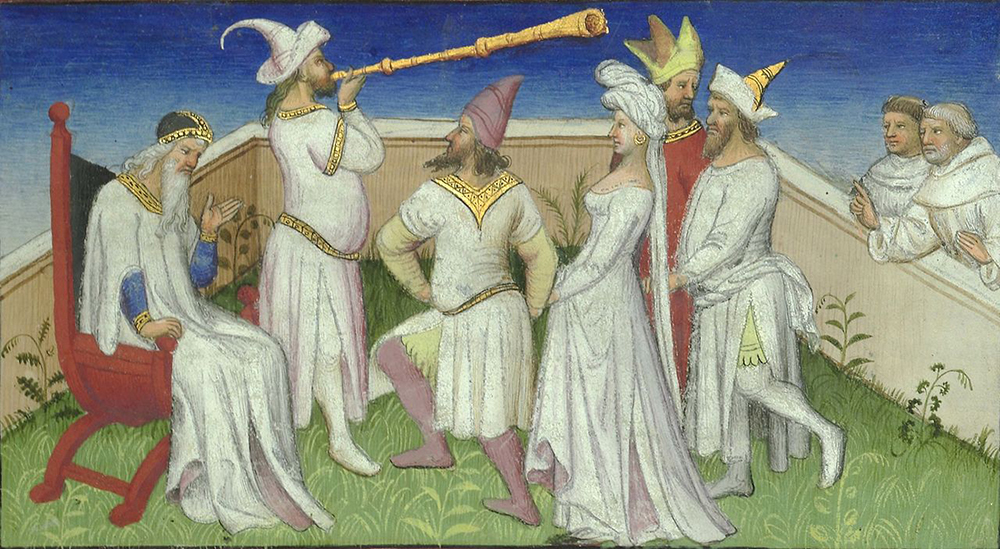

The Martyrdom of the Franciscans, by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, c. 1330. Photograph by Saliko. Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0).

There is a fresco in the Basilica di San Francesco, in Siena, that acts as a window into the imagination of men and women of the late Middle Ages. It depicts a scene of violence in faraway lands that is both gruesome and mesmerizing. Painted in the 1330s by one of the city’s most accomplished artists, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, it shows six members of the Franciscan Order dying at the hands of two executioners. Three of the friars have already been decapitated; the other three are about to follow suit. The Martyrdom of the Franciscans, painted on the walls of the chapter room of Saint Francis, has an elaborate structure that allows the action to unfold in a dynamic way and with astounding narrative richness. The top is occupied by a group of statues representing the cardinal sins, three on each side and one in the middle; the one in the center, separate from the rest, is Envy, the devil’s favorite vice. Underneath and perfectly aligned with Envy is the figure of the sultan as an incarnation of the most diabolical sin, followed immediately below by his politburo: five men on each of his sides, four on the first row and one behind, half-exposed. The group emulates the position of the statues of the sins.

The Franciscan friars occupy the lowest level. The three who have already been beheaded evince a strange correspondence with those of three children observing the scene. The other three friars, on the left, will die shortly. One of them, whose head is leaning toward us, is about to receive the fatal blow. Finally, the two bottom corners are dominated by the executioners. The witnesses on the left stare at the executioner, who is holding his sword and ready to strike. The ones on the right are leaving; over on that side, the show is already over. As it is clear from the clothing and the physiognomies of the witnesses and perpetrators of the killing, the scene takes place in the Far East, in the land of the Tartars.

