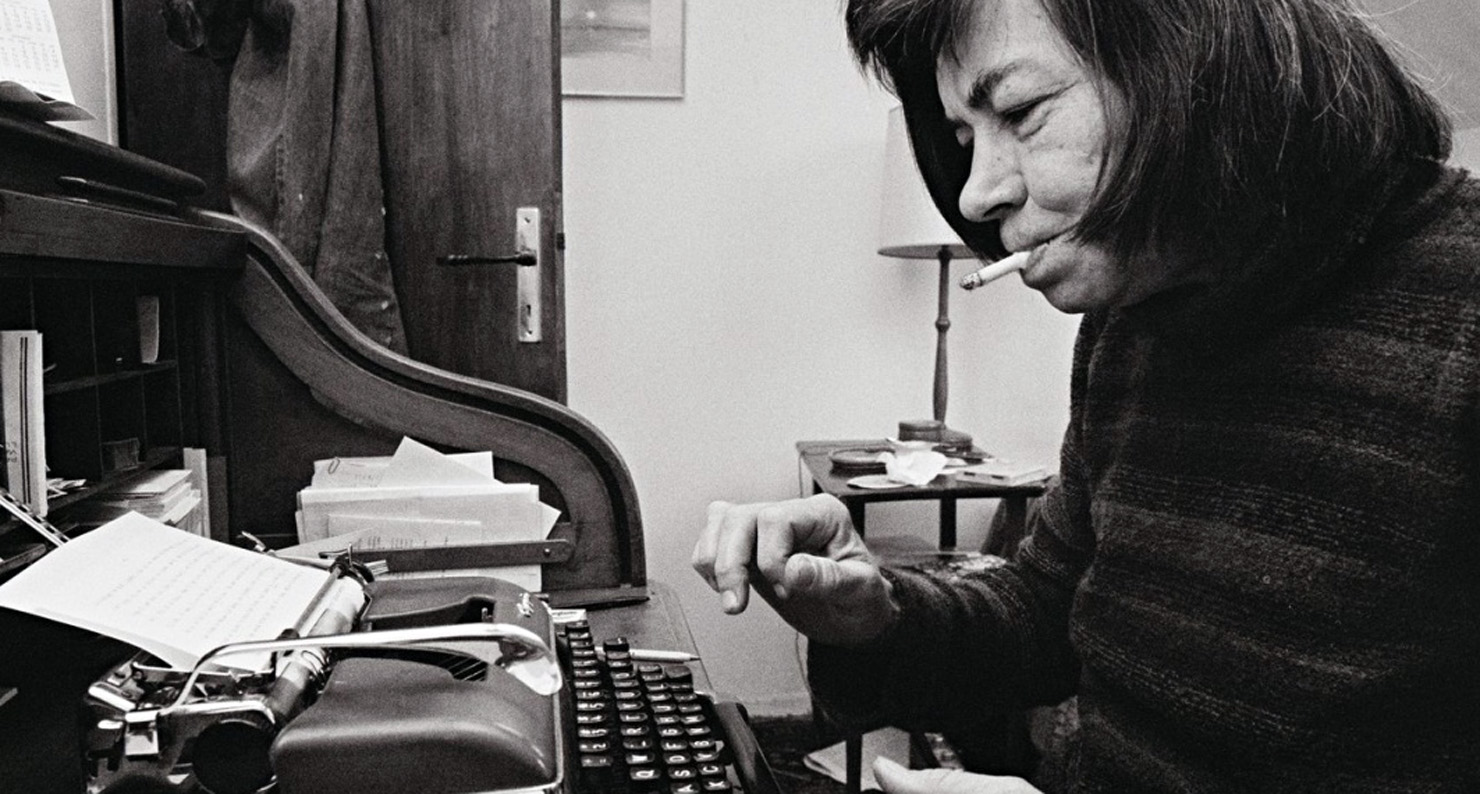

Patricia Highsmith at her typewriter in her home in France, 1976. As an expat, she was subject to both French and American tax systems. (Guardian)

Along with the long hours alone and the creeping madness, one of the questionable benefits of the writing life is that you are self-employed. This makes tax time an extra-special delight. Not only are the forms involved more complicated, but additional charges in the form of the self-employment tax are due. Writers not generally having a gift for finance, over the years they have gotten themselves in deep hot water with the Internal Revenue Service. Most famously, the critic Edmund Wilson decided not to pay his taxes from the years 1946 to 1955, then published a 120-page book justifying that decision in 1963. Sadly his book did not convince the IRS to mend what he saw as their avaricious ways; what amounted to an endless audit chased Wilson to his grave.

While doing some research on the novelist and critic Mary McCarthy—who as it happens was once married to Wilson but had divorced him by the time he decided to mount his anti-tax crusade—I was unsurprised to find that she too had had her issues with the tax man. Looking through her papers at Vassar, I was delighted to learn that she’d mostly articulated them to an unlikely person: the novelist Patricia Highsmith, best known for her Thomas Ripley novels and critically admired for the way she’d elevated the detective novel to a high art.

Most people don’t often connect Highsmith and McCarthy because they seem to be entirely different sorts of writers. McCarthy, famed in her time though less well-known now, wrote a lot of criticism and realistic literary novels, including The Group from 1963; Highsmith worked more with genre. But in the 1970s, both were spending a lot of time in Paris and met often. A lover of Highsmith’s told her biographer, Joan Schenkar, that Highsmith actually had a “great complex” about McCarthy. Highsmith was devastated during one of their meetings when McCarthy seemed never to have heard of Tom Ripley: “Is he a pop singer?” the critic asked.

Perhaps taxes were an easier subject between them because for McCarthy and Highsmith it was a shared interest. They were both expatriates, subject to both French and American tax regimes, and they both had income from multiple sources. In the late 1970s, Highsmith began to complain at length to McCarthy about upcoming American tax reforms, and about the huge accounting bills she was beginning to incur trying to stay atop the tide.

McCarthy sympathized, somewhat, though in typical McCarthy fashion she got in a mention of her superior bookkeeping skills. “We were audited a couple of years ago,” she wrote Highsmith, “and when it was over the IRS man told me I should have been an accountant, which quite astonished Jim [McCarthy’s husband].” Still, she too had a hard time with all the forms.

A 1978 letter to McCarthy is typical of the exchange. Highsmith was always clearly drowning under the weight of requirements; the question of geography presents itself as a solution, but not a good one. A new tax law won’t allow her to claim an exemption and France will now require a report of her world income. “Then the lying sets in, but how much lying? Uncomfortable. I think my accountant will propose I live six months elsewhere come next year.” In another letter to McCarthy, noting a friend’s move, Highsmith wrote, “Much as I like Santa Fe, I think one is putting one foot in the grave by buying a house and living there. And social life is something like an ingrown toenail.”

Of course none of the machinations Highsmith details in this or subsequent letters truly rescued her from taxes, either. As her biographer notes, Highsmith’s estate ended up paying substantial estate taxes—because by the time of her death, on some long ago accounting advice, Highsmith had left France and domiciled herself in Switzerland.