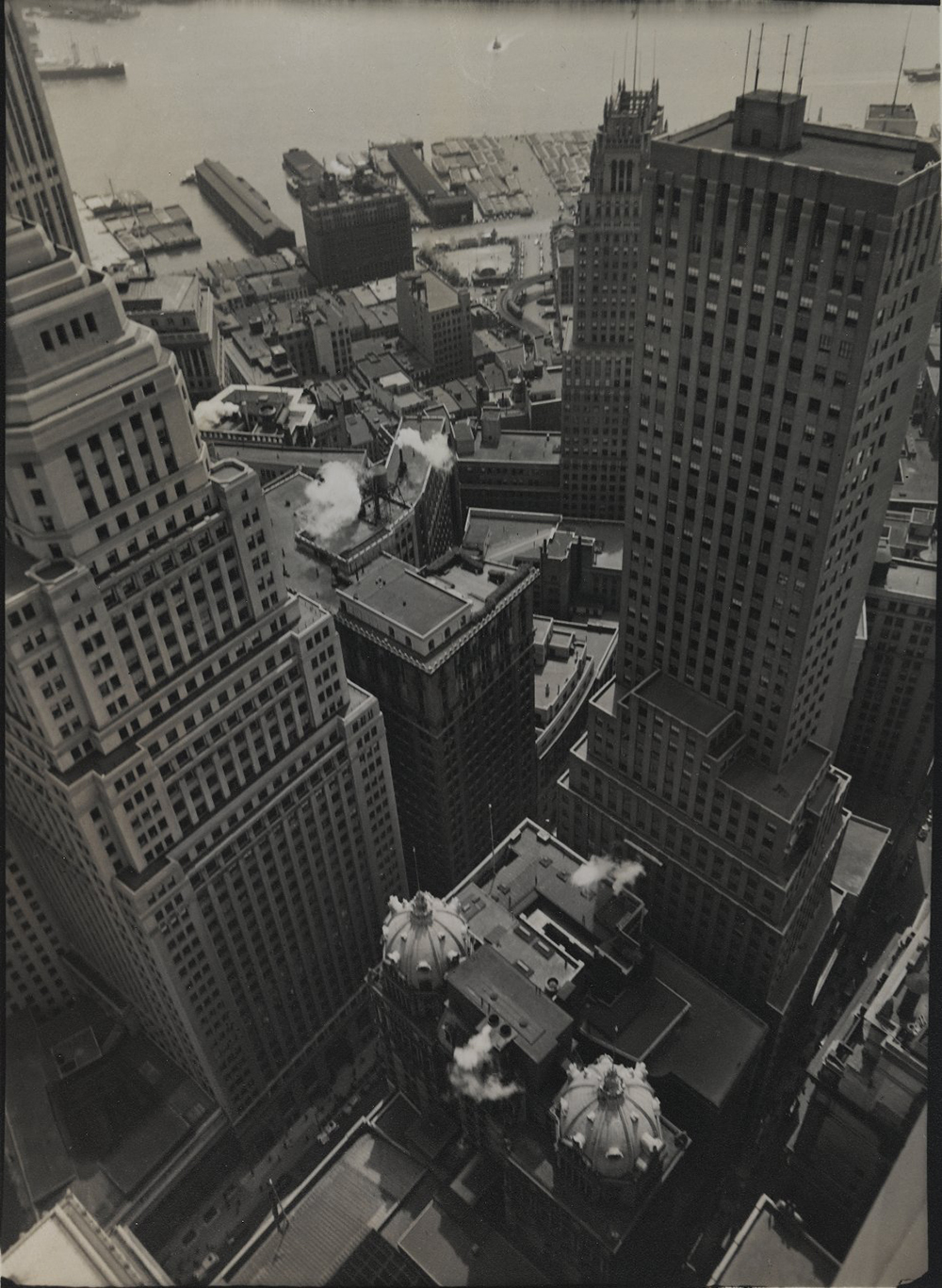

New York City views, skyline, c. 1931. Photograph by Arnold Genthe. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1921 painter and photographer Charles Sheeler and photographer Paul Strand made what is often considered the first American avant-garde film, Manhatta. The film cycles through a typical day in industrial New York City. The camera lingers at eye level, documenting commuters hurrying off the ferry and the bottleneck crowds before its gaze rises upward, hovering a story or two off the ground to capture the stomachs of skyscrapers. Manhattan’s skyline, featured prominently throughout the fast-paced ten-minute documentary, is periodically interrupted by quotes from Walt Whitman’s 1855 poem “Leaves of Grass,” which fill the screen with text, similar to that of silent films, as the nocturnal city skyline flickers in the background.

City of tall facades

of marble and iron,

Proud and passionate city.

The architecture of the city becomes the film’s protagonist.

The New York skyline is ripe for the role; its architecture is distinctly recognizable. The shiny facades work as a metaphor either for success or the darker undertones of the city’s criminal activity: the romantic comedy or the noir. The cinematic city of New York exists in extremes: aspirational or undesirable. In this way, the city becomes elusive, static in time and meaning, opposed to the real, ever-shifting city and the feelings you have toward it, whether you glance at it from the turn of the twentieth or the twenty-first century.

For example, watch the camera tantalizingly slide down the reflective skyscrapers until it reaches street level in Maid in Manhattan (2002). A flustered Jennifer Lopez, clad in shades of camel, rushes against the tide of men donned in black suits. Her quick gait is in direct opposition to the patient shots of the buildings that are used to introduce each scene. Even if the skyline weren’t included so prominently throughout the film, the viewer still knows that the city is important because of its presence in the title. This rags-to-riches story starts out by showing the city as genuine. The opening montage switches from aerial shots of the Statue of Liberty and the Empire State Building