Ophelia, by Sir John Everett Millais, c. 1851. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

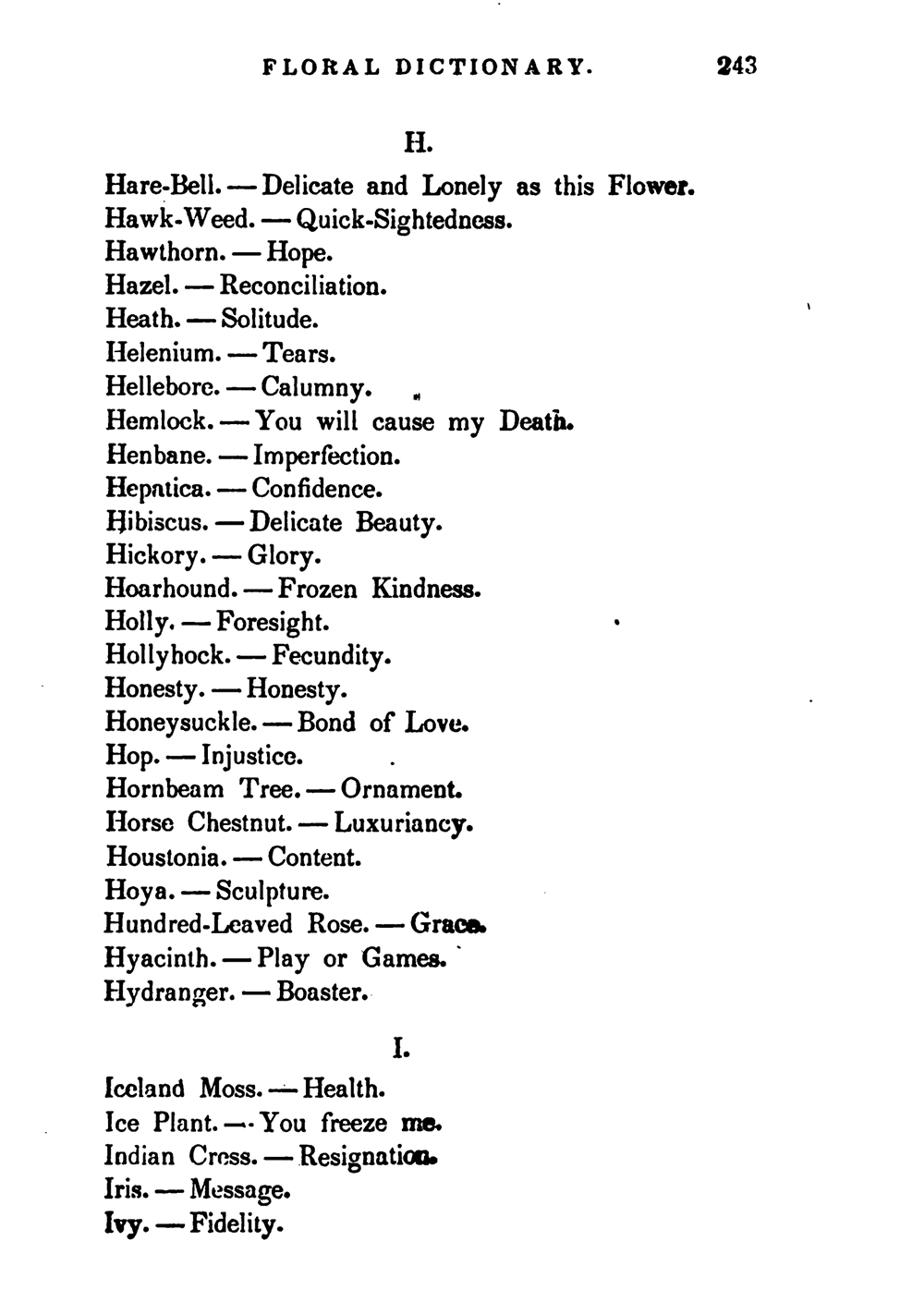

Ophelia, gone mad and singing to herself, paces through the halls of Elsinore in Act IV of Hamlet, a bouquet in her hand for the king and queen. It includes rosemary, pansies, fennel, rue, columbines, and a daisy. An upper-class American or European woman watching the play during the nineteenth century would have had no trouble understanding the message Ophelia meant to send with her offering: rosemary for remembrance, pansies for thoughts, fennel for strength, rue for disdain, columbines for folly, and that lone daisy for innocence. Ophelia became something of an obsession of the era, as the Pre-Raphaelites embraced her as a symbol of romantic love and femininity. John Everett Millais’ 1852 painting was just one of many to depict Hamlet’s lover: the beautiful pale girl, palms upturned, floating in a stream of willows (mourning), violets (faithfulness), and poppies (sleep). Where a modern audience might see only flowers—or a girl who had drifted away from sanity—the Victorians saw a rich tapestry of meaning.

The drama of a coded flower message wasn’t confined to the stage or to art for women of the time; it played out in their own romances and daily lives through the fashionable trend of floriography, the language of flowers. The fad of sending secret missives to lovers and friends via intricate bouquets was one of the few modes of expression available to these women.

“Life for Victorian women was constrained by husbands’ and society’s expectations, and there were few opportunities for self-expression, let alone career building,” Jacqueline Banerjee, a British historian and editor of the site Victorian Web, told me via email. “Anything to do with flowers was an acceptable hobby, though, and some did manage to take it further through craftwork, design, and painting—and studying botany seriously as a science.”

This fad exploded in the early nineteenth century when a series of travel letters from Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, a poet married to a British ambassador to Turkey, were published in 1763 following her death. Like many Brits at the time, Montagu became fascinated with all things from the world east of Europe. She brought back to England an amalgamated version of several Turkish traditions, including a mode of communication used by harem girls to send each other messages in code via flowers. Describing the practice, she wrote:

There is no color, no flower, no weed, no fruit, herb, pebble, or feather, that has not a verse belonging to it; and you may quarrel, reproach, or send letters of passion, friendship, or civility, or even of news, without ever inking your fingers.

Montagu wasn’t the only one to find floriography sexy and exotic; soon members of Orientalist circles throughout Europe were sending each other messages, as Romie Stott reported for Atlas Obscura in 2016.

