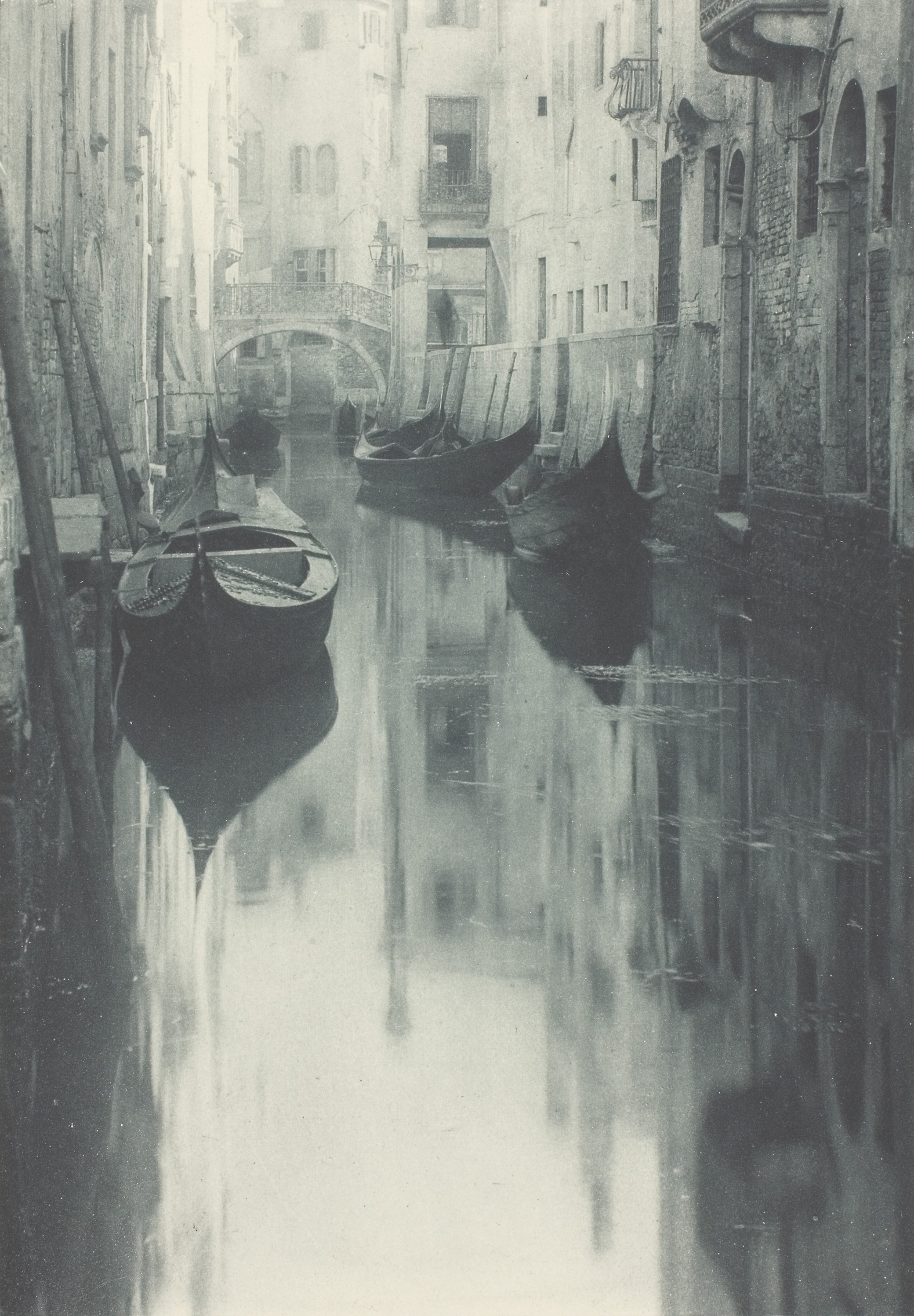

Reflection-Venice, by Alfred Stieglitz, c. 1897. Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Daniel, Richard, and Jonathan Logan.

In the weeks ahead, as the world continues to reckon with and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories dealing with quarantine, unfathomable deaths, isolation, dread, and attempts to find community when the rest of the world feels far away.

Thomas Mann described his 1912 novella Death in Venice as “a story of death…of the voluptuousness of doom.” The story follows the writer Gustav von Aschenbach on his vacation to Venice, where his descent into depravity and eventual death mirrors that of the city itself, overcome by an outbreak of cholera.

