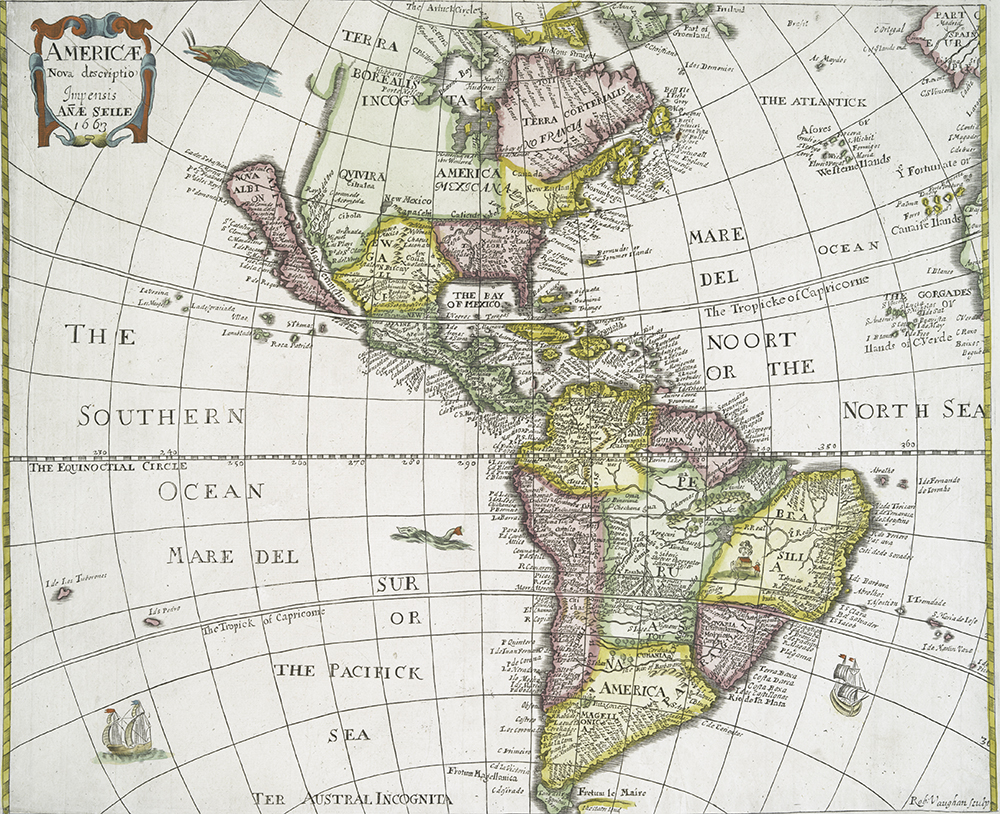

America septentrionalis, by Hendrik Hondius, seventeenth century. The New York Public Library, Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division.

Preceding the arrival of the first colonists in Jamestown, Isabel de Olvera helped to settle what would become the United States. In 1600 she participated in a Spanish expedition from Mexico to New Mexico. Predating the Enlightenment tracts that would fuel the Age of Revolution two centuries later, Olvera employed the language of citizenship and civil law to assert and defend her rights before setting out:

As I am going on the expedition to New Mexico and have some reason to believe that I may be annoyed by some individual since I am a mulatto, and as it is proper to protect my rights in such an eventuality by an affidavit showing that I am a free woman, unmarried, and the legitimate daughter of Hernando, a negro, and an Indian named Magdalena, I therefore request your grace to accept this affidavit, which shows that I am free and not bound by marriage or slavery. I request that a properly certified and signed copy be given to me in order to protect my rights, and that it carry full legal authority. I demand justice.

Olvera’s deposition encapsulates several fundamental truths of American history. First, people of African descent were among the earliest settlers of the Americas, including what is today the United States. Beginning before the arrival of the English, black people helped to found American towns from Santa Fe to St. Augustine, Manhattan to Los Angeles, and from Buenos Aires, Argentina, to Birchtown, Canada. Second, the roots of the twentieth-century American civil rights movement can be traced to the first Africans in the Americas and their succeeding generations throughout the hemisphere. Third, Olvera was of mixed race, as would be her descendants; she embodies the demographic reality that American family trees are founded on mixed-race roots.

Afro-American slavery in the seventeenth century was still relatively small-scale, and as a legal, social, and racial status, slavery was quite variable and inchoate; thus, in the 1600s people of African descent, both free and bond, played a wide variety of roles in the establishment of American societies. Black settlers and soldiers continued to shape American development, and Afro-Americans were among the New World’s earliest scholars, assemblymen, merchants, military officers, physicians, and planters. Like Olvera, many seventeenth-century Afro-Americans were freedom seekers.

