First of all, you will have to deal with a desert mafia. For if they are not your guides and your guards, they will rob you. In the past, the severed heads of these Berber bandits covered the ground of the palace at Sijilmasa; there were highwaymen, then, who stopped you across the Sahara en route to the Land of the Blacks. It was the end of the thirteenth century. Authority in North Africa belonged to the Almohads. Though very much concerned with moral and legal precepts, they were not much concerned with protecting their neighbors’ lives. In other periods, robbers were converted into protectors—for a price, of course. Between mid-February and mid-April 1352, Ibn Battuta, the Moroccan traveler who delighted in exploring the whole of the Islamic world, crossed the Sahara. The Masufa, a tribe of the Sanhaja confederation, controlled the caravan. Let’s be clear: the leader of the caravan, the scouts, the camel drivers, the guards were all from this tribe. It was better to put one’s fate into their hands than to fall into their hands. Anyway, one was forced to trust them: the guide of Ibn Battuta’s caravan was blind in one eye, or at least that’s what the caravan members were led to believe, but he remained the authority on a route that was not easily visible, as a Roman commercial road would be, a route that wound through loose, stony ground and was always susceptible, as they were also led to believe, to being hidden beneath “mountains of sand.”

Then there was the problem of water. It would be even better to say the problem of thirst, your constant companion during the crossing. All travelers, all geographers say the same thing: the water is sometimes “fetid and lethal” and, Yaqut al-Hamawi humorously reckons, “has none of the qualities of water other than being liquid.” Such a beverage inevitably generates intestinal pains that make life difficult and sour the memory of the trans-Saharan experience. In good years, when there had been plenty of rain, water filled the rocky gullies, and people could drink and do laundry. In bad years, the burning wind dried out the water in the goatskins; consequently, a camel’s throat had to be cut and its stomach removed. The water it contained was drawn off into a sump and drunk with a straw. In the worst-case scenario, one could kill an addax antelope and follow a similar procedure to extract greenish water from its entrails. Some authors remembered that the Maqqarî had formerly “established the desert route by digging wells and seeing to the security of merchants.” But it was during the period when the big merchants of North Africa purported to deal with the material organization of the caravan and the route themselves; it was a time when captured bandits had their heads cut off. At that time, the caravan’s departure was announced by the beating of a drum, while a standard, probably that of the ruler of Sijilmasa, fluttered in the wind in front of the caravan. Since then, the merchants resigned themselves to outsourcing the organization of the crossing to the desert nomads, and, whether the maintenance lapsed under the reformed bandits or whether the new caravan masters thought it right to justify their services’ high prices, the wells disappeared. Thirst would kill you, but death is less painful than what brings it about: first you experience a sort of sluggishness before losing consciousness; had you been lost alone, you would either be found or not. “It’s the leading cause of death in the Sahara,” a twentieth-century French colonial officers’ manual warned its readers.

A shopkeeper’s mind-set was needed in the caravan. You would buy your camels at Sijilmasa, then let them fatten for four months, as Ibn Battuta did, so that they could handle the crossing. Some big merchants had hundreds of the beasts, others only a few. One could never depart with only one camel; at least two were needed: one for you, one for the baggage. If you rode a horse, you had to bring water for it to drink. Before departure, each merchant made arrangements for his merchandise as well as for his saddlery and supplies. At the last moment, the members of the caravan filled their guerba, water containers made of goatskins. It was also necessary to get recommendations about where to stay when one reached one’s destination—someone needed to book a house or room. En route, everything has its price; nothing is held in common. The nomads provided only their knowledge of the route and the security of the column. At the hottest time of the day, all pitch their tents. The travelers needed to be able to count on their servants for the menial tasks. The guards had to be bribed to watch your goods or to refrain from stealing them themselves. On the return trip, you’d be well advised to keep an eye on your gold and slaves. But even if you kept a watchful eye, this business still came with troubles. The following anecdote, which dates from the early thirteenth century, has the value of a parable: “My maternal uncle,” a merchant says, “undertook a voyage to the south to trade gold. He bought a camel to get there. While traveling, he found himself in the company of a city-dweller…The city-dweller had started his slave business. Both of them took the caravan back home. My uncle felt comfortable and free from worry: if the caravan left, he mounted his camel; if the caravan halted, he pitched his tent and rested. But our city-dweller was exhausted and overwhelmed with worries about his slaves: one was wasting away, another was hungry, this one escaped, that one got lost in the erg [duned desert]. When the caravan stopped, each attended to his own affairs. Our city-dweller was entirely worn out. During this time, he looked at [my uncle], who was seated peacefully in the shade with his fortune.” How many stories circulated about old seasoned travelers taking advantage of city-dwellers as ambitious as they were inexperienced?