Aschenbach originally planned to leave Venice not long after he arrived, but he could not bring himself to quit the place that housed the object of his obsession: a young Polish boy named Tadzio to whom he has never spoken. When the train station loses his luggage, he takes it as a sign that he should stay and continue to watch and follow Tadzio—despite the fact the city’s hot and humid climate seemed detrimental to his health even before he begins to hear rumors of a pestilence. In the excerpt below, adapted from the translation by Kenneth Burke first published serially in The Dial in 1924, Aschenbach finally learns the threat the city poses. He considers telling Tadzio’s mother about the outbreak so that she may leave the city and save her family. He decides instead to stay silent and remain in Venice.

During his fourth week at the Lido Gustav von Aschenbach made several sinister observations touching on the world about him. First, it seemed to him that as the season progressed the number of guests at the hotel was diminishing rather than increasing; and German especially seemed to be dropping away, so that finally he heard nothing but foreign sounds at table and on the beach. Then one day in conversation with the barber, whom he visited often, he caught a word which startled him. The man had mentioned a German family that left soon after their arrival; he added glibly and flatteringly, “But you are staying, sir. You have no fear of the plague.” Aschenbach looked at him. “The plague?” he repeated. The gossiper was silent, made out as though busy with other things, ignored the question. When it was put more insistently, he declared that he knew nothing, and with embarrassing volubility he tried to change the subject.

That was about noon. In the afternoon there was a calm, and Aschenbach rode to Venice under an intense sun. For he was driven by a mania to follow the Polish children whom he had seen with their governess taking the road to the steamer pier. He did not find the idol at San Marco. But while sitting over his tea at his little round iron table on the shady side of the square, he suddenly detected a peculiar odor in the air that, it seemed to him now, he had noticed for days without being consciously aware of it. The smell was sweetish and drug-like, suggesting sickness and wounds and a suspicious cleanliness. He tested and examined it thoughtfully, finished his luncheon, and left the square on the side opposite the church. The smell was stronger where the street narrowed. On the corners printed posters were hung, giving municipal warnings against certain diseases of the gastric system liable to occur at this season, against the eating of oysters and clams, and also against the water of the canals. The euphemistic nature of the announcement was palpable. Groups of people had collected in silence on the bridges and squares; and the foreigner stood among them, scenting and investigating.

At a little shop he inquired about the fatal smell, asking the proprietor, who was leaning against his door surrounded by coral chains and imitation amethyst jewelry. The man measured him with heavy eyes, and brightened up hastily. “A matter of precaution, sir!” he answered with a gesture. “A regulation of the policy which must be taken for what it is worth. This weather is oppressive, the sirocco is not good for the health. In short, you understand—an exaggerated prudence perhaps.” Aschenbach thanked him and went on. Also on the steamer back to the Lido he caught the smell of disinfectant.

Returning to the hotel, he went immediately to the periodical stand in the lobby and ran through the papers. He found nothing in the foreign-language press. The domestic press spoke of rumors, produced hazy statistics, repeated official denials and questioned their truthfulness. This explained the departure of the German and Austrian guests. Obviously, the subjects of other nations knew nothing, suspected nothing, were not yet uneasy. “To keep it quiet!” Aschenbach thought angrily as he threw the papers back on the table. “To keep that quiet!” But at the same moment he was filled with the satisfaction over the adventure that was to befall the world about him. For passion, like crime, is not suited to the secure daily rounds of order and well-being; and every slackening in the bourgeois structure, every disorder and affliction of the world, must be held welcome, since they bring with them a vague promise of advantage. So Aschenbach felt a dark contentment with what was taking place, under cover of the authorities, in the dirty alleys of Venice. This wicked secret of the city was welded with his own secret, and he too was involved in keeping it hidden. For in his infatuation he cared about nothing but the possibility of Tadzio’s leaving, and he realized with something like terror that he would not know how to go on living if this occurred.

Lately he had not been relying simply on good luck and the daily routine for his chances to be near the boy and look at him. He pursued him, stalked him. On Sundays, for instance, the Poles never appeared on the beach. He guessed that they must be attending mass at San Marco. He hurried there; and stepping from the heat of the square into the golden twilight of the church, he found the boy he was hunting, bowed over a prie-dieu, praying. Then he stood in the background, on the cracked mosaic floor, with people on all sides kneeling, murmuring, and making the sign of the cross. The compact grandeur of this oriental temple weighed heavily on his senses. In front, the richly ornamented priest was conducting the office, moving about and singing; incense poured forth, clouding the weak little flame of the candle on the altar—and with the sweet, stuffy sacrificial odor another seemed to commingle faintly: the smell of the infested city. But through the smoke and the sparkle Aschenbach saw how the boy there in front turned his head, hunted him out, and looked at him.