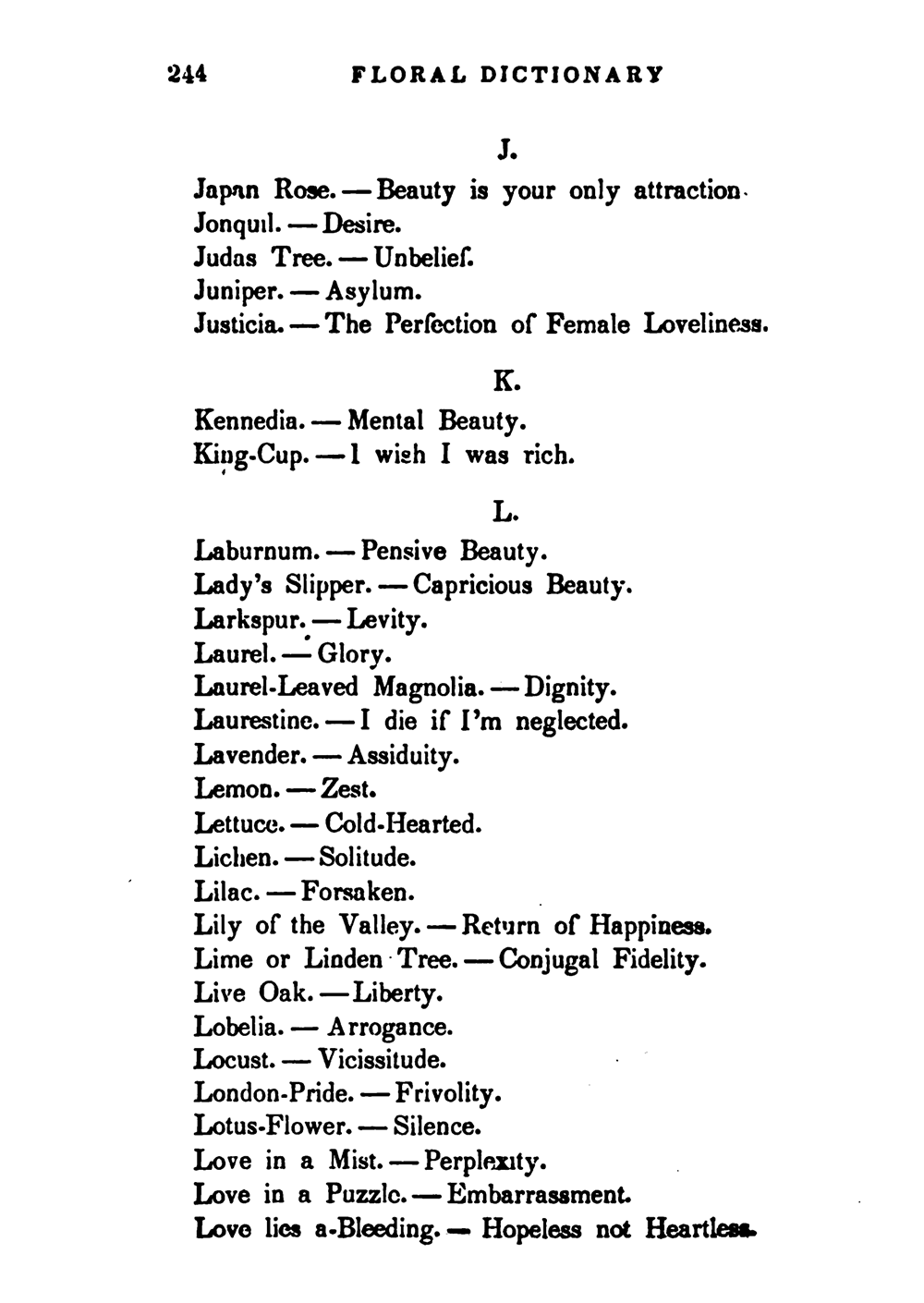

A proliferation of flower dictionaries expanded this language. These reference works were a mix of the descriptive and the prescriptive: they at once codified existing knowledge around flower meanings while also setting down new (and sometimes contradictory) meanings. One of the first major texts was a French volume published in 1819 called Le Langage des fleurs (The Language of Flowers). It was soon translated into English and became popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Floriography was so prevalent in the U.S. that between 1827 and 1923 fashionable young ladies could choose between some ninety-eight flower dictionaries or read up on the latest floriography news in Harper’s Magazine and The Atlantic, according to Stott.

Well-bred women of the nineteenth century would devote hours to the cultivation of their gardens, often searching for the rarest flower. The 1800s saw the rise of orchidelirium, an obsession with orchids. Rich Victorians would pay thousands of dollars to send special hunters on remote treks in order to obtain hard-to-find species in the wild. The fever to acquire unusual flowers even blossomed into mania, with orchid hunters driven to dueling and even murder in the quest for the rarest orchids in the world.

Some women of the day made important contributions to botany as a science, including the beloved children’s author and illustrator Beatrix Potter. From her garden in northern England, she devoted hours and hours to the study of fungi, eventually completing some 350 highly accurate drawings for scientific use.

With the rise of greenhouse technology in the early 1800s, wealthy women could grow dozens, if not hundreds, of flowers to craft their complex messages. To her lover, a woman could send violet-colored amaranths, also known as the love-lies-bleeding flower, in order to convey the sentiment “I am hopeless but not heartless.” The suitor might reply with a bouquet of orange blossoms to say, “Your purity equals your loveliness,” or American cowslips for “My darling, you are my divinity.” Some have compared these messages to fragrant emoji, but they were subtler than today’s icons, more disguised than the message of a bright smiley face or a waving hand. Their role in society required insider knowledge, akin to a secret code.

Floriography wasn’t for romance alone. Women also would send bouquets to one another to express love and affection or to fight with their female friends. Flower dictionaries of the era list dozens of different types of flowers conveying the meaning “friendship.” There was arbor vitae for unchanging friendship, oak-leaved geranium for true friendship, and blue periwinkle for early friendship. For less warm relationships, belvedere meant “I declare against you” and coltsfoot warned, “Justice shall be done.”

Victorians may have been well-versed in floriography, but they didn’t invent it. “We tend to think of the language of flowers beginning in England in the Victorian era, but the notion has been around for many, many more years than that in many countries,” said Brenda Kleager, author of Secret Meanings of Flowers.