to eye-level scenes from the Bronx—street vendors selling fruit, a man sweeping an alley, shoes thrown over an electrical wire—before it defaults to more clinical shots of Manhattan streets and Central Park as a way to metaphorically show the protagonist’s rise into the world of the upper class. At the end, when the U.S. Senate candidate chooses Lopez in spite of her status as a maid, they kiss in front of a mural of the New York City skyline as tabloid photographers clamor to get a shot. The emphasis on the New York setting hints that the plot couldn’t be happening anywhere but New York.

Sheeler and Strand’s canonical piece of cinema is a predecessor to the now-prevalent B-roll footage—the supplementary images in films—of architecture that is used to establish settings in television shows or movies (including Jennifer Lopez vehicles), where it takes on a supporting role. Spliced between shots moving the plot forward, B-roll works to support the narrative in a variety of ways: to connote the end of a scene or a shift in location, to add some visual stimulation and variety, and, in the case of B-roll of architecture, to say something important about the city where the film takes place.

Skyscrapers dominate the footage they occupy—one reason for New York’s role as a distinct movie city, despite its distance from the epicenter of filmmaking. As Eve Babitz wrote about Los Angeles, “It’s difficult to be truly serious when you’re in a city that can’t even put up a skyscraper for fear the earth will start up one day and bring the whole thing down.” In the docu-essay Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), panning shots of the L.A. skyline from the films Hickey & Boggs (1972), Out of Bounds (1986), and They Live (1988) alternate on-screen, as director Thom Andersen observes the tension between urban sprawl and the audience’s need for a place to look:

Movies are vertical, at least when they’re projected on-screen. The city is horizontal, except for what we call downtown. Maybe that’s why the movies love downtown more than we do. If it isn’t the site of the action, they try to stick its high-rise towers in the back of the shots.

Snapshots of a “city of tall facades” create an overarching sense of place in an instant.

