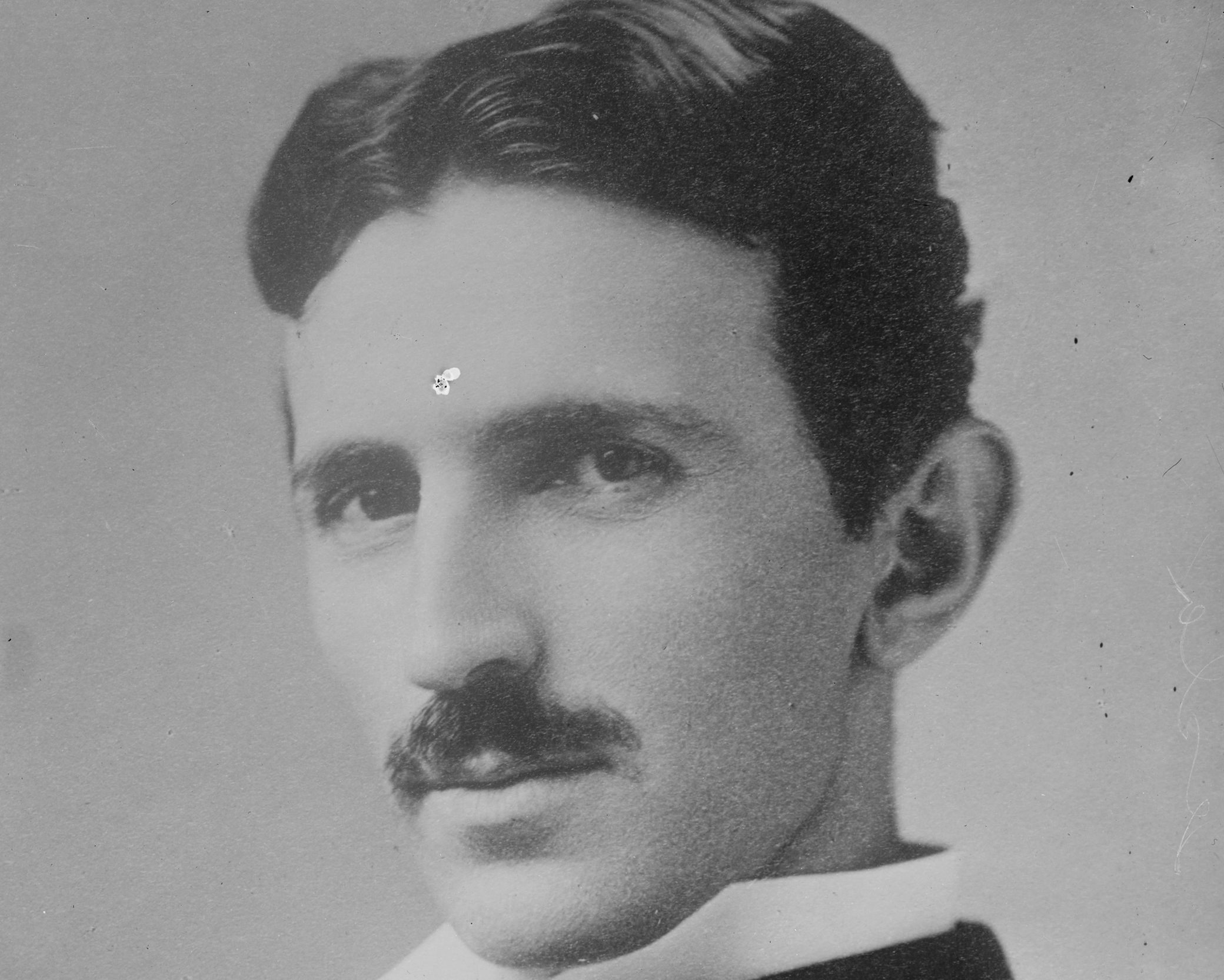

Nikola Tesla, c. 1890. Photograph by Napoleon Sarony. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Bain News Service photograph collection.

If any scientist watched by the FBI can lay claim to having a genuine mythology, it would be Nikola Tesla, whose impressive accomplishments in electrical engineering in his lifetime are only dwarfed by what he is believed to have done in the popular imagination. His voluminous FBI file—parts of which are still being released—can be broken down into two parts.