Tartars. Under the umbrella of this demonym, premodern Europeans grouped a wide variety of human groups living in central Asia, from the Caspian Sea to Mongolia and China. In the late Middle Ages, their very name—reminiscent of Tartarus, the infernal regions of Greek and Roman mythology—was redolent of mystery, remoteness, and danger. The first eyewitness account of the Tartars by a Westerner comes to us from Brother Julian, a Hungarian Dominican who ventured across the Volga in the fourth decade of the thirteenth century. In a letter to the bishop of Perugia, Julian describes the palace of the khan (“so great that a thousand horsemen can enter through one gate”), expresses admiration for their ruthless warring techniques, and warns of their desire to conquer Hungary and even Rome. Upon his return from the East, in 1236 or 1237, Julian went to Rome to present his account to the pope. Also in 1237 Russian ambassadors traveled to the English court of Henry III in search of military assistance for their country, which had already been invaded and decimated by the Golden Horde, the army commanded by Batu, grandson of Genghis Khan. The ambassadors described Batu’s forces as “a detestable nation of Satan, to wit the countless army of the Tartars, broke loose from its mountain-environed home, and piercing the solid rocks [of the Caucasus] poured forth like devils from the Tartarus, so that they are rightly called Tartari or Tartarians…inhuman and beastly, rather monsters than men thirsting for and drinking blood, tearing and devouring the flesh of dogs and men…They are without human laws, know no comforts, are more ferocious than lions or bears.” In 1242 the Tartars did invade Hungary and Bohemia. A witness to the havoc wreaked by the invaders wrote that “it would be better not to be born than to fall in the hands of the Tartars.” Yet the horror, the fear, and the hysteria the Tartars invoked were also accompanied by curiosity.

In 1245 Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, a Franciscan friar, was dispatched to the Far East by Pope Innocent IV in an attempt to curtail the animosity of the Mongols by appealing to their mercy and goodwill—but also, more important, to gain intelligence about their customs, in particular their warring techniques and strategies, in case their armies were to reach Western Europe. By then, Mongol armies had already razed Russia, the south of Poland, and Hungary. Giovanni’s account of his travels, which came to be known as History of the Mongols, became an instant sensation in Italy. A Franciscan chronicler by the name of Salimbene di Adam noted that Giovanni “had written a big book about the deeds of the Tartars and other wonders of the world, and when people tired him with questions on the subject, he read it out loud, as I myself heard and saw on several occasions…The friars read his book in his presence and he interpreted and explained whatever seemed unclear.” His narrative includes a fascinating chronicle of the hardships of the journey to the camp of Genghis Khan’s grandson Güyük near Karakorum, in today’s Mongolia, where he witnessed Güyük’s crowning as Great Khan in the summer of 1246. The friar describes the new khan’s throne with unabashed admiration: “A lofty platform of boards had been erected on which the emperor’s throne was placed. The throne, which was of ivory, was wonderfully carved, and there was also gold on it, and precious stones, if I remember rightly, and pearls.” His account provides extensive information regarding the habits of the Tartars, including some colorful details about their cuisine. They ate pretty much anything: dogs, wolves, foxes, horses, “and if in need they even eat human flesh.”

Giovanni’s narrative falls in line with a growing interest in the wonders of the East, which was beginning to sweep through Europe at the same speed and with the same intensity as fear of the Tartars previously had. The East, exotic and dangerous, was becoming a “figure of aspiration and desire,” Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park write in their groundbreaking 1998 book Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750. The number of voyagers to the East increased, as did interest in the written accounts that followed their adventures. These publications circulated fast and widely; people were eager to learn more about the Tartars. Later in the thirteenth and especially in the fourteenth centuries, the accounts of travelers to the Far East would dominate the imagination of cultivated Europeans with a mixture of horror and wonder.

Perhaps no one contributed more to the modeling of this figure than the Genoese merchant Marco Polo. His chronicle, known informally as Il milione, started circulating in the last years of the thirteenth century and shaped the European imagination regarding Tartar habits, allure, and perils for decades. When the Tartars go on long expeditions through the steppe and run out of victuals, he writes, they resort to their horses: “Every rider pierces a vein of his horse and drinks the blood.” And when a khan dies, he writes, they carry his body to the mountain of Altai and kill everyone they encounter on the way, ordering their victims to “go and serve your lord in the next world.” Marco Polo seems particularly interested in another “strange custom” that has families celebrate weddings between dead children. He also dedicates a long, hyperbolic chapter to the palace (“the largest that was ever seen”) and the achievements of Kublai Khan (“the mightiest man in the world today”).