When the crowd was streaming out through the opened portals into the brilliant square with its swarm of pigeons, the lover hid in the vestibule; he kept under cover, he lay in wait. He saw the Poles quit the church, saw how the children took ceremonious leave of their mother, and how she turned toward the piazzetta on her way home. He made sure that the boy, the nunlike sisters, and the governess took the road to the right through the gateway of the clock tower and into the Merceria. And after giving them a slight start, he followed, followed them furtively on their walk through Venice. He had to stand still when they stopped, had to take flight in shops and courts to let them pass when they turned back. He lost them; hot and exhausted, he hunted them over bridges and down dirty blind alleys—and he underwent minutes of deadly agony when suddenly he saw them coming toward him in a narrow passage where escape was impossible. Yet it could not be said that he suffered. He was drunk, and his steps followed the promptings of the demon who delights in treading human reason and dignity underfoot.

In one place Tadzio and his companions took a gondola; shortly after they had pushed off from the shore, Aschenbach, who had hidden behind some structure while they were climbing in, now did the same. He spoke in a hurried undertone as he directed the rower, with the promise of a generous tip, to follow unnoticed at a distance the gondola that was just rounding the corner. And he thrilled when the man, with the roguish willingness of an accomplice, assured him in the same tone that his wishes would be carried out, carried out faithfully.

Leaning back against the soft black cushions, he rocked and glided toward the other black-beaked craft where his passion was drawing him. At times it escaped; then he felt worried and uneasy. But his pilot, as though skilled in such commissions, was always able through sly maneuvers, speedy diagonals, and shortcuts to bring the quest into view again. The air was quiet and smelly, the sun burned down strong through the slate-colored mist. Water slapped against the wood and stone. The call of the gondolier, half warning, half greeting, was answered with a strange obedience far away in the silence of the labyrinth. White and purple umbels with the scent of almonds hung down from little elevated gardens over crumbling walls. Arabian window casings were outlined through the murkiness. The marble steps of a church descended into the water; a beggar squatted there, protesting his misery, holding out his hat, and showing the whites his eyes as though he were blind. An antiquarian in front of his den fawned on the passerby and invited him to stop in the hopes of swindling him. That was Venice, the flatteringly and suspiciously beautiful—this city, half legend, half snare for strangers; in its foul air art once flourished gluttonously, and had suggested to its musicians seductive notes that cradle and lull. The adventurer felt as though his eyes were taking in this same luxury, as though his ears were being won by just such melodies. He recalled too that the city was diseased and was concealing this through greed—and he peered more eagerly after the retreating gondola.

In his infatuation, he wanted simply to pursue uninterrupted the object that aroused him, to dream of it when it was not there, and, after the fashion of lovers, to speak softly to its mere outline. But at the same time, selfish and calculating, he turned his attention to the unclean transactions here in Venice, this adventure of the outer world that conspired darkly with his own and that fed his passion with vague lawless hopes.

Bent on getting reliable news of the condition and progress of the pestilence, he ransacked the local papers in the city cafés, as they had been missing from the reading table of the hotel lobby for several days now. Statements alternated with disavowals. The number of the sick and dead was supposed to reach twenty, forty, or even a hundred and more—and immediately afterward every instance of the plague would be either flatly denied or attributed to completely isolated cases that had crept in from the outside. There were scattered admonitions, protests against the dangerous conduct of foreign authorities. Certainty was impossible. One day at breakfast in the large dining hall he entered into a conversation with the manager, that softly treading little man in the French frock coat who was moving amiably and solicitously among the diners and had just stopped at Aschenbach’s table for a few passing words. Just why, the guest asked negligently and casually, had disinfectants become so prevalent in Venice recently? “It has to do,” was the evasive answer, “with a police regulation, and is intended to prevent any conveniences or disturbances to the public health that might result from the exceptionally warm and threatening weather.” “The police are to be congratulated,” Aschenbach answered; and after the exchange of a few remarks on the weather, the manager left.

