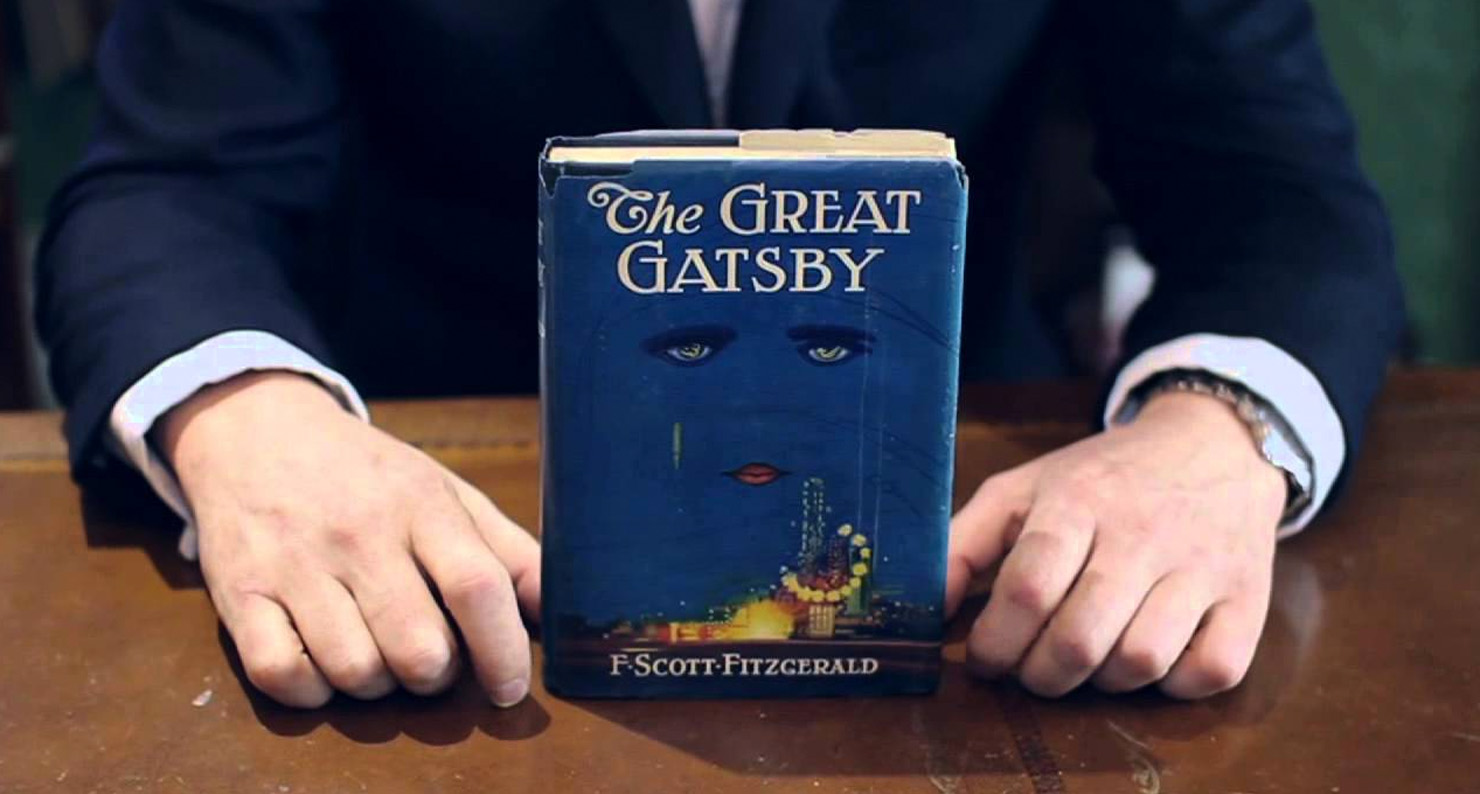

A first edition of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. (Peter Harrington)

This week marks the ninetieth anniversary of The Great Gatsby, first published on April 10, 1925. Gatsby enjoys such an iconic status among American novels that it’s easy to forget what a disappointing seller the book was for F. Scott Fitzgerald. His 1920 debut, This Side of Paradise, had been a surprise bestseller, and his next, The Beautiful and the Damned, was a hit as well: each sold about 50,000 copies. Fitzgerald privately considered The Great Gatsby “about the best American novel ever written,” and hoped to sell 75,000 copies. His editor at Scribner, Maxwell Perkins, considered the book “extraordinary.” “You have plainly mastered the craft,” he wrote, “but you needed far more than craftsmanship for this.” The early response from fellow writers—including Edith Wharton, Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein—was enthusiastic. T.S. Eliot reported that he had read The Great Gatsby three times and thought it was “the first step forward American fiction had taken since Henry James.”