To better understand the transition from Manhatta to more clichéd shots of the city, such as those found in Sex and the City, we can look to the work of Auguste and Louis Lumière, whose footage of the city preceded Strand and Sheeler’s version. In 1896 the Lumière Brothers traveled to America to take their new invention, the cinématographe, on tour. A cumbersome predecessor to both the modern video camera and the projector, the cinématographe housed a camera inside a box that was then hoisted upright by a tripod and cranked by hand to capture footage. While in New York, the brothers filmed eleven short plotless films of the skyline and the everyday lives of New Yorkers. One short film—less than a minute long—lingers on Broadway. Streetcars and horse-drawn carriages come and go into the vanishing line; men wander past leisurely, sometimes curiously looking into the camera’s lens, interested in the novel invention. These films inspired the city symphony, a genre of film that gained prominence in the 1920s and includes Manhatta. City symphonies are documentary-style films that compile shots of a city. They were made all over the world: Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien Que Les Heures (1926) in Paris, Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) in the Soviet Union, G.W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street (1925) in Vienna, and Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) in Berlin.

Montages of cities became a feature of mainstream cinema shortly after the art house aesthetic of the city symphony took off. The city flashed before the eyes of the viewer of film noir and gangster films to quickly introduce the “seedy” metropolis where the film would take place. In his essay “Chinese Boxes and Russian Dolls: Tracking the Elusive Cinematic City,” Colin McArthur cites G-Man (1936) as a good example of how the city montage,

usually made up of speeding automobiles, blasting machine guns, and newspaper headlines, offers a condensation of the idea of “cityness.” Indeed, a freeze-frame from such a sequence, taken from the heart of a piece of Mass Art, would not be dissimilar to certain High Art photomontages of the same period.

City symphonies still crop up from time to time. Chantal Akerman cycles through shots of New York at street level while a voice-over reads aloud letters from her mother in her 1976 film News from Home. Akerman’s footage of New York is peculiarly underpopulated, shot very early in the morning when few cars or people were on the streets. And yet the skyscrapers and tall buildings hint at the dense population of the city. Today the meandering shots of cities around the world that are used as Apple TV screensavers could be classified as a new kind of city symphony. The aerial views of the city zoom in achingly slowly, shot by drone and helicopters, and make it seem as if the cities are uninhabited—the opposite intention of the original city symphonies.

Prominent versions of the city symphony can be found in the opening credits of films and television shows. The opening credits of Working Girl (1988) are a shot-by-shot facsimile of Manhatta: swooping shot of the city, the ferry, the commuters filing off the ferry in a bottleneck, a shot of people walking along a busy street in Manhattan. These establishing shots introduce the viewer to the narrative by way of the setting and ensure that it will play a meaningful role in the story. In The Devil Wears Prada (2006), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), Younger (2018), and She’s Gotta Have It (both the 1986 film and the 2017 TV show), the skyline of New York is the first thing the viewer sees.

The version of New York City used on-screen can be split into two major categories: the dark underbelly of the city found in noirs, gangster films, and TV procedurals, and the shiny optimism found in rom-coms and comedies. A tale of two cities, so to speak. Both have separate aesthetics that quickly signal to viewers what kind of film they’re watching. NYC noirs show a dark and lecherous montage of the city, portraying the city as unwelcome, such as the Law & Order opening. Montages in rom-coms show the city during the day: bright and sunny, bustling. If there is a night shot, it’s most likely of the sanitized version of twentieth-century Times Square. New York as a land of opportunity, whether it be for a career or a love interest, is the image projected.

A third category of film might be considered a mix: a successful businessperson is secretly involved in criminal activity. In these films, the shots of the city cycle between unruly and disheveled and bright and shiny. The former is typically shown at night, while the latter are daytime scenes, mirroring the dual nature of both the city and the main character. No film does this better than American Psycho (2000), directed by Mary Harron. The facades of the Manhattan skyscrapers reflect the sun during the day, when Patrick Bateman is a successful businessman. But at night, Bateman goes on his killing sprees.

