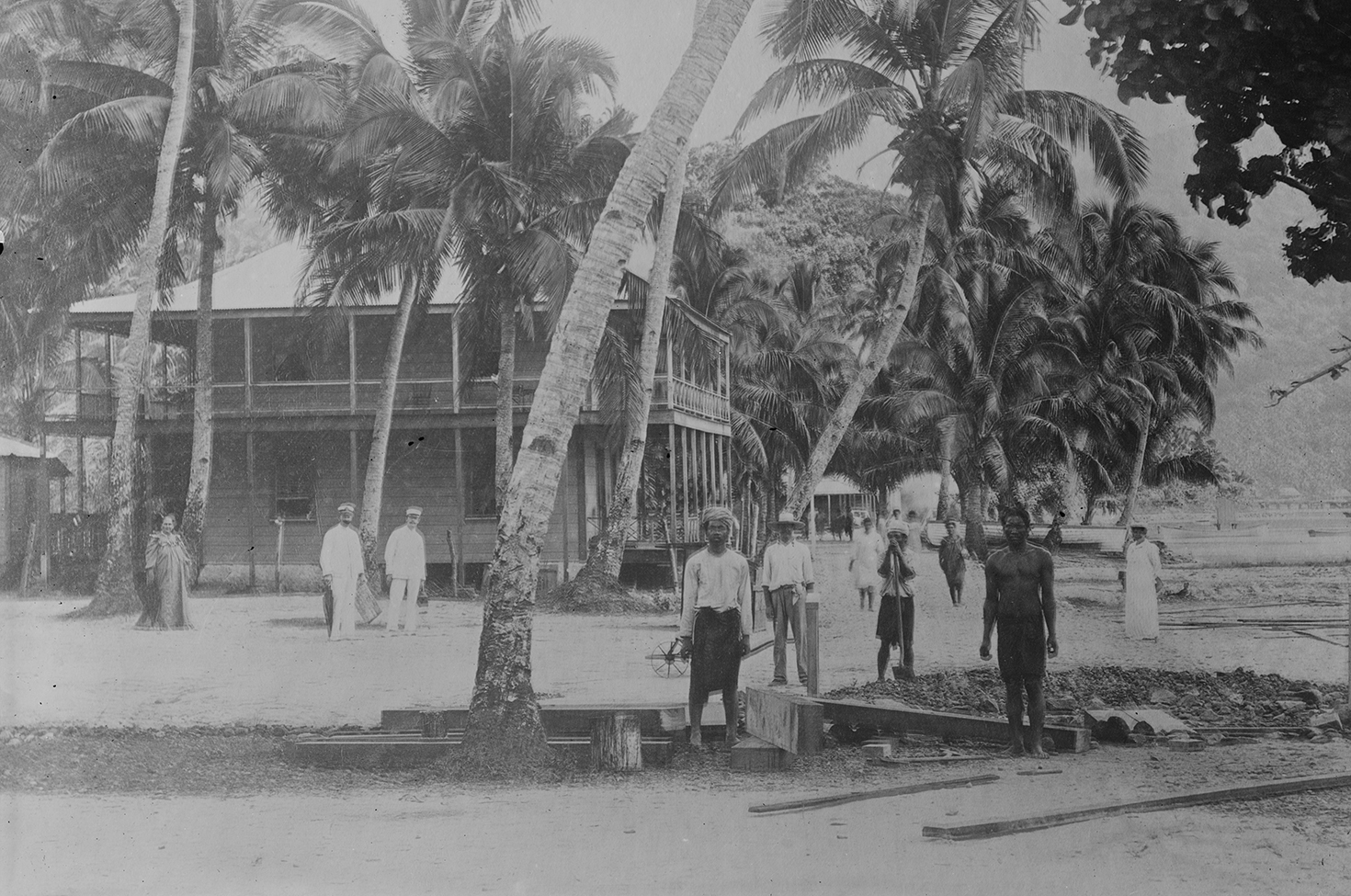

Pago Pago in American Samoa, c. 1918. Photograph by Bain News Service. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Those living in the year 1918 witnessed too much death in a too compressed period of time. War and pandemic had spread so quickly around the globe that life expectancies dropped in developed nations for the first time since the Industrial Revolution. It was even worse for people in less developed nations, where they had little access to care and not much immunity to illnesses from elsewhere. Many young men died on the battlefields of northern France in 1918, but many more people globally died in their beds at home from that year’s deadly strain of the flu.