Reviews, however, were dismissive. One of the first notices, in the New York World, declares “F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Latest a Dud.” The evening edition of the paper concluded its review: “We are quite convinced after reading The Great Gatsby that Mr. Fitzgerald is not one of the great American writers of today.” The reviewer at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle took fault with the jacket copy:

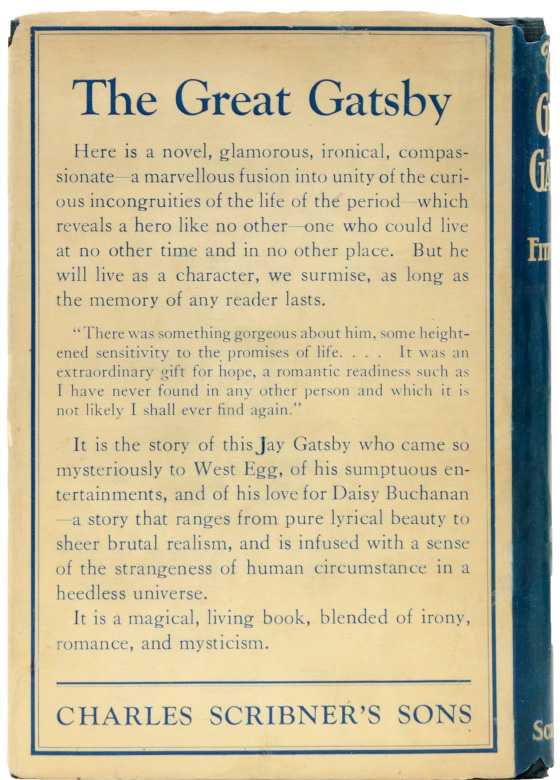

Now I have just read The Great Gatsby, published by Scribner’s, with a note on the book jacket to the effect that “it is a magical, living book, blended of irony, romance and mysticism.” Well of course, I suppose the Scribner jacket writer wants to well as many books as he can, otherwise I swear I would think he had gone completely mad. Find me one chemical trace of magic, life, irony, romance or mysticism in all The Great Gatsby and I will bind myself to read one Scott Fitzgerald book a week for the rest of my life. The boy is simply puttering around.

A few positive reviews remained (“New Fitzgerald Book Proves He’s Really a Writer,” The Chicago Daily Tribune), but Gatsby sank out of sight. The first printing of 20,870 copies eventually sold, and Scribner printed only 3,000 more. When Fitzgerald died fifteen years later, there were still copies of that second printing on warehouse shelves. In 1934 Gatsby was briefly revived by the Modern Library, but was discontinued when it failed to sell 5,000 copies in five years. It wasn’t until World War II, when the Council on Books in Wartime distributed 155,000 paperback copies of The Great Gatsby to American troops, that the novel found its audience, emerging as a perennial contender for the title of Great American Novel, and launching thousands of high school essays on the symbolism of the green light. Today, ninety years after its first appearance, The Great Gatsby is a backlist star, selling a half-million copies every year.

In the rare book trade, where I make my business, Fitzgerald’s glorious failure is one of the most sought-after modern first editions: a book that people love to see and hold and discuss, even if they have no intention of buying it. Like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Catcher in the Rye, The Great Gatsby is a novel widely assigned to Americans at an impressionable age, so that even people who might not consider themselves readers have read The Great Gatsby, or feel that they have. It’s a favorite “favorite book,” and a sentimental object of desire: the unusual first edition that appeals beyond the circle of serious book collectors to a larger community of readers. There are copies of Gatsby available all the time—like Huck and Catcher, the first edition is always obtainable, if you have the money. (A copy is currently available with an unrestored dust jacket for $150,000.) For rare book dealers, talking about the value of The Great Gatsby is an easy way to introduce new collectors to the logic of the book trade, because what’s true of modern firsts in general is wildly, extravagantly true of Gatsby. The first edition of The Great Gatsby isn’t a particularly scarce book. A first printing of twenty thousand means there will typically be multiple copies for sale. (Sylvia Beach published just one thousand copies of James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922, and Scribner would publish five thousand copies of Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises in 1926.) Collectors draw distinctions among the first twenty thousand copies of Gatsby, narrowing the field a bit. There were five typos in the original setting of Fitzgerald’s text, gradually corrected over the course of the first printing, so the most desirable Gatsby will be a first printing, first issue, with all five mistakes present. (For those playing along at home: in the first issue, on page 205, Meyer Wolfsheim’s secretary tells Nick Carraway she’s “sick in tired” of young men trying to force their way into the office.) Even so, uncorrected first-issue copies come up all the time, with dealers and at auction and on eBay, perhaps at a church jumble sale near you. Budget $5,000 for a “fine” quality first printing, first issue Gatsby, without the dust jacket.