In addition to Giovanni’s History of the Mongols and Marco Polo’s Milione, there was Willem Van Ruysbroeck’s Journey to Mongolia, perhaps the most thorough and profound of these works. A Franciscan and an envoy of Louis IX of France, William visited the vast regions known as Tartary between 1252 and 1254. His keen eye gives us an invaluable account of the customs of the Mongols, their religion and cosmography, their multiethnic society, and their cuisine. Like the others, he expresses astonishment at the spectacular dimensions and luxury of the palace of the khan at Karakorum. But he also records with admiration the knowledge of astronomy among Mongol “diviners,” who are able to “predict the eclipses of the sun and moon.” And he describes in detail the elaborate process of making cosmos (fermented mare’s milk), which he then tries for the first time: “At the taste of it I broke out in a sweat with horror and surprise, for I had never drunk of it. It seemed to me, however, very palatable, as it really is.” During his journey back to Europe, he stops in the camp of the army chief Baiju in what is now Armenia. When his host serves him wine while drinking cosmos, Willem wishes he, too, were having mare’s milk. Willem’s interest in cosmos transcends the sphere of the anecdotal. To him, this concoction, which was at once food and drink, nutritious and flavorful, as well as easy to store and carry on long expeditions, bespeaks qualities such as ingenuity, austerity, and resilience that helped explain the military success of the Tartars. He concludes his report to Louis IX with the words: “I state it with confidence, that if your peasants…would but travel like the Tartar princes, and be content with like provisions, they would conquer the whole world.”

Odoric of Pordenone, another Franciscan friar, traveled through the East from the mid-1310s to the late 1320s. The friar died in Udine in 1330, leaving behind a precious account of his travels known as the Relatio. Odoric paints a portrait of India and its people that is morally complex, attentive to detail, and rich in its gray areas. He had made it as far as Cambalech (Beijing), where he remained for about three years as a guest of the Great Khan, Yesün Temür. In the opening section of his Relatio, he addresses the reader: “I, Friar Odoric of Friuli, can truly rehearse many great marvels which I did hear and see, when according to my wish I crossed the sea and visited the countries of the unbelievers in order to win some harvest of souls.” And marvels he does describe. In India, for example, Odoric sees black lions and bats as big as pigeons, witnesses celestial burials, and watches a nudist wedding. He visits an island in the middle of the Indian Ocean where men and women have faces like dogs, a city in China inhabited by pygmies, and many other marvelous things he chooses not to enumerate, “lest they should be deemed too hard for belief by such as have not seen them with their own eyes.” The lengthiest and most remarkable section of his Relatio deals with the recovery of the mortal remains of four Franciscan friars killed in Thânâh (Mumbai) in 1321. Here Odoric manages all at once to convey pity for his slain brothers, horror at the barbarity of their killers, and awe in the face of both the miracles of the Franciscans and the marvels of the Tartars.

According to Odoric, the friars had entered into a public dispute with the local qadi over theological matters. The argument escalated quickly, and at one point Friar Thomas of Tolentino proclaimed that the Prophet Muhammad was the son of the devil and lived in hell with his father. Not surprisingly, this provocation drove the qadi’s followers to demand the immediate execution of the Christians. Their first method was fire—but the Franciscans wouldn’t burn, which convinced many among the crowd that they were in fact saints. In describing the people’s reaction to the friars’ miraculous imperviousness to fire, the author appeals to the language of wonders: “Idolaters and others were standing about in a state of awe and astonishment, saying, ‘We have seen from these men things so great and marvelous that we know not what law we ought to follow and keep.’ ” The city’s religious and political leaders decided the Franciscans must still be put to death, in spite of the “great wonders” exhibited. The executioners were reluctant to carry out their orders and kill “good and holy men,” but they nevertheless complied and decapitated them. Right after the sentence was carried out, Odoric adds, “the air was illuminated and it became so bright that all were stricken with amazement…and after there were so great thundering, lightnings, and flashings of fire that almost all thought their end was come.”