The first documents the Bureau’s growing frustration at having been unwittingly entwined in the numerous rumors surrounding what happened to Tesla’s papers and personal effects after his death; the second reveals their actual fate—as well as a bizarre coincidence almost too strange to be true.

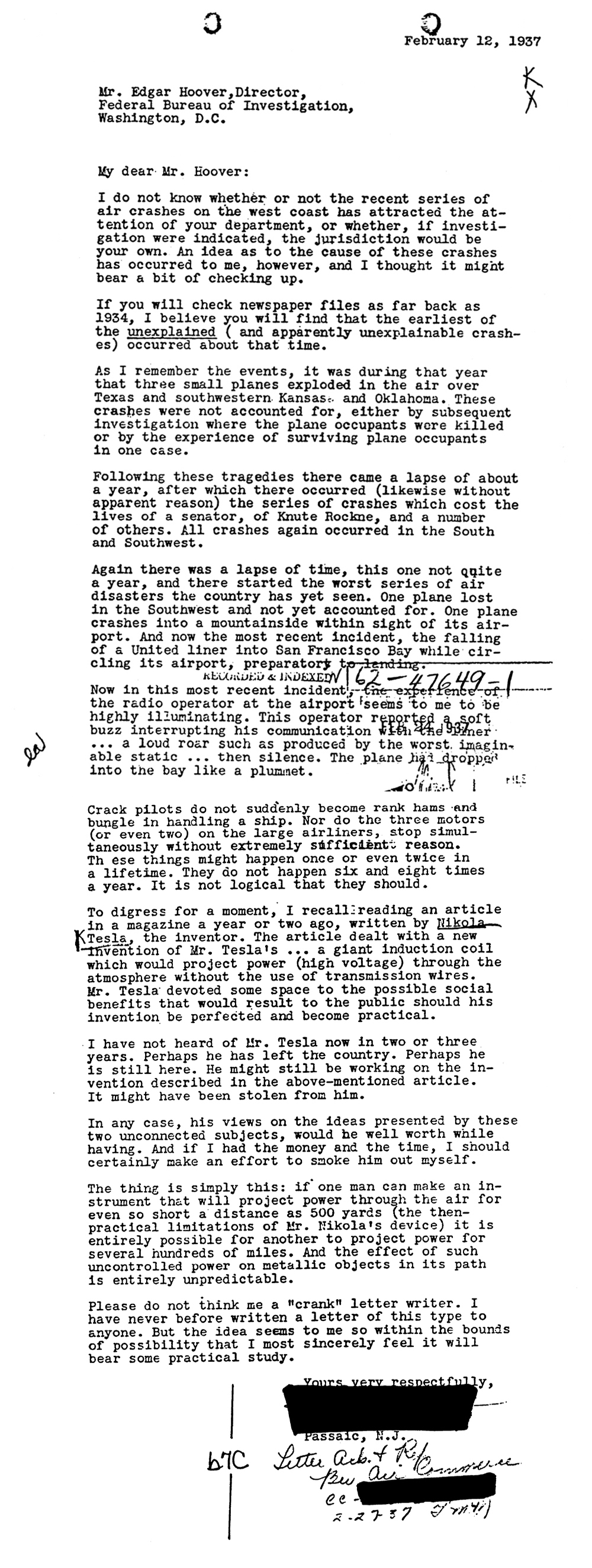

The file begins in September 1940, when FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was sent a New York Times interview with Tesla by a concerned citizen. Tesla had fallen on hard times in his old age and was trying to sell the military on the idea of his “teleforce device,” which was actually referred to in the article as a “Death Ray.” The tipster’s fear—echoed by a few others in the U.S. government—was that if these plans fell into the hands of the enemy, it could turn the tide of the then-ongoing world war.