The U.S. had entered World War I a year earlier, and soldiers were cramming into barracks and bases across the country to prepare for deployment. At Camp Funston in Kansas, fifty thousand doughboys-to-be got acquainted with sharing mess halls, barracks, and every second of their days with one another. By the time those soldiers boarded the ships that would take them to Europe, they were carrying not only the hopes of a nation but also a new strain of influenza that had first been identified at a hospital on the base in 1917. From January 1918 to December 1920 the pandemic flu killed an estimated fifty million people worldwide, possibly the greatest mortality event in human history. Stray dogs feasted on the deceased victims in remote fishing villages in Alaska. In Illinois, space in morgues was so limited that bodies awaiting burial were piled on top of one another.

The flu spread rapidly during the spring of 1918, infecting far more people than influenza typically would at that time of year. The next wave of infections began in September 1918 and had a disproportionately high impact on young and otherwise healthy people. The pandemic came to be known as the Spanish flu not because of its origin; Spain’s neutrality in World War I left it lacking a censor to silence reporting on the outbreak, making Spanish newspapers the first to carry news of the deadly flu.

On September 28, 1918, Philadelphia held the fourth annual Liberty Loan Drive parade to encourage citizens to financially support the Allied war effort by buying government bonds. Two hundred thousand people attended the parade, ready to support the war with their wallets or perhaps just to witness the spectacle. Seventy-two hours later, all thirty-one hospitals in the city were full. The Catholic Church scrambled to create makeshift hospitals, but most infected patients returned home to crowded working-class neighborhoods to cough and die. A week later 2,600 were dead. Two weeks later, the number was 4,500. In Washington, DC, commissioner Louis Brownlow and his Board of Health hijacked two train cars of coffins headed to Pittsburgh and mandated that they be sent to DC hospitals under armed guard. On October 5 the Philadelphia Inquirer urged people to “talk of cheerful things instead of disease.” By the second week of October, death rates in Philadelphia had hit a thousand per day; steam shovels began to dig mass graves when the city could not keep up with the corpses.

In American Samoa, however, nobody died from the pandemic. Thanks to swift action from the governor, the local population was able to avoid the 1918 flu entirely.