These dichotomies can be directly traced to the anxieties or optimism of the year they were filmed. Neither films nor architecture can ever be completely divorced from the politics of their settings: buildings and narratives echo the political climate of the moment, such as the ping-pong between fear of crime and lust for wealth of the 1980s or the not-long-for-this-world economic sunniness of the 1990s. The semiotic potency of skyscrapers became clear when films shifted in reaction to 9/11. Prior to September 11, 2001, the Twin Towers were displayed prominently in films and television, the distinct matchstick buildings standing out above the skyline. After the attacks, the symbolism of the buildings shifted from “New York” and “success” to that of extreme tragedy and loss. Films that were slated for release in the months following the attack—Zoolander, Serendipity, Spider-Man—scrubbed the towers from their footage, circumventing any potential reminders of the tragedy that might counter the entertainment value of the films. While films like Spike Lee’s 25th Hour (2002) and the fourth season of The Sopranos leave the Towers absent in the opening city montages, the serious nature of the narratives allow the characters to address the attacks, however vaguely.

Sometimes the inclusion of architecture shot has less to do with metaphor and more to do with logistics, such as when a story is set in New York City but filmed elsewhere. Suits, which was filmed in Toronto, is a good example, as are a plethora of cop shows. American Psycho was shot partly in Toronto—the building where Patrick works is the TD Centre, but the architect Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe built an almost identical building in Manhattan: the Seagram Building. These films and television shows use stock footage of the New York streets to demonstrate where the story is taking place while saving money by filming elsewhere. By interjecting montages of the city, made up of shots that could double as postcards, these films and television shows employ the techniques of city symphonies—which often filmed real people—to forge its false location.

The sprawling montages in film and television can be thought of as a cine-flaneur. The images themselves are a cinematic version of the flaneur, and in turn allow the viewer to become a flaneur of the city in question. A flaneur wanders the city with an open mind, receptive to getting lost. Flaneurs don’t enter but instead observe the architecture that makes up the city. In Los Angeles Plays Itself, Andersen narrates the difference between us and the potential of the cine-flaneur. “But movies have some advantages over us: they can fly through the air, we must travel by land. They exist in space. We live in dying time,” he says. The montage of the skyscrapers and skyline gives the viewer a new way to consider the city. “Like the urban spectacle of flânerie, the mobile gaze of the cinema transformed the city into cityscape, re-creating motion of a journey for the spectator,” writes Giuliana Bruno in her essay “City Views; The Voyage of Film Images.”

Stock images and B-roll have rendered the spectacle of the cine-flaneur void. In its place is a predictable image of the city, one that works harder to be recognizable than to introduce. Perhaps nothing embodies the decline of a true city symphony like Woody Allen on his film Manhattan (1979): “I presented a view of the city as I’d like it to be and as it can be today, if you take the trouble to walk on the right streets.” This is the opposite of Sheeler and Strand’s Manhatta, which shows that there are no right streets to walk down. Allen’s New York is that of the upper strata; the right streets to walk down are safe and upscale, the shabby streets are unworthy of his purported flaneur. In truer flaneur style, Manhatta loves every street of the city equally. But a supporting character, like that played by the contemporary version of New York on-screen, doesn’t have to be as deep and complicated as the main character. Instead, the city gets typecast in the dichotomous role of either good guy or bad guy. The architecture of the city supports the narrative of the film.

This one-dimensional casting of the city has replicated itself on social media. The short bursts of video one is able to upload to Instagram replicates the city symphony in structure only. The content veers toward capturing the landmarks of the city, skirting the authentic experience of the city’s architecture. Social media heightens the inauthenticity of the city; plotless Instagram videos and posts of New York skyscrapers are akin to the contemporary version of a stamp on a passport or an I <3 NY T-shirt. Their only effect is to project that you have been to a place. Bruno calls New York (and also Naples) cine-cities that mirror the experience of being both a tourist attraction and a nightmare; their “very history is intertwined with tourism, colonization, and voyage, and their relative apparatuses of representation.” She continues,

In many ways, their filmic image partakes in a form of tourism: cinema’s depiction is both an extension and an effect of the tourist’s gaze. Repeatedly traversed and re-created by the camera, Naples and New York have produced a real tourism of images. Shot over and over again, these cities have become themselves an image, imagery, a picture postcard.

The public’s impulse to shoot the city is encouraged by the constant replicas of the city depicted in film and television, leading us to see the city from the lens of a viewfinder.