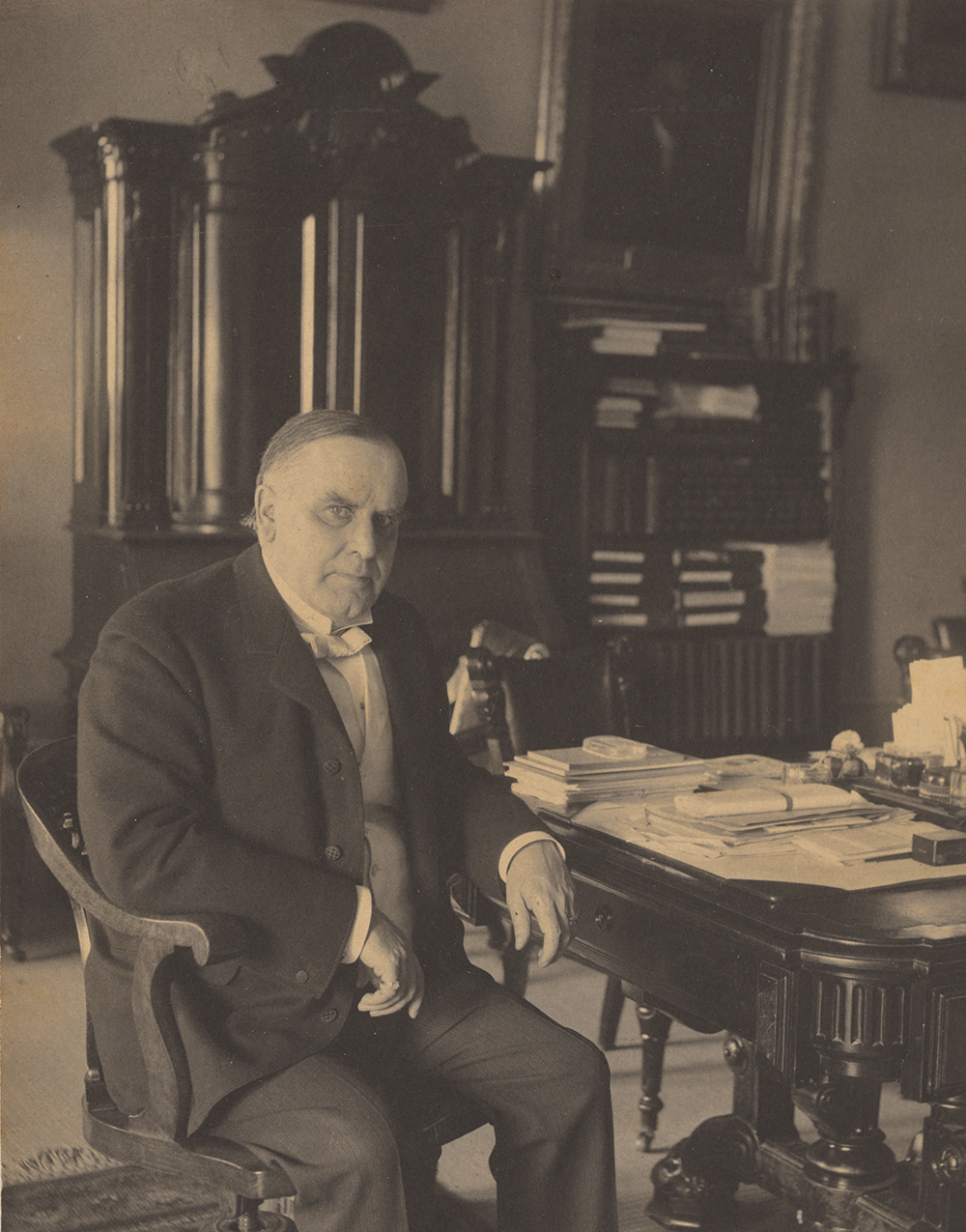

President William McKinley, well rested after a summer at home in Ohio, arrived in Buffalo on Wednesday, September 4, 1901, for the Pan-American Exposition. It was a monthslong festival in a 350-acre park meant to showcase America as a flourishing and innovative nation, taking its rightful place as a world leader. The Expo featured a Fountain of Abundance and a Tower of Light, and each evening hundreds of thousands of eight-watt lightbulbs illuminated the buildings, reflecting pools, and sculptures. It was the first massive display of electric power, generated by the alternating currents of nearby Niagara Falls. Inventors presented a new electric battery, a wireless telegraph, and a device called an akouphone that allowed the deaf to hear. A simulated trip to the moon on the spaceship Luna was so popular that afterward the creator patented the machine. Thomas Edison’s film company captured it all.