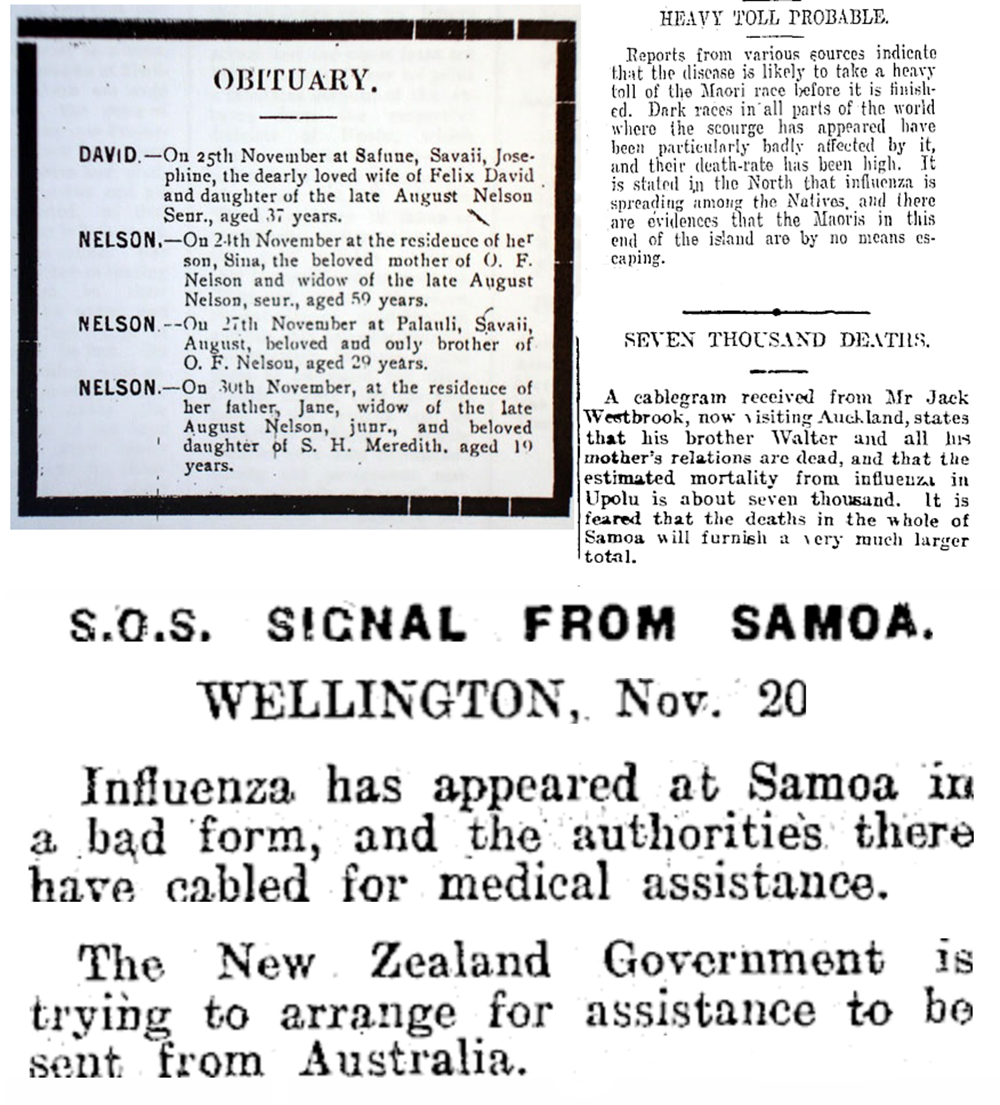

That wasn’t true of Western Samoa, which was about forty miles west from American Samoa and consisted of two large islands, Upolu and Savai’i. Although the populations of both states were culturally the same, sharing a language, culture, and sometimes family ties, the lives of those on each island remained distinct because of colonialism. Western Samoa had been administered by New Zealand since the beginning of World War I. It didn’t shut out the world—and it was devastated by the pandemic. A fifth of the population perished.

The two divergent responses to the flu offer as good of a natural experiment as we are ever likely to see when it comes to whole-country quarantines during pandemics. American Samoa shut out the world and had zero deaths, while at least 8,500 died in Western Samoa. It seems a fairly clear statistical endorsement of quarantine.

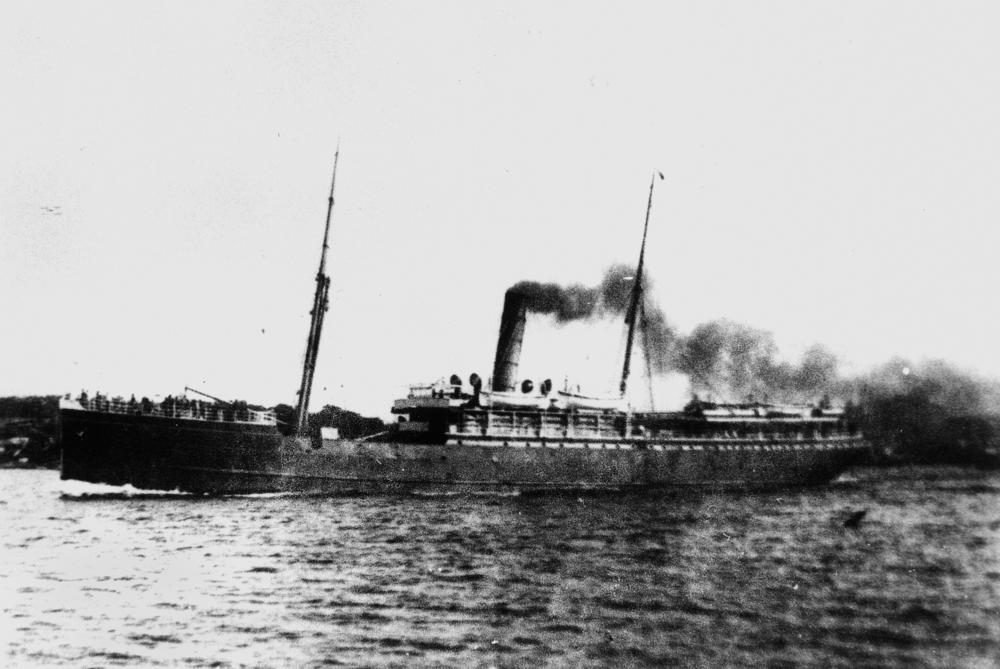

New Zealand was already struggling with the pandemic after ships from elsewhere in the British Commonwealth had carried the contagion from Europe. But although the virus was already spreading, the passenger and cargo ship Talune still departed from Auckland on October 30, 1918. It took off on its usual tour of the Pacific, carrying passengers and mail to Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, and Nauru. Two crew members were already sick when the Talune set out and were left behind in Auckland. By the time the ship arrived in Fiji on November 4, several other crew members were symptomatic.