If we were to make a distinction between miracle and marvel—both terms come from the Latin mirum, which means “admirable” or “astonishing,” and have been used interchangeably since antiquity—we would argue that whereas the miraculous is a supernatural occurrence explained only by the omnipotence of a specific divine will, the marvelous is a supernatural occurrence that falls outside any known cognitive paradigm or belief system. Although both the miracle and the marvel are spectacles, the cause of the former is ascribed to the divine, but the cause of the latter is yet to be determined. In short, the marvel is an enigma and the miracle a mystery. What is perceived as miraculous to a pious Christian like Odoric and his readers might have been experienced as a marvel by the inhabitants of Thânâh, who are either pagan or Muslim. And this is why the Muslims are not unanimous in their reactions; their attitudes shift between anger, convenience, awe, duty, and pity.

That massacre of missionary friars was by no means an isolated event. In Marrakech in 1220, a group of five Franciscans who were spreading the Gospel through North Africa were accused of committing blasphemies against Islam and executed. Seven friars, including Daniele Fasanella of Calabria, perished under similar circumstances in Ceuta in 1227. In 1266 two friars were flayed alive, their bodies then beaten and decapitated by Mamluks during the siege of the Templar fortress of Zefat, in Galilee. Half a century later, in 1314, three more met their demise in Erzincan, then part of the Ilkhanate under the Mongol Empire. Then came the 1321 massacre in Thânâh. By then the Franciscans had established dozens of missions all over central Asia. It was in Almaliq (now Xinjiang, in the northwest of China) where, in June 1339, six monks, a bishop, and a Genoese merchant were killed by order of the Khan Ali, a sultan who had only recently ascended to power after having had Yesun-Timur Khan, the city’s previous ruler, assassinated. One of the last such executions took place in Jerusalem in 1391, when four Franciscans were quartered alive and burned on charges of blasphemy. Other religious men who met similar deaths are Giovanni Martinozzi di Montepulciano, murdered in Cairo in 1345, and Girolamo di Firenze, killed in central Asia in 1362. All these bloody incidents are crucial to the history of Christianity because they bred a new generation of martyrs. A new iconography was born as well.

Throughout the fourteenth century, mendicant churches and monasteries all over Western Europe hired artists to decorate chapels, cenacles, and chapter rooms, to paint altarpieces, polyptychs, and other devotional artifacts, with scenes of Christian martyrdom. The objective was to commemorate the holy victims and, more important, to inspire churchgoers by providing visual evidence of the spiritual strength and unbreakable commitment displayed by these defenders of Christianity. Most examples of this iconographical trend are lost, but luckily a few have survived. The church of San Fermo Maggiore, in Verona, has a fresco of the martyrdom of Thânâh in which the Franciscan friars (five rather than four in this depiction) are shown hanged and cut in half. A reliquary painted by Taddeo Gaddi for the Basilica di Santa Croce, in Florence, includes an image of the martyrdom of the friars in Ceuta. In Padua, at the Basilica of Saint Anthony, one can see a fresco that depicts the same martyrdom, a Giottesque work dating from the first half of the trecento. No work, however, depicts the Tartars with as much detail and nuance as the Sienese fresco by Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

Sometime after 1730, The Martyrdom of the Franciscans was thoughtlessly whitewashed and was not rediscovered until the first half of the 1850s, when restoration work uncovered it beneath a thick layer of lime. In order to preserve it, it was removed and installed in the Bandini Piccolomini Chapel, inside the church, where it can still be seen today. There is no consensus among scholars on the issue of which historical martyrdom is depicted. Some have argued it had to be Thânâh. Others believe it could be a later event, perhaps one that took place in China in the 1330s, maybe the 1339 Almaliq massacre. Yet others claim that Lorenzetti’s fresco might not depict an actual historical event but could be a generic depiction of a scene of martyrdom in Asia.