The showmen organized the fairground to reflect the achievements of a modern, industrial America—as they understood it. Visitors to the midway could watch reenacted battles between Native Americans and U.S. soldiers. Organizers had brought entire indigenous families to live in faux villages. “Darkest Africa” was enclosed by a fence; across from it was the “Old Plantation.” Only after activists, mostly black women, called on officials to do better, did the fair find room to display the books, art, and inventions of African Americans. “The Negro Exhibit” opened in a stifling convention center and received little attention from white journalists or the Expo’s promoters. Some of those on display resisted and a few others protested that it was wrong, or racist, to treat humans as specimens. To most of the crowd, though, it was all just a spectacle.

McKinley had campaigned as “The Advance Agent of Prosperity” and often celebrated the country’s good fortune. He was fifty-eight years old, charming and generous even to critics, a gracious envoy to the business class who was still considerate of other opinions. He had been easily reelected in 1900. His vice president for his second term was Theodore Roosevelt, who was young and energetic and popular with voters because he didn’t seem beholden to the rich. Born into New York’s privileged set, Roosevelt had become a civil-service reformer, then a Rough Rider cavalryman in the Spanish-American War, then a crusading governor. The Republican establishment barely tolerated him. The vice presidency was supposed to diminish Roosevelt’s power and keep him out of sight.

On McKinley’s final day at the Expo, September 6, he planned to greet anyone who cared to meet him at the Temple of Music, an ornate domed building that could hold two thousand people. Many more than that were waiting outside late Friday afternoon.

The weather was humid and heavy, and many in the queue held handkerchiefs and dabbed at their brows. Within the Temple, a musician played a Bach sonata on one of the country’s largest organs as McKinley entered through a back door. He noted how cool it was inside. He seemed eager. “Let them come,” he said.

Attendants opened the front doors. National Guard soldiers paced in front of the entrance, and Secret Service agents and local police hovered. But no one noticed Czolgosz.

He had arrived at the Temple hours earlier and was near the front of the crowd, inconspicuous in his pressed gray suit, flannel shirt, and black string tie. “He appeared as a mechanic, a printer, a shipping clerk,” an eyewitness noted later. Except for one detail: he had wrapped his right hand with a plain handkerchief, as if he were injured. Underneath he gripped his revolver.