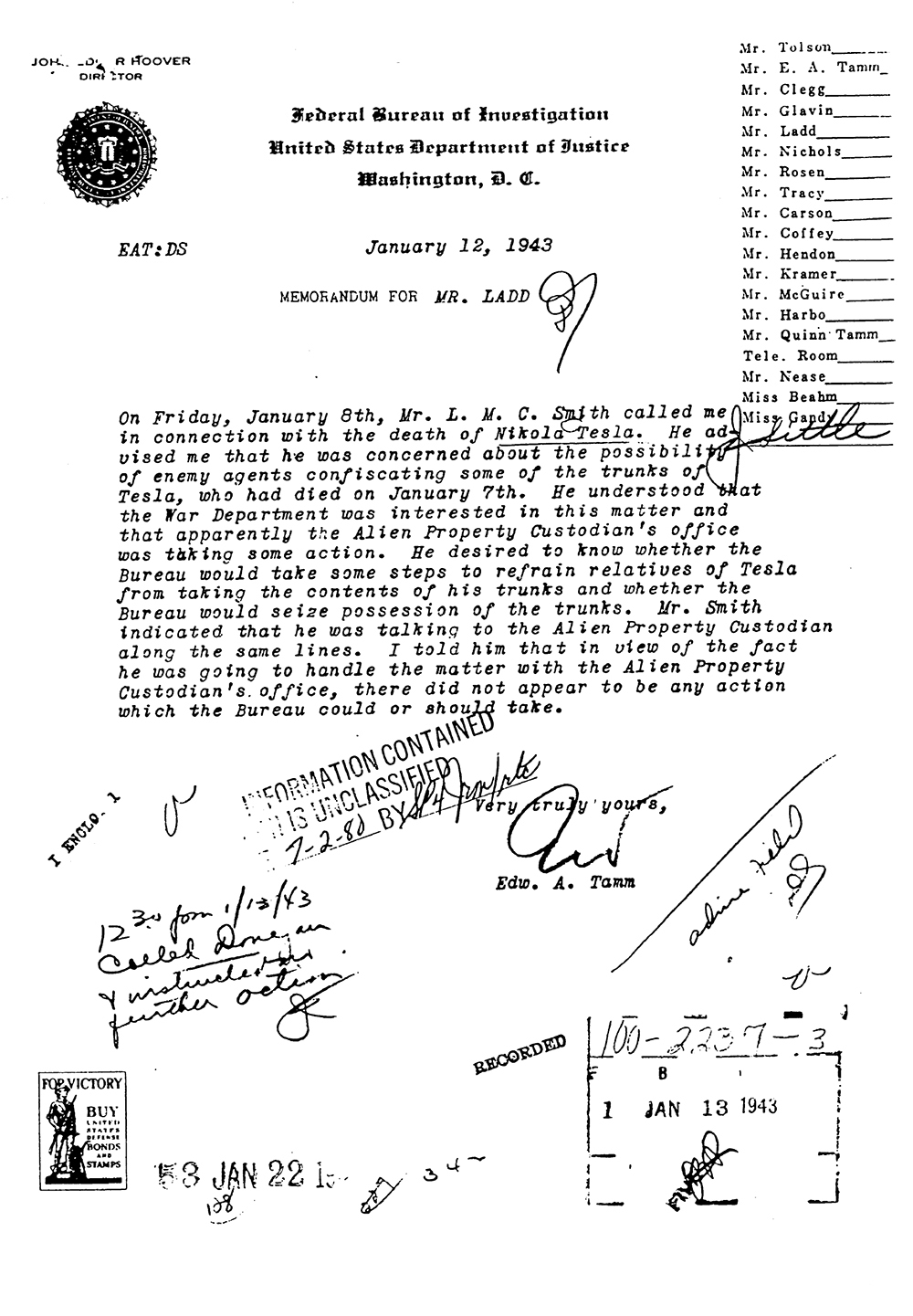

Hoover politely dismissed these concerns, as well as the ones that arose a few years later, when Tesla died and the Office of Alien Property Custodian (OAPC) took possession of any personal effects. Hoover likely thought the death-ray issue was closed until 1948, when he received the first of many letters asking for Tesla’s papers, claiming that the Bureau had taken possession of them as a matter of national security.

Hoover would continue to receive these letters for the rest of his life, and he would always respond that the writer was mistaken and that the papers were in possession of the OAPC.