The first feature of the scene that catches one’s attention is the fact that it unfolds on four neatly and carefully differentiated levels. On the bottom, we have the executions, followed by the witnesses, then the authorities, and finally the allegory of the vices. The contrast between the symmetrical disposition of the figures, forming a double pyramid, and the unspeakable brutality depicted in the scene has a shocking effect on the viewer. Isn’t evil supposed to be chaotic? Perhaps Lorenzetti, with the geography of Dante’s inferno in mind, is suggesting to the eye that evil, too, is hierarchical and, in its own way, harmonious, a grotesque imitation of the celestial order. It is a striking vision of violence.

The meticulous hierarchy resembles a dark inversion of a Maestà, an iconographic representation of the Virgin Mary enthroned with the baby Jesus. In a typical fourteenth-century Maestà, the forces of good descend from above until they reach the lowest part of the scene, which often featured the patrons. In Lorenzetti’s fresco all the good radiates from the martyred friars on the lower level, spreading up and out toward the viewer. The helplessness that the fourteenth-century viewer must have felt at seeing the friar about to be beheaded emphasizes the distance between spectator and scene, which takes place in remote lands. But it also reinforces the notion of a horror both unimaginable and beset with wonder. As the viewers are urged by the artist to be inspired by the martyrs’ ultimate sacrifice, they are also invited to stand in awe before the strangeness of the crowd.

In its physiognomic variety and taste for extravagant detail, Lorenzetti’s work parallels the travel narratives coming from the East at the time, like that of Odoric, and plays into the fascination with Asiatic marvels so common in fourteenth-century Europe. Whereas the spectators depicted at a Maestà tend to stare at the Madonna and her baby with expressions of unanimous enthrallment, the Saint Francis fresco offers a dizzying panorama the likes of which only the Pisano brothers and Giotto had accomplished before. It is possible that Lorenzetti may have looked for Asian models among the slaves and merchants in the great annual market in Pisa, a place where people from the most remote corners of the known world crossed paths. It is also worth noting that since the early days of the Pax Mongolica (a period that spanned roughly from the 1240s to the 1360s), Sienese merchants had been trading goods along the Silk Road, traveling as far as Tabriz, in today’s Iran. An artist working in Siena in the 1330s would, therefore, have had a vast and diverse picture of the world. One can imagine, too, that he would have had a pragmatic outlook on intercultural relations—and one certainly peppered with curiosity. Art historians have noted Lorenzetti’s realistic representation of the Tartars, possibly the first of its kind in the history of Western art. As an example of his attention to detail, historians point to the fact that the ornamental feathers of the helmet of one spectator are still attached to the bird’s foot—European painting would not see such naturalistic elements until well into the Renaissance. Some, like Roxann Prazniak, even argue that artists working in Tabriz, who painted landscapes for Mongol patrons, may have inspired Lorenzetti’s naturalism.

Most significant is the range of emotions and attitudes portrayed by Lorenzetti. Some of the Tartars appear to feel pity; others seem shocked. Some seem to empathize with the Franciscans regardless of their judgment of the fairness of the sentence. There are also those who do not look (are they sickened by it? Uninterested?); those who participate with glee (one even casts a stone at one of the cadavers); there are those who look with curiosity, with almost forensic interest; and those who look instead at the sultan or at one another, excited or appalled, maybe even in disbelief. The concession of humanity to the Tartars reveals itself as a wonder and reaffirms the conviction in the universality of the word of Christ that the artist and the Franciscan missioners shared. Nowhere is this emotional realism more evident than in the two figures who act as bookends to the picture and circumscribe the action: the executioners.