The following day, in the afternoon, Aschenbach walked from the Piazza San Marco into the English travel bureau located there; and after changing some money at the cash desk, he put on the expression of a distrustful foreigner and launched his fatal question at the attendant clerk. He began, “No reason for alarm, sir. A regulation without any serious significance…” But as he raised his blue eyes, he met the stare of the foreigner, a tired and somewhat unhappy stare focused on his lips with a touch of scorn. Then the Englishman blushed. “At least,” he continued in an emotional undertone, “that is the official explanation, which people here are content to accept. I will admit that there is something more behind it.” And then in his frank and leisurely manner he told the truth.

For several years now Indian cholera had shown a heightened tendency to spread and migrate. Hatched in the warm swamps of the Ganges delta, rising with the noxious breath of that luxuriant, unfit primitive world and island wilderness shunned by humans and where the tiger crouches in the bamboo thickets, the plague had raged continuously and with unusual strength in Hindustan, had reached eastward to China, westward to Afghanistan and Persia, and, following the chief caravan routes, had carried its terrors to Astrakhan and even Moscow. But while Europe was trembling lest the specter continue its advance from there across the country, it had been transported over the sea by Syrian merchantmen, and had turned up almost simultaneously in several Mediterranean ports, had raised its head in Toulon and Malaga, had showed its mask several times in Palermo and Naples, and seemed permanently entrenched through Calabria and Apulia. The north of the peninsula had been spared. Yet in the middle of this May in Venice the frightful vibrios were found on one and the same day in the blackish wasted bodies of a cabin boy and a woman who sold groceries. The cases were kept secret.

But within a week there were ten, twenty, thirty more, and in various sections. A man from the Austrian provinces who had made a pleasure trip to Venice for a few days returned to his hometown and died with unmistakable symptoms—and that is how the first reports of the pestilence in the lagoon city got into the German newspapers. The Venetian authorities answered that the city’s health conditions had never been better, and took the most necessary preventive measures. But probably the food supply had been infected. Denied and glossed over, death was eating its way along the narrow streets, and its dissemination was especially favored by the premature summer heat, which made the water of the canals lukewarm. Yes, it seemed as though the plague had got renewed strength, as though the tenacity and fruitfulness of its stimuli had doubled. Cases of recovery were rare. Out of a hundred attacks, eighty were fatal, and in the most horrible manner. For the plague moved with utter savagery, and often showed that most dangerous form, which is called “the drying.” Water from the blood vessels collected in pockets, and the blood was unable to carry this off. Within a few hours the victim was parched, his blood became as thick as glue, and the stifled amid cramps and hoarse groans. Lucky for him if, as sometimes happened, the attack took the form of a light discomfiture followed by a profound coma from which he seldom or never awakened.

At the beginning of June the pesthouse of the Ospedale Civico had quietly filled; there was not much room left in the two orphan asylums, and a frightfully active commerce was kept up between the wharf of the Fondamenta Nuove and San Michele, the burial island. But there was the fear of a general drop in prosperity. The recently opened art exhibit in the public gardens was to be considered, along with the heavy losses that in case of panic or unfavorable rumors would threaten business, the hotels, the entire elaborate system for exploiting foreigners—and as these considerations evidently carried more weight than love of truth or respect for international agreements, the city authorities upheld obstinately their policy of silence and denial. The chief health officer had resigned from his post in indignation, and been promptly replaced by a more tractable personality. The people knew this; and the corruption of their superiors, together with the predominating insecurity, the exceptional condition into which the prevalence of death had plunged the city, induced a certain demoralization of the lower classes, encouraging shady and antisocial impulses that manifested themselves in license, profligacy, and a rising crime wave. Contrary to custom, many drunkards were seen in the evenings; it was said that at night nasty mobs made the streets unsafe. Burglaries and even murders became frequent, for it had already been proved on two occasions that persons who had presumably fallen victim to the plague had in reality been dispatched with poison by their own relatives. And professional debauchery assumed abnormal and obtrusive proportions such as had never been known here before, and to an extent that is usually found only in the southern parts of the country and in the Orient.

The Englishman pronounced the final verdict on these facts. “You would do well,” he concluded, “to leave today rather than tomorrow. It cannot be much more than a couple of days before a quarantine zone is declared.”

“Thank you,” Aschenbach said, and left the office.

Read the other entries in our series: Heinrich Heine, George Eliot, Samuel Pepys, Willa Cather, Lucretius, Jack London, John Keats, Alessandro Manzoni, Giovanni Boccaccio, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Daniel Defoe, François Rabelais, and Robert Louis Stevenson.