For instance, in the medieval era women in England began carrying nosegays, or small sprays of flowers to hold under their noses in order to mask the stench of unsanitary city streets. Because women were almost always carrying these mini bouquets, also known as tussie-mussies, they transformed over time into a way for men and women to communicate in passing. By the nineteenth century, a bouquet held upside down signaled a lack of interest, and a flower in one’s hair said, “I like you, but I’m not sure.”

Female novelists delved into the language of flowers as well. Jane Austen, who cultivated her own gardens throughout her life, embedded numerous flower and garden scenes rife with symbolic meaning into her books. The Darcy family’s sprawling gardens at Pemberley in Pride and Prejudice reveal a new softness and romantic side of Mr. Darcy to Elizabeth, while gardens often serve as a measuring stick of character in Northanger Abbey—the protagonist is described within the first paragraph as uninterested in gardening and flowers, save for “the pleasure of mischief.” Later nineteenth-century writers, including the Brontë sisters, followed suit. After the deaths of Catherine and Heathcliff in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Cathy uproots the black currant trees on the overgrown estate to replace them with tidy flowerbeds. Brontë’s intent remains open to interpretation, but her contemporary female readers, nearing the end of a story of lost love, would have easily discovered that currant means “Thy frown will kill me.”

Despite the surface-level frivolity, floriography was serious business, particularly for women: it represented one of the only modes of communication that allowed the expression of intimate matters in a repressive culture, especially when it came to matters of love, friendship, and flirtation. The Victorian era is now infamous for its strict social rules, with an emphasis on repressing sexuality. Dinner parties, social calls, and courtship followed a stringent set of regulations from which forks to use and what time to make a social call to who should stand and who should follow when a person leaves a room, all of which gave women little agency.

Society demanded that women defer to men, contain their emotions, and perhaps above all abide by a degree of silence. Etiquette books from the time instructed women to “cultivate a soft tone of voice and a courteous mode of expression,” advising, “It is better to say too little than too much in company.” In floriography, women could communicate more difficult emotions or thoughts, such as those between courting lovers or quarreling friends—all while guarding the plausible deniability of misinterpretation. The dictionaries provided insight into this private world, but given the variance across texts and the thousands of different flower meanings, women were free to reject how recipients interpreted their messages.

Communication through flowers was a delicate, easily misunderstood art. Even the placement of a bow on the right or left side of a bouquet could indicate interest or disinterest, explains Kleager. Disagreement between flower dictionaries caused confusion, and the subtle vagueness of a bouquet gave its creator leeway. A striped carnation could mean an invitation to a dance—or, according to at least one flower dictionary, that same flower might also mean “refusal.” Bouquets themselves have no syntax, so to speak, lending even more complexity to what order the flowers should be “read” and adding multiple ways to interpret a single bouquet.

Women were able to consider the various implications of a certain bouquet among friends. Say a young man was attempting to court a lady, for example. He might send her a bouquet of bluebells, convolvulus, and white Dittany of Crete. The recipient of the gift might grab the hand of her best friend and rush up to her room to pore over her flower dictionary. If they had Kate Greenaway’s Language of Flowers, they would discover that bluebells symbolized constancy and the White Dittany of Crete was for passion, but the convolvulus could pose a problem. Pink convolvulus signaled tender affection, but convolvulus major might mean the lady had not quite expressed reciprocation, and her suitor was choosing to send a message of “extinguished hopes.”

There were myriad such double meanings or altered implications based on color alone. A red chrysanthemum meant “I love,” but a yellow one spoke of “slighted love.” Greenaway’s flower dictionary lists ten different types of geranium; depending on the color, the flower could mean anything from “melancholy” to “true friendship” to “steadfast piety.”

The greater the number of flowers in the bouquet, the larger the capacity for complexity and confusion, according to Kleager. A single bouquet might convey messages as complex as “I’m interested in you, but I’m not sure,” or “I can’t live without you; please marry me.”

This reflects the human condition more accurately than a straightforward declaration of love: the vagueness of flowers belies a more truthful expression of how confusing and inconstant feelings can be. The essence of floriography itself might have been expressed through a simple bouquet: spruce pine for hope in adversity, penciled geranium for ingenuity, and coriander for hidden worth.