Although officials in Fiji quarantined the vessel, forcing the crew to stay aboard while asymptomatic locals and cargo were unloaded, the ship received far less of a medical inquisition in Western Samoa, where it arrived on November 7. In Apia, the capital and major port city, the local quarantine officer asked only rudimentary questions of the captain, who downplayed the severity of the symptoms spreading on his ship. The crew lowered the yellow banner flying over the ship, which had indicated its quarantine status since leaving Fiji. Sick passengers disembarked. Within weeks, 22 percent of the population of both islands of Western Samoa was dead. No help arrived until December, when four doctors from Australia landed at Samoa. The pandemic was already fading away, the survivors trying to rebuild.

The U.S. Navy appointed Commander John Martin Poyer to govern American Samoa in 1915. He had retired from active duty in 1906 due to ill health following the loss of his wife. Poyer heard daily wireless broadcasts about the flu but received no official advice about how to protect American Samoa from any virus that might invade. In 1903 the territory had set up a minuscule quarantine station on Goat Island, off the harbor of Tutuila, the main island—a proactive attempt to protect indigenous Samoans, who had never been exposed to diseases common in Europe and the U.S. The station had been used only three times in fifteen years, however, including a measles crisis in 1911.

Knowing this, Poyer made his own plans.

Four days before the Talune dropped anchor in Western Samoa, the SS Sonoma arrived in Pago Pago Harbor from San Francisco via Honolulu. There had been one death and fourteen cases of flu on her voyage. On arrival, the two people who were still sick were placed in the naval dispensary, and the Pago Pago inhabitants returning home were placed under house arrest and their possessions fumigated. Only after days of observation and temperature readings were they allowed to leave.

Poyer quarantined all ships arriving in Pago Pago Harbor, the main port on the north side of Tutuila, and kept passengers under house arrest for five days either on Goat Island in the bay or in the dispensary or hospital. Samoans were held at the hospital whereas white arrivals were quarantined at the dispensary. Such racial boundaries were enforced in public life, even if they were sometimes flouted privately—as was the case with the ban on interracial marriage. Even if U.S. Navy policies were sometimes more popular with indigenous Samoans than the behavior of traders and missionaries from elsewhere, early twentieth-century eugenics dictated a separation of the colonized people from the colonizers, which carried into the enforcement of the blockade against a virus.

There was, unsurprisingly, dissent from the indigenous people concerning the presence of colonial governors. Rule by the U.S. Navy was by no means universally popular; complaints about abuse of power, including a petition signed by over three hundred matais, resulted in the establishment of a U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry aboard the USS Kansas in Pago Pago Harbor in 1920.

Poyer’s style of indirect rule relied heavily on Samoan matais (chiefs), indigenous heads of families who oversaw meetings of district councils, looked out for the welfare of their people, and made important decisions pertaining to the areas under their control. By exerting influence on the matais, Poyer believed he could control the territory at large. He did not disrupt existing authority structures by installing kings, as other colonial powers had done in the area. For the quarantine, Poyer secured the support he needed to make his plan possible. The matais, who even turned away their kinfolk traveling from other islands, were vital to Poyer’s plan to blockade small boat travel and enforce his quarantine. Over on Western Samoa, where there was no such partnership with the government, 45 percent of matais perished due to the flu.

Poyer had ordered that no vessel leave Western Samoa for the American-administered islands until no passengers had been flu patients for ten days. This blockade would have been easy to enforce on large steamers, which had no choice but to land at large, well-monitored ports. Small craft, though, could easily have landed by night were it not for the fierce enforcement of the quarantine by Samoans. Indigenous Samoans patrolled their shores in small boats, keeping contagion away by directing all traffic to Pago Pago. Poyer’s actions would not have been possible without the support of the matais. At first Samoans were upset at being quarantined in the capital city and prevented from going home, but Poyer’s administration feared they would not comply with the rules if they were allowed to return to their homes and self-isolate. So effective were the Samoans enforcement of the quarantine measures that Governor Poyer recommended the three district chiefs of American Samoa—Mauga, Satele, and Tufele—for presidential medals, with Poyer writing that “the fact that no case of influenza broke out in our islands…in no small measure, to the influence exerted over the natives by these chiefs.”

In late November, Colonel Robert Logan, the governor of Western Samoa, sent a small mail boat to Pago Pago to meet a mail steamer traveling around the islands. Poyer, standing in a small boat in the harbor with a megaphone in hand, stopped the vessel Logan had sent and declared it could not come ashore unless its crew submitted to the quarantine he had imposed on all boats from Western Samoa on November 23. The captain then asked if he could come aboard the steamer and put his mail there instead. Poyer’s booming reply made clear that both the territory, and the boat under his jurisdiction in its harbor, would not welcome the mail and pandemic carried from Western Samoa.