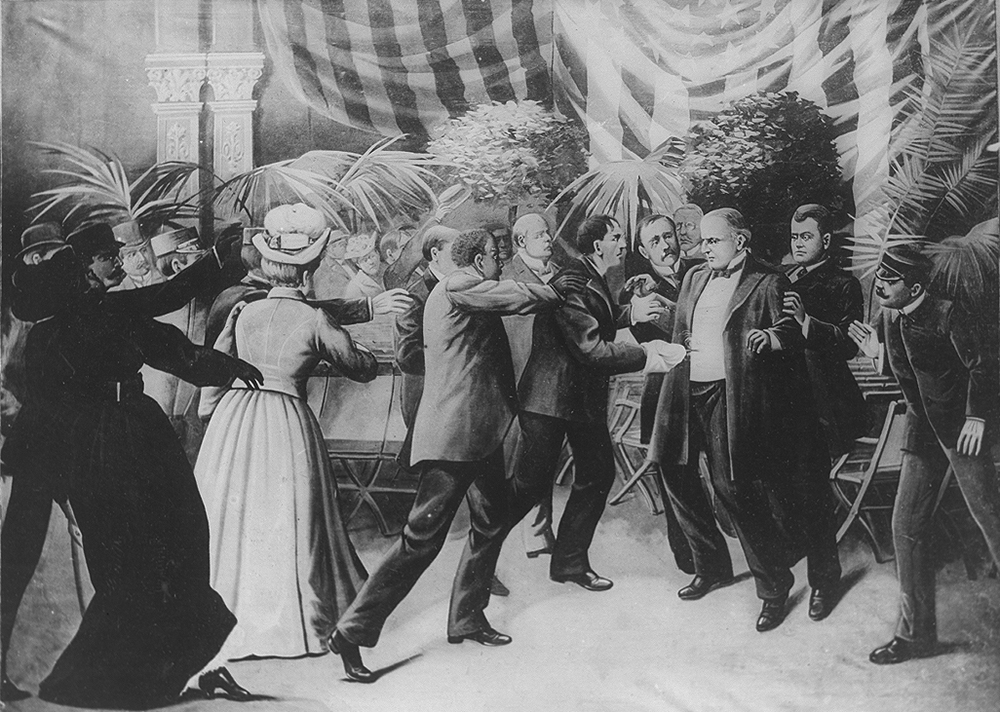

McKinley smiled and reached to shake Czolgosz’s left hand. As Czolgosz stepped forward, he raised his right instead and fired two bullets. The first grazed the president, but the second went deep into his abdomen, puncturing his pancreas and kidney and embedding somewhere beyond.

McKinley staggered, and was eased onto a chair by those near him. The man waiting behind Czolgosz—James Parker, an African American former constable from Georgia, now a waiter at an Expo restaurant—tackled him. Someone, a Secret Service agent or a soldier, grabbed the gun. In the melee it was hard to know who.

“I done my duty,” Czolgosz said as the police and soldiers and men waiting in line hit and kicked him. Czolgosz was blood-spattered and unmoving. McKinley was half conscious. “Be easy with him, boys,” he murmured. The police had to carry Czolgosz out before he was killed.

The president poked his fingers under his shirt. They came out bloody.

McKinley was put under the influence of ether by 5:20. Nine minutes later, the surgeon made his first cut. The team that operated on the president faced some challenges. Electricity brightened attractions throughout the Expo but not the hospital. A doctor used a mirror to reflect the rays of the setting sun onto the operating table until someone could hook up a light. The hospital was well equipped to treat any minor health problem—over the summer the most common complaints had been digestive troubles and toothaches—but no one expected a retractor would be required for a life-threatening injury. “The greatest difficulty was the great size of President McKinley’s abdomen and the amount of fat present,” the surgeon later noted. He first inserted a finger and then his entire hand but couldn’t find the second bullet. He cleaned the wounds, stitched them up, and sent a still unconscious McKinley to the home of John Milburn, the president of the Expo, to recover.

Before long, the president’s condition seemed to improve. Doctors allowed only his wife, Ida, to see him, but provided regular reports. His mind was clear. He was resting well. He took a teaspoon of beef juice every hour. Then three. He had a few drops of whiskey and jokingly asked to smoke a cigar. Doctors considered using one of Edison’s new X-ray machines to help locate the second bullet and recruited another doctor, whose height, weight, and fifty-six-inch girth matched the president’s, to serve as a test subject. But they never tried out the X-ray on McKinley.

Two days after the shooting, doctors reported that the president was past the danger point.

Then, before daylight on Friday, September 13, McKinley’s heart began failing. His pulse slowed. He could no longer eat. He became disoriented. Stimulants had no effect. Oxygen didn’t help. Gangrene had developed along the path of the bullet, and he was in septic shock. A flock of crows flying over the Milburn house had to be a bad omen. The doctors’ bulletin came at six thirty that evening: “The end is only a question of time.”

At ten Ida held her husband’s hand, then left his bedside. McKinley’s doctors discontinued the oxygen.