And then there were the small, but numerous and in the end obnoxious, daily inconveniences: the omnipresent fleas, which you would try to drive away by wearing cords soaked in mercury around your neck; the numerous flies everywhere there was a rotting carcass (i.e., precisely around the wells and the camps); the snakes. In the caravan of February 1352—Ibn Battuta’s caravan—a certain al-Hajj Zayyan, a merchant of Tlemcen in present-day Algeria who loved to catch snakes and play with them, was bitten on his index finger. The injury was cauterized with a red-hot iron; then, as a remedy, he cut the throat of a camel and put his hand into the animal’s stomach and left it there the whole night. Was it really useful? He thought so. In any case, it wasn’t enough: he had to cut it off at the joint. The Masufa must have laughed a lot at these city-dweller pastimes. Either pretending to be experts or eager to paint a bleak picture of the risks, they said that the bite would have been fatal if the serpent hadn’t drunk water before biting him. Finally, there are the demons, which Ibn Battuta says are numerous in the desert. These imperceptible deities like to toy with isolated travelers. Mischievous, they seduce you so that you end up losing your way.

The caravan tempers these harsh conditions with strict discipline; it diminishes them through distractions. You will put distance between yourself and the column only at your own risk, the Berber leader must have said. The camels, indeed, walk as if to the beat of a metronome. They will stop when they receive the order to do so, that is to say, at the planned halt on a beeline route. And while the camels carrying the loads were underway at a regular pace, under the guidance of the impassive Masufa, those who paid for the crossing would amuse themselves hunting addax, letting their dogs run free, and riding a bit ahead of the caravan to let their horses graze and to enjoy the invigorating wait. But the games, the intemperance of the city-dwellers, could cost them dearly. Even though caravans could be made up of hundreds, sometimes even thousands, of camels, one could quickly lose sight of them behind a curtain of dunes. Two cousins, Ibn Ziri and Ibn Adi, were members of our Moroccan traveler’s caravan. The two argued, and Ibn Ziri let himself pull back from the rest of the caravan to show his annoyance. That was the first mistake! “When the people encamped there was no news of him,” writes Ibn Battuta. “I advised his cousin to hire one of the Masufa to follow his track in the hope of finding him, but he refused.” Second mistake! “Next day one of the Masufa undertook, without pay, to look for him. He found his trace, which sometimes followed the beaten track and sometimes left it, but could get no news of him.” Should he have sent this guard unpaid? This was perhaps the third mistake. We will never know which one of these mistakes was fatal. A few centuries later, on the same stretch of desert, but from the opposite direction, a caravan of pilgrims lost two of its members in a row and yet noticed only a day and a night after they disappeared. The author of the story concludes philosophically: “But our conscience was clear because we had warned them of the risks they were running by not abiding by the rules of the caravan.”

After a two-month journey, you will arrive at the end of the crossing. In the fourteenth century, the point of arrival was Oualata, in what is now southeast Mauritania. You are already in another world. A few days earlier, a messenger hurried ahead to announce the caravan’s arrival. He carried letters from the travelers to the city’s merchants. At the news, the people of Oualata sent loads of water, which of course were sold to the travelers, but which would help the men and horses to cross the final segment of the route, through a sweltering, sterile desert—so sweltering, in fact, that the caravan could travel only at night.

