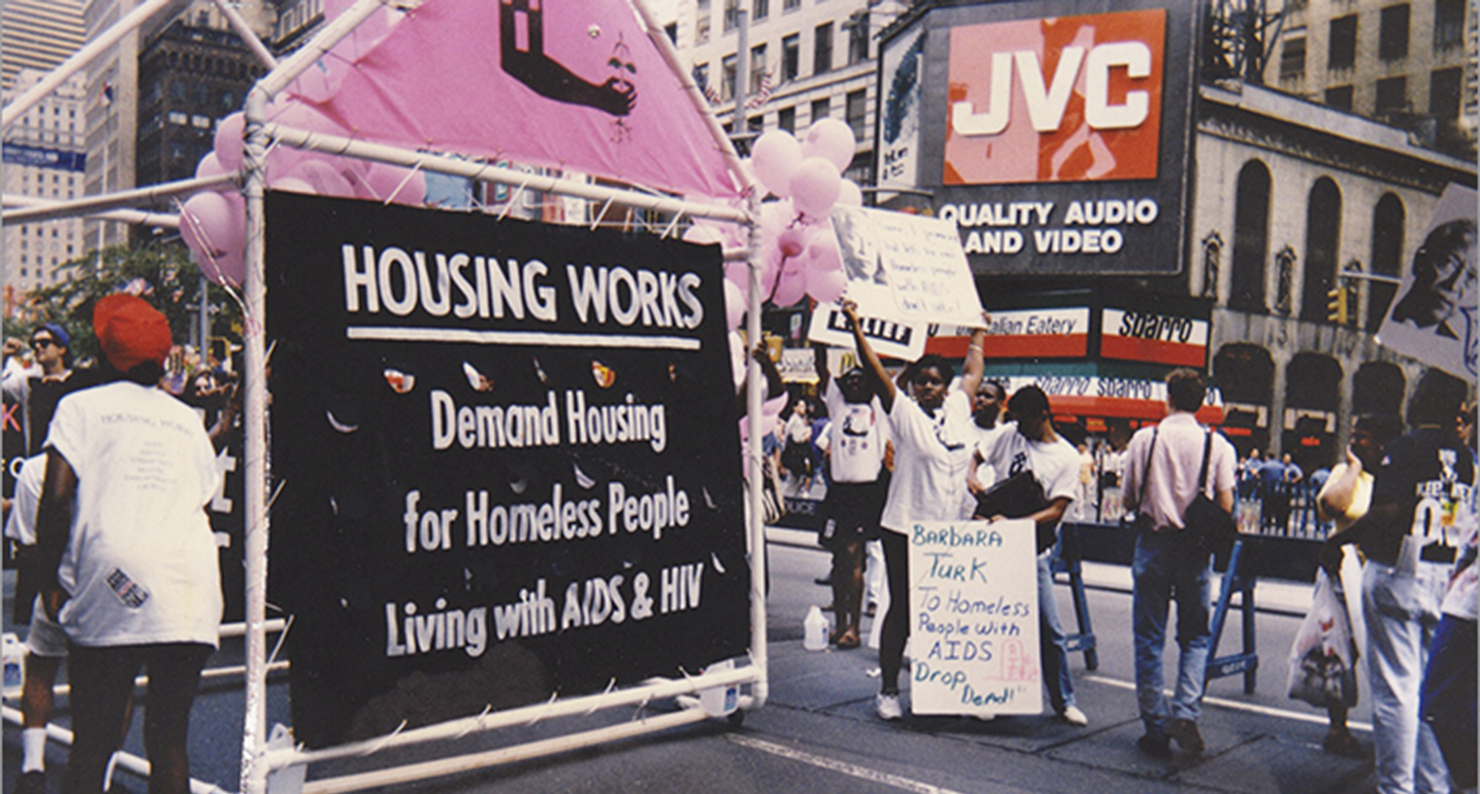

A home on wheels—Housing Works’ first Gay Pride float, June 30, 1991.