While free people of color participated widely in colonial American societies, enslaved individuals contributed to their communities as laborers and domestics and also as artisans and agents, property holders and entrepreneurs, parents and partners. Enslaved residents of seventeenth-century Virginia, Maryland, New York, South Carolina, Florida, Barbados, Mexico, Peru, Cuba, Colombia, Ecuador, and Brazil sought their rights to freedom and property with petitions in colonial courts, with appeals to and as clerical authorities, and in colonial militias. In the seventeenth century, Caribbean populations were largely comprised of enslaved Americans, many of whom regularly challenged slavery through organized revolt, establishing a tradition of armed initiatives for freedom that in the eighteenth century directly precipitated the end of slavery and the rise of freedom in the Americas.

Around 1650, Thomas Hobbes famously declared life nasty, brutish, and short. For the early seventeenth-century residents of the English colony of Virginia, most of whom had arrived from Europe as indentured servants, this was decidedly so. In England, where political policies displaced peasant farmers and targeted Irish Catholics, thousands of men and women were voluntarily or involuntarily bound as servants to New World planters for a finite term (usually three to seven years). In British America, mortality rates initially were so high that it made more economic sense to spend a smaller amount for a temporary servant than to make a large investment in a lifetime slave. In Barbados, Britain’s first plantation colony in the Americas, it was cheaper still to force kidnapped English and Irish indigents to grow tobacco. The first Africans in Virginia were generally treated as indentured servants.

While the 1600s would see the first attempts to define slavery as a legal category and black slaves would eventually displace white servants, European indentures were the primary source of labor in the mainland English colonies until the early 1700s. Indentured servitude and a small but steady trade in Native American slaves persisted into the eighteenth century. In 1671 one official estimated that Virginia had two thousand black slaves and six thousand “Christian servants.” In Maryland, English and Irish servants outnumbered African servants until the 1690s. Both Virginia and Maryland had free populations of color. When “Antonio a Negro” arrived in the Virginia colony in 1621, he was among the first Africans in mainland British America. Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in what would become the United States, was founded in 1607, a year after the first recorded birth of an Afro-American child in Spanish Florida. After serving a term of service alongside indentured servants from the British Isles, Anthony Johnson, as he had become known, married an African woman known as Mary, established five headrights (claims on land established by working it, typically by importing indentured servants), and acquired 250 acres.

In 1683 an Afro-American militia was officially established to help defend the Spanish territory in Florida from English encroachment; this was the first black militia in what would become the United States. Spain’s European rivals and their pirate proxies stimulated the arming of Afro-Spaniards throughout the hemisphere. A roster from 1673 lists some two thousand African-descended soldiers serving in Central American infantries. The royal order to the governor of New Spain to create additional free black companies noted “the mulattos and blacks who defended [Spain’s] circum-Caribbean realms were ‘persons of valor’ who fought with ‘vigor and reputation.’ ” Black militias were formed in Hispaniola, Veracruz, Campeche, Puerto Rico, Panama, Caracas, and Cartagena in addition to Florida. In many cases, these militias were called upon to subdue maroons, but in Florida the Afro-Spanish soldiers were maroons.

The prospect of additional Afro-Spanish soldiers was a principal reason why, in 1693, Spain’s Charles II offered sanctuary in Florida to fugitive slaves arriving from English colonies. The Spanish government freed these individuals, granted them homesteads, and endorsed the election of black political and military leaders. In the 1730s, the Spanish officially transformed this de facto maroon community into a sanctioned free black town outside of St. Augustine and recognized its free black leader, Francisco Menendez. The success of Menendez, a fugitive slave from South Carolina, and the powerful maroon communities of Florida contributed to the initiation of the 1739 Stono Revolt and the Age of Revolution.

In addition to Florida, Africans helped to populate and defend Spanish towns throughout the American Southwest. By 1680, eighty years after Isabel de Olvera’s deposition, the African, Native American, and European mixed-race population of New Mexico had reached almost three thousand.

One of these residents, the Angolan-born Sebastian Rodriguez Brito, served as a military drummer for two of New Spain’s governors there in the 1690s; he ultimately became a man of means and one of the first property owners in colonial Santa Fe. Brito’s son was among the twelve black founders of Las Trampas, New Mexico. Afro-Americans were also among the original Spanish settlers and defenders of towns like Albuquerque and Tucson.

In the seventeenth century, numerous Afro-Brazilians endeavored to secure and advance freedom through their military service to the Portuguese Crown. During Brazil’s wars to recover the region of Pernambuco from an eight-year Dutch occupation in the 1630s, a principal army was composed of free colored men and fugitive slaves under the leadership of the free Afro-Brazilian Henrique Dias. The first Afro-American militia in Peru was formed in 1615. Free black soldiers played significant roles from Cuba’s establishment in the 1500s through its independence wars at the end of the nineteenth century. Afro-Cubans built Cuba’s fortifications and defended the island against competing European powers, pirates, and indigenous settlers; they also assisted campaigns in Florida, including aiding the Patriots during the American Revolution.

In Saint Domingue, former slaves founded a black militia at the turn of the seventeenth century. Several former slaves were granted freedom for their service during a French raid on Cartagena in 1697. Among them was Vincent Olivier, who was captured in battle and taken to Europe, ransomed, met the king of France, and fought with the French army in Germany. Returning to Saint Domingue, Olivier was appointed captain-general of the free black militia, dined with the governor, and was awarded a pension. Olivier’s former colleague and business partner, Etienne Auba, was another prominent black militia captain, whose daughter married a lieutenant of Saint Domingue’s black militia. Two of Olivier’s grandsons fought in the American Revolution. The service of Afro-Americans in colonial militias illustrates not only their role in defending the rights of American colonists around the hemisphere but also how they perceived their own claims to rights and citizenship. At the outset of the French Revolution, per historian John D. Garrigus, “across Saint-Domingue in 1789, free people of color identified militia service as their most important contribution to colonial civil life.”

While African Americans have participated in virtually every military contest in U.S. history, their service was repeatedly constrained by law and/or custom. Regardless of official prohibitions, African Americans continually risked their lives to defend U.S. interests during wartime, despite the fact that their service to their country did not always confer the rights of citizenship.

When military service in defense of a colonial power could not offer a reliable route to freedom, many Afro-Americans found that taking up arms against the state could. Having fought for liberty and independence for decades, Gaspar Yanga, a powerful maroon leader of a fugitive slave community outside of Veracruz, Mexico, negotiated a treaty with the Spanish government in 1618. A predominantly black town, “officials in Veracruz,” according to writer John McNish Weiss, “often had to rely on the more numerous persons of color to fill roles normally held by Spaniards.” For three decades, Yanga had administered and defended a maroon community in multiple sites outside of the port city against colonial combatants (including Afro-Spaniards). The 1618 treaty between Yanga and the Spanish government established the first officially designated free black town in North America: San Lorenzo de los Negros de Cerralvo. With the roots of the town stretching back to the 1570s, some have deemed Yanga “the first liberator of the Americas.” In 1769, Afro-Mexican maroons were again granted the right to establish an independent town.

Africans established independent maroon communities throughout New Granada—the regions that would become known as Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, and Colombia, the latter being the colonial seat. Cartagena, a city that by the seventeenth century was home to significantly more Africans than Europeans, was surrounded by several maroon settlements or palenques. Among these was Matudere, founded around 1681 by fugitive slaves Domingo and Juana Padilla as a refuge for escaped slaves, Amerindians, and others. Though the settlement lasted only twelve years, “In its political, military, and social organization, Matudere resembled what Spaniards would have recognized as an ordered polity, and Domingo and Juana’s authority over diverse ethnolinguistic factions within their camps was similar to that exercised by Spaniards in their own multicultural cities,” per historian Jane Landers. It was perhaps no accident that Juana insisted on being referred to as vice queen, a position unique to the viceroyalties of Peru and New Spain. At that time, New Granada’s highest Spanish official was only a governor, who himself led the raid to destroy the maroon settlement in 1693.

Spanning most of the seventeenth century, Brazil’s Palmares was the largest independent maroon state in the Americas. Brazil received more enslaved Africans than anywhere else in the Americas—approximately four and a half million people. Fugitive communities began with the first arrivals of slaves in the 1530s, and Brazil was the last country in the Western Hemisphere to end institutional slavery in 1888. Most fugitive slave communities in Brazil (often called macombos or quilombos) were composed of tens or sometimes hundreds of residents, somewhat isolated though often with access to a larger commercial center. Some quilombos were relatively short-lived while others have endured, with the descendants of their founders, until the present; in 1988, Brazil’s constitution officially recognized quilombo land rights. Founded in 1605, Palmares encompassed some twenty thousand inhabitants at its peak. It was a unique political confederation of multiple maroon towns with elected officials, taxes, and a central government, where fugitive slaves, as well as some indigenous and European persons, found refuge. Ganga Zumba, a captured Angolan nobleman who freed himself from a sugar plantation, headed the confederation politically and militarily, alternately fighting and negotiating with the colonial state. His nephew Zumbi, was born free in Palmares in 1655, kidnapped as a child, and placed with a missionary with whom he studied Portuguese and Latin. Zumbi was able to make his way back to Palmares at age fifteen and eventually succeeded his uncle. Legend has it that during a stalemate, the colonial state offered to recognize the runaway slaves in the confederation as free, but Zumbi refused the treaty because it did not free all Brazilians. After decades of continuous attempts to conquer the maroon state, Portuguese authorities raised a highly specialized army that ultimately defeated Palmares in 1695. Although several smaller maroon settlements continued to survive in the region, the centralized state did not.

In the seventeenth century, Afro-Americans sought to expand their autonomy using the courts, developing homesteads, serving in the military, forming independent communities, or negotiating with the state. All those endeavors offer a window onto a world of people of African descent whose actions undermined slavery and underscored the Enlightenment ideals of justice and liberty, even before the Enlightenment made these ideals fashionable. Isabel de Olvera’s descendants—and those of all the early African arrivals—“live on,” as historian Peter Wood puts it, “in all the races of…America.”

Excerpted from American Founders: How People of African Descent Established Freedom in the New World by Christina Proenza-Coles. Published by NewSouth Books. Copyright © 2019 by Christina Proenza-Coles. All rights reserved.