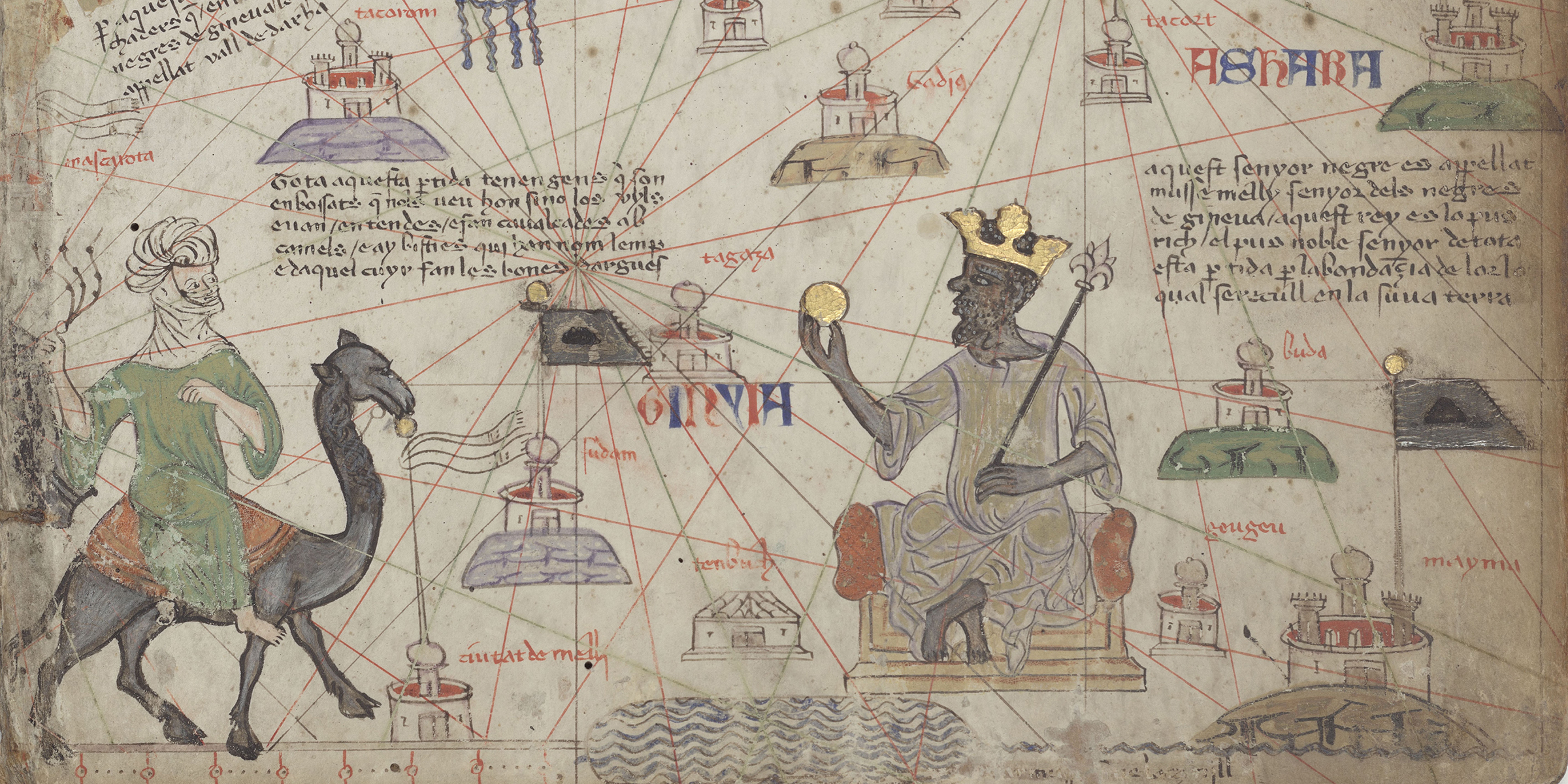

Ibn Battuta arrived in Oualata at the beginning of the first month of Rabi in the year 753 of the Muslim calendar (i.e., in the days following April 17, 1352). The heat there was torrid. “There are,” he writes, “a few little palm trees there in the shade of which they sow water melons. Their water comes from ahsa’ [water holes] there. Mutton is abundant there and the people’s clothes are of Egyptian cloth, of good quality…[The] women are of surpassing beauty and have a higher status than the men.” These are the impressions of a tourist, a bit short on detail for someone who stayed in the city for fifty days. The population was Masufa Berber. North African merchants had established a residence there; it was through a man from Salé, another Moroccan, that our traveler found a house to rent. But the order that reigned there emanated from Mali, the powerful black kingdom that had already made Oualata one of its possessions, the “first district of the Sudan,” at a distance of twenty-four days from the capital to the south. You see the governor of the city, the farba, a Manding title. “He was sitting on a carpet…with his assistants in front of him with lances and bows in their hands and the chief men of the Masufa behind him. The merchants stood before him while he addressed them, in spite of their proximity to him, through an interpreter, out of contempt for them.” The arrangement was as precise as the rules of the protocol: the armed guards stood before the governor, the local dignitaries behind him.

The camels had barely set foot in the city, Ibn Battuta tells us, when “the merchants placed their belongings in an open space, where the Sudan took over the guard of them” while the merchants went to pay tribute to the governor. This haste and the marks of respect that the merchants made to the farba shocked our author: “At this I repented at having come to their country because of their ill manners and their contempt for white men.” Invited later by the mushrif, an Arabic term for tax collector, to a light meal to welcome the caravan, he stiffened again; it was as if he barely glanced at the dish of crushed millet mixed with honey and yogurt served to the guests in a gourd. “Was it to this that the black man invited us?” he asked his companions with, one guesses, an affected frown. “They said: ‘Yes, for them this is a great banquet.’ ”

Such haughtiness prevented Ibn Battuta from seeing what was at stake around him. The rules of etiquette, the discipline, the assaults of politeness to which each yielded with diligence are testament to a world of subtler codes than the severity of the caravan drivers. The merchants, who had dearly longed for the moment they could at last escape from the control of the caravanners, entered this new world right away, but not the tourist, who traveled bringing his own world with him. At Oualata, the merchant entered Mali. It was a frontier post, then a customs post. If the merchants immediately unloaded the camels on the open space and left everything under guard, it was because this was necessary for calculating the appropriate tax to be paid based on the weight of the merchandise. When the scouts were sent ahead of the caravan, it was perhaps also to avoid venturing onto a smuggler’s route. You have left the mafia; you have entered the state.

Excerpted from The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages by François-Xavier Fauvelle, translated by Troy Tice, and illustrated by Roland Sárkány. Originally titled Le rhinocéros d’or. Original French edition © Alma éditeur, Paris, 2013. Copyright © 2018 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.