A first edition, first printing, complete with five typos, wrapped in the original jacket, is a different story. The market history of The Great Gatsby underscores the importance—what many would call the arbitrarily freakish value—of the original dust jacket on a modern first edition. Any first edition “in jacket” is worth more than an unjacketed copy, but a first edition of Gatsby in the original jacket, with those eyes and lips suspended in a deep blue sky, is worth exponentially more, a quick leap from four figures to six. In April 2014, at the Sotheby’s sale of Gordon Waldorf’s library, a near-fine copy of The Great Gatsby in an unrestored jacket set a world record, fetching $377,000 with the buyer’s premium. In his authoritative history of the book jacket, collector and bibliographer G. Thomas Tanselle calls Gatsby “the inevitable example” of what a jacket can mean for a modern first edition’s value, “the classic holy grail.” That jacket, as antiquarian book dealer Adam Douglas observes, is “the most expensive single piece of paper in twentieth century book collecting.”

Gatsby’s jacket is prized, in part, because it’s so fragile. Most books lose their jackets over time, as the paper tears or fades, and owners toss them away. Gatsby’s jacket was printed on brittle stock, sized slightly too tall for the book, so that the top edge chipped almost immediately. It’s a tricky jacket to maintain in fine condition, and most readers didn’t bother, discarding the ill-fitting sleeve and preferring Gatsby’s dark green cloth binding, which matched those of Fitzgerald’s earlier books from Scribner. Surviving examples of the original jacket are usually damaged, patched, or painted, which is why the Waldorf copy was exceptional, truly bright and unrestored. The first issue jacket, like the first issue book, also contains a typo that establishes priority: on the back panel, there’s a lowercase “j” in “Jay Gatsby,” which had to be corrected in ink on all the first issue jackets. (The Waldorf copy had the telling misprint as well.)

The appeal of Gatsby’s jacket goes beyond mere scarcity, however, to the impact the jacket had on Fitzgerald himself. Most cover designs, then and now, were decorative afterthoughts, commissioned by the publisher after a book was finished. The jackets of Fitzgerald’s earlier novels feature flappers that pointedly resemble his wife, Zelda, drawn by W.E. Hill in a brisk commercial style familiar to readers of the New York Tribune. Francis Cugat’s dramatic full-color design for Gatsby is something else: a woman’s glowing features float in the night sky over the carnival lights of Coney Island, while a bright vertical streak suggests the trail of a firework or a tear. When Fitzgerald was at work on Gatsby, Maxwell Perkins showed him Cugat’s idea: perhaps a preliminary sketch, perhaps the final painting. Fitzgerald’s response, sent from the French Riviera, is legendary: “For Christ’s sake, don’t give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me. I’ve written it into the book.” In Nick’s description of Daisy Buchanan as the “girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs,” and in the blank eyes of the oculist T.J. Eckleburg’s roadside billboard, Fitzgerald picked up and transformed elements of Cugat’s design, in a singular collaboration between artist and writer. (Francis Cugat would be a one-hit wonder of modern American book design: after his essential contribution to the completion of The Great Gatsby, he left to work in Hollywood and never designed another jacket.)

Not everyone was a fan of The Great Gatsby’s cover art. Hemingway famously complained in A Moveable Feast that it looked like “the book jacket for a book of bad science fiction.” From the 1930s through the 1970s, Gatsby was reissued with a series of different cover designs, including Alvin Lustig’s crisp take on the dollar bill for New Directions. But Cugat’s original design, like the novel it influenced, gained admirers as the years passed. Revived and reproduced on T-shirts, tote bags, and posters, that glittering nighttime scene defines Gatsby for contemporary readers. When Scribner briefly offered a photographic cover featuring the stars and starlets of Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 3D film adaptation, readers rebelled: “We never even took the nonmovie tie-in edition out of print,” Scribner editor-in-chief Nan Graham said. “And still we got into trouble.” And so that first-edition jacket, timeless and virtually priceless, turns obsessed collectors into Gatsby—except unlike the trifling Daisy, the book justifies the tribute.