Logan was so infuriated at what he saw as a snub from his colleague that he cut off all contact with American Samoa. He later refused medical aid from American Samoa, ignoring Poyer when he wired Logan, “Please inform me if we can be of any service or assistance.” A staff of medical officers and the first graduates of a nursing school set up in 1914 for Samoan women sat waiting for an assignment while thousands died half a day’s sail away in hastily set up hospitals run by local administrators and the garrison’s soldiers, many of whom also fell ill. Logan exercised a more direct style of colonial rule than Poyer. When the principal of the Papauta Girls’ School asked for food for indigenous children, he replied, “Send them food! I would rather see them burning in hell! There is a dead horse at your gate, let them eat that. Great fat, lazy loafing creatures.”

Logan had been an acting colonel in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, which took over administration of the islands after capturing them from Germany in 1914. The Scottish-born former farmhand had little experience in administration and was ill-equipped to handle such a crisis. His rule was sometimes too hands-off but often too interventionist. Crucially he entirely failed to take action to prevent the spread of the pandemic. A 1919 report of the Samoan Epidemic Commission, established by New Zealand to investigate the outbreak, found that “had the temperatures of all the passengers and crew [of the Talune] been taken…no qualified port official could have granted immediate pratique [clearance to enter port due to absence of infectious disease] without being guilty of criminal carelessness.” The inquiry labeled Logan’s refusal of aid from the Americans “hasty,” but his racism and ineptitude were not remarkable for colonial administrators of his era.

Long after the flu died down, families continued to seal themselves inside their homes with thick mats across the doors. When they emerged, their crops were dead after weeks of neglect. Not long after the pandemic, Samoans requested direct rule from London rather than from the British Dominion of New Zealand. The nation would not gain independence until 1962, following the Mau (which means “resolute opinion”) movement’s widespread peaceful resistance to colonial occupation.

The odd thing about public health is that the more effective policies are, the less necessary they seem. Samoa provides us with a rare example of a visible and clearly successful action taken by government and citizens against disease. It is wrong to simply paint the two Samoan flu experiences as examples of different colonial responses. Samoan society is structured by deeply held familial bonds. Without an adherence to those bonds and the swift and decisive action of the matais to set up patrols to ensure a quarantine that would have been unenforceable by a few colonial administrators, thousands more Samoan lives would have been lost.

On June 10, 1919, John Martin Poyer looked out on Pago Pago Harbor for the last time. He received a seventeen-gun salute upon departure. He was later awarded a navy cross “for exceptionally meritorious service in a duty of great responsibility as governor of American Samoa, for wise and successful administration of his office, and especially for the extraordinarily successful measures by which American Samoa was kept absolutely immune from the epidemic of influenza.”

The most touching tribute to Poyer was not the medal or the guns that echoed over the bay as he left the island he had helped save. It was a song that the traders of John Rothschild & Co. of San Francisco, a company that imported spices, cocoa, and chocolate from the South Pacific, heard as they waited in Pago Pago Harbor, sung by the ship’s crew to the tune of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Beginning with the lines “Oi ai le motu i le Pasifika sauté Tutuila ma Upolu / A o Tutuila oi ai fu’a / Meleke, a o Upolu le o Niusilani,” the song translates as:

There are two islands in the South Pacific, Tutuila and Upolu,

Tutuila under the American flag, Upolu that of New Zealand.

God has sent down a sickness on the world,

And all the lands are filled with suffering.

The two islands are forty miles apart,

But in Upolu, the Island of New Zealand, many are dead,

While in Tutuila, the American island, not a one is dead.

Why? In Tutuila they love the men of their villages;

In Upolu they are doomed to punishment and to death.

God in heaven bless the American governor and flag.

If you visit Upolu today, you’ll find a small concrete church on the road to Apia. The churchyard bears a few concrete rectangles in the lawn along with a shiny black marbled plaque reading in sacred memory of the persons who died in the influenza epidemic 1918. That plaque is new, given to the people of Samoa by the government of New Zealand in 2018, upon the centenary of the pandemic. Sixteen years before, Prime Minister Helen Clark had apologized for New Zealand’s colonial mismanagement of Samoa. Once weathered and worn, the plaque has been refurbished by the people of New Zealand. Poyer doesn’t have a memorial, just a simple gravestone in Arlington National Cemetery, but in 1919 Tutuila built a high school to educate the children saved by the decisive action that he and the Matai took. It was named the Poyer School.