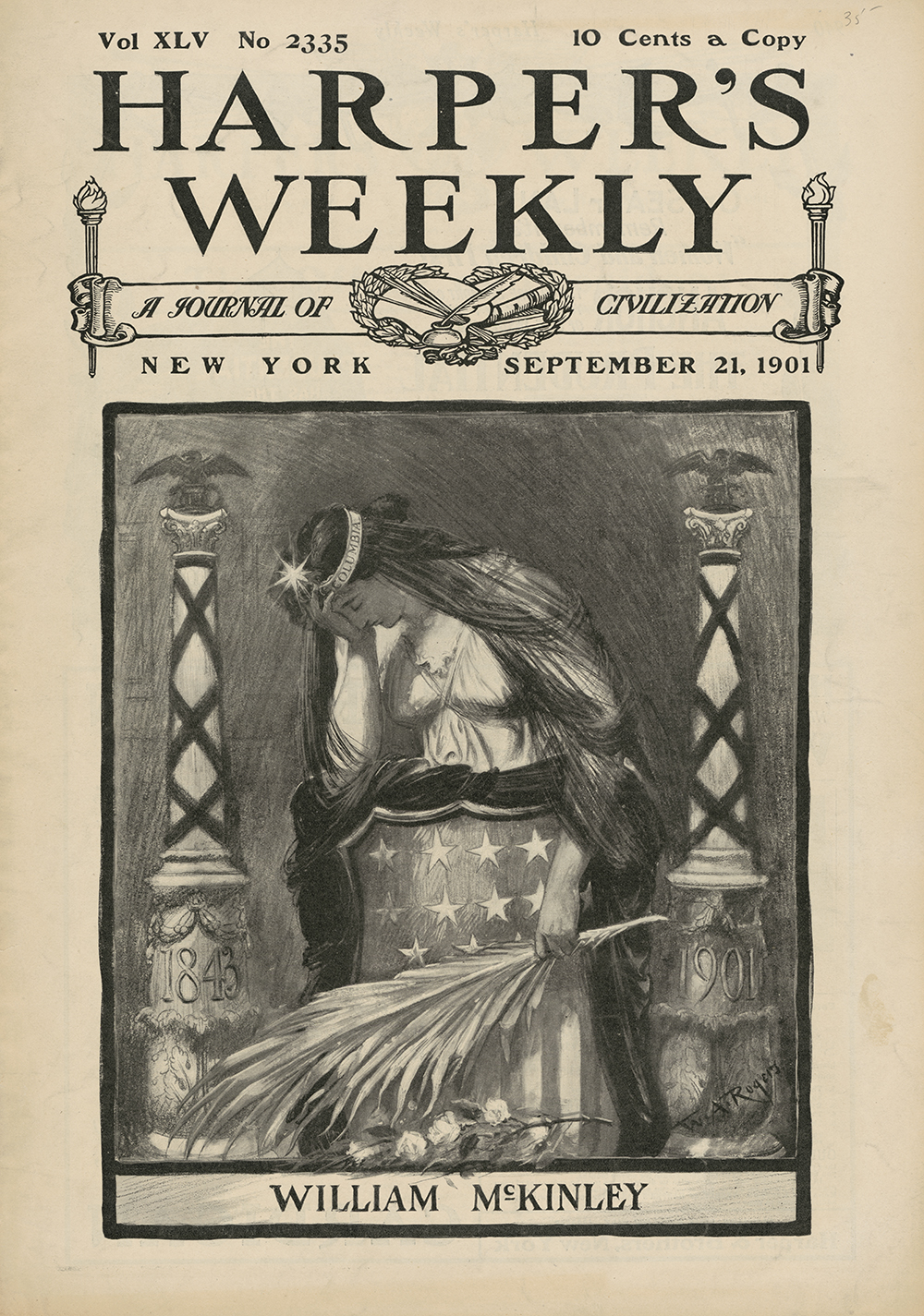

“The president died at 2:15 o’clock this morning.”

Czolgosz’s trial lasted barely two days. The jury deliberated for thirty minutes. On the morning of October 29, prison guards brought Czolgosz into the execution chamber. He was ashen, dressed in a gray shirt, prepared to speak his final words. “I shot the president because I thought it would help the working people and for the sake of the common people. I am not sorry for my crime,” he said. The guards tightened the straps on his head and chin. At twelve minutes past seven, 1,700 volts of electricity shocked the body of Leon Czolgosz.

He was buried in an unmarked grave. His corpse was dissolved in carbolic acid.

Adapted from The Hour of Fate: Theodore Roosevelt, J.P. Morgan, and the Battle to Transform American Capitalism by Susan Berfield by arrangement with Bloomsbury USA. Copyright © 2020 by Susan Berfield. Available from Bloomsbury.