The one on the left holds the sword with one hand and prepares for a backhand stroke. His facial expression is one of concentrated rage. The one on the right has already completed his task and is sheathing the sword. The dark brown of his hair and beard, the metallic gray of the tunic, and the swarthiness of his skin would have evoked for the fourteenth-century Sienese spectator a world that was distant, mysterious, and wild. The executioner’s look is one of exhaustion and brutality. His eyes, indifferent yet somehow sad; his prominent belly; his muscular calves; his monstrous feet; his arms’ muscles still in tension; his expert hands—all come together to produce an image of shocking vivacity that inspires both terror and awe. His ragged tunic, his disheveled long hair, and his unkempt beard recall Saint John the Baptist—but a Baptist who decapitates instead of getting decapitated. As he puts away his sword, he doesn’t look at the sheath; his glance is directed nowhere. The automatic motion of the executioner’s hand reveals his expertise. The three cleanly severed heads at his feet (we can see only two today due to damage) confirm his competence as an executioner. Lorenzetti presents the Tartar butcher as much more than an icon of barbarism: he is, at once, a monstrous figure and a human being with complex emotions that Western viewers cannot know. Surrounded by what the artist’s audience would have seen as an exotic crowd in strange attire, immersed in a situation of foreign brutality, the mystery of the executioner’s sullen face is perhaps the greatest of all wonders in the painting.

Its effort to capture the humanity of a foreign foe makes the fresco a remarkable anomaly of the time. Lorenzetti’s skill and sensibility succeed in building bridges between the Christian West and the East by merging fear and wonder into a complex vision of common humanity. In this respect, his vision is reminiscent of Odoric’s: both offer a humanizing interplay of differing emotions among the Tartars, a group otherwise perceived as homogenously terrifying, the quintessential “other.” Recounting his sojourn in Cambalech, Odoric (who was, we shouldn’t forget, a mere ambassador, a glorified courier) says: “I, Friar Odoric, was full three years in that city and often present at those festivals of theirs; for we minor friars have a place assigned to us at the emperor’s court, and we be always in duty bound to go and give him our benison…In short, the court is truly magnificent, and the most perfectly ordered that there is in the world with barons, gentlemen, servants, secretaries, Christians, Turks, and idolaters, all receiving from the court what they have need of.” As he praises the order in the Great Khan’s court with unabashed admiration, and as he stresses the harmonious coexistence of its many and diverse elements, Odoric is implying that good government is not unique only to Christians. With order an essential attribute of the divine in the medieval Christian worldview, the implications of Odoric’s assumptions are at the least disquieting, calling into question the notion of Tartars as a satanic horde, and making for a political message that is both pragmatic and sensitive to otherness. That the authorities who received his message chose not to attend to its nuances should not surprise us. When it comes to geopolitical conflict, and in the interest of mobilizing the will of the people, the familiar logic of friends and enemies usually works better.

An epistolary exchange from 1245 between Pope Innocent IV and Güyük illustrates with frightening clarity the utter inability of East and West to understand each other. The message from the pope that Giovanni Da Pian del Carpini carried to the Great Khan began with a detailed summary of Christian dogma and ended with a series of requests (which read like commands) to treat the ambassadors with kindness and to refrain from further invasions of Western lands. Do otherwise, the pope suggests, and your people shall suffer the consequences of divine justice. The khan’s response, brought back by the friar and his entourage, is one of bewilderment. The khan first demands that the pope visit him in person if he wishes to make peace. He then adds, “The contents of your letter stated that we ought to be baptized and become Christians. To this we answer briefly that we do not understand in what way we ought to do this…You men of the West believe that you alone are Christians and despise others. But how can you know to whom God deigns to confer his grace? But we worshipping God have destroyed the whole earth from the east to the west in the power of God.” The letter ends with an ultimatum: the pope should either present himself in person and surrender to the khan or prepare for total war and certain defeat. Innocent IV did not accept the invitation. It would take another seven centuries and the invention of the airplane for a pope to visit the Far East, when Paul VI traveled to India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, and other Asian destinations between 1964 and 1970. By then, the Mongol Empire was long gone and the Vatican had lost most of its lands. Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s fresco, however, has survived, reminding the sporadic visitors to a poorly lit chapel in a Sienese church off the beaten path, that art often stands a better chance than politics and religion in finding elements that connect the most distant of cultures.