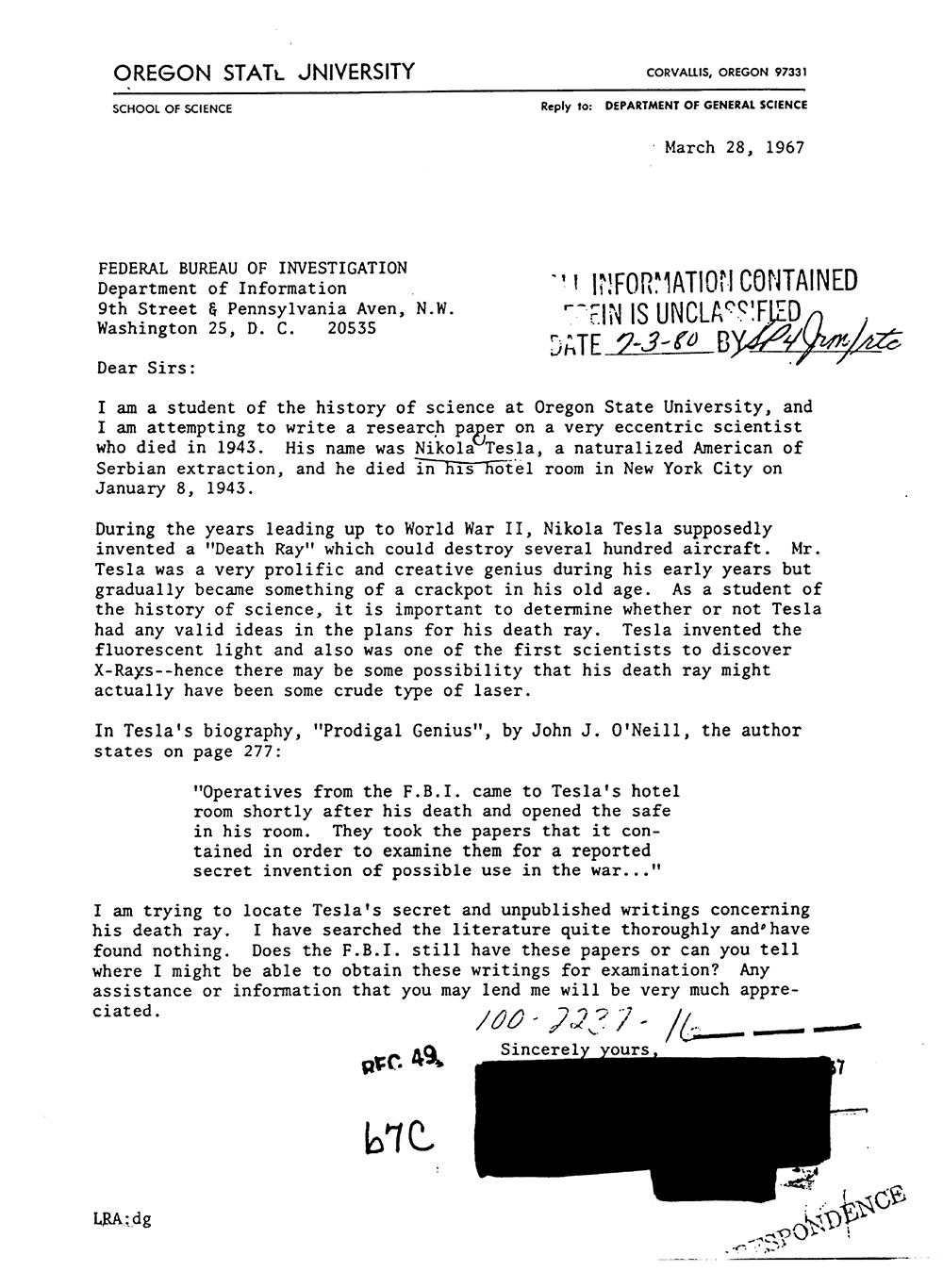

Eventually, in 1953, the FBI discovered the source of this claim: a 1944 biography Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla. Since the book had been out for nearly a decade at this point, Hoover decided against asking for a correction and just answered the letters as they came in over the next decades.

Heartbreakingly, one of the letters was from Tesla’s friend Kenneth M. Swezey, who explained that he had been in contact with OAPC, and they didn’t know where Tesla’s things were, either. This included Tesla’s Edison medal, which remains missing to this day.

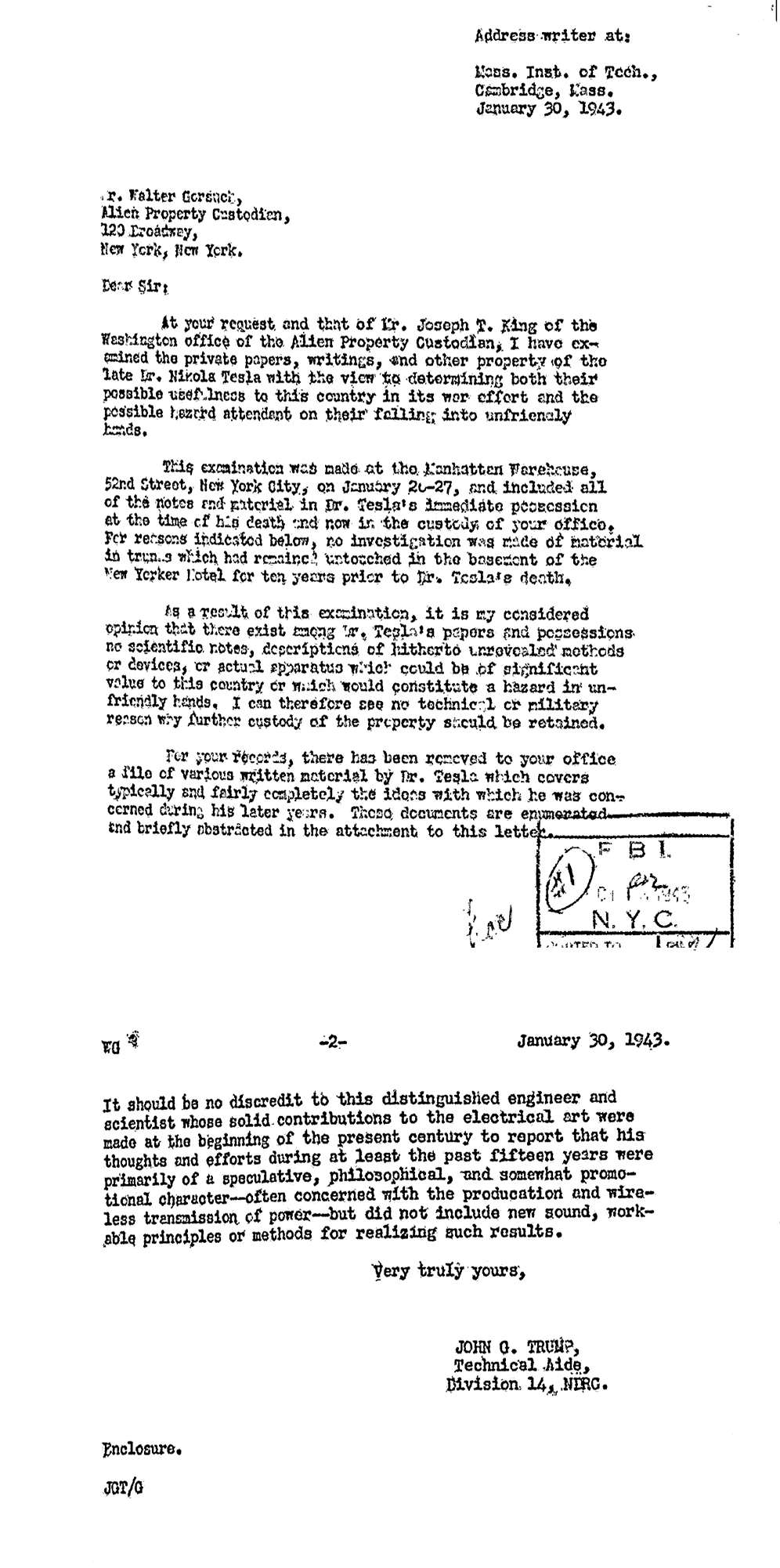

The second part of the file concerns the January 1943 analysis of Tesla’s papers by the OAPC, for which they sought the expertise of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology engineer. The engineer, who determined that the papers contained “nothing of significant value,” was named John G. Trump, a man also known as Donald Trump’s uncle.

Excerpted from Scientists Under Surveillance: The FBI Files, edited by JPat Brown, B.C.D. Lipton, and Michael Morisy. Published by The MIT Press. Copyright © 2019 MIT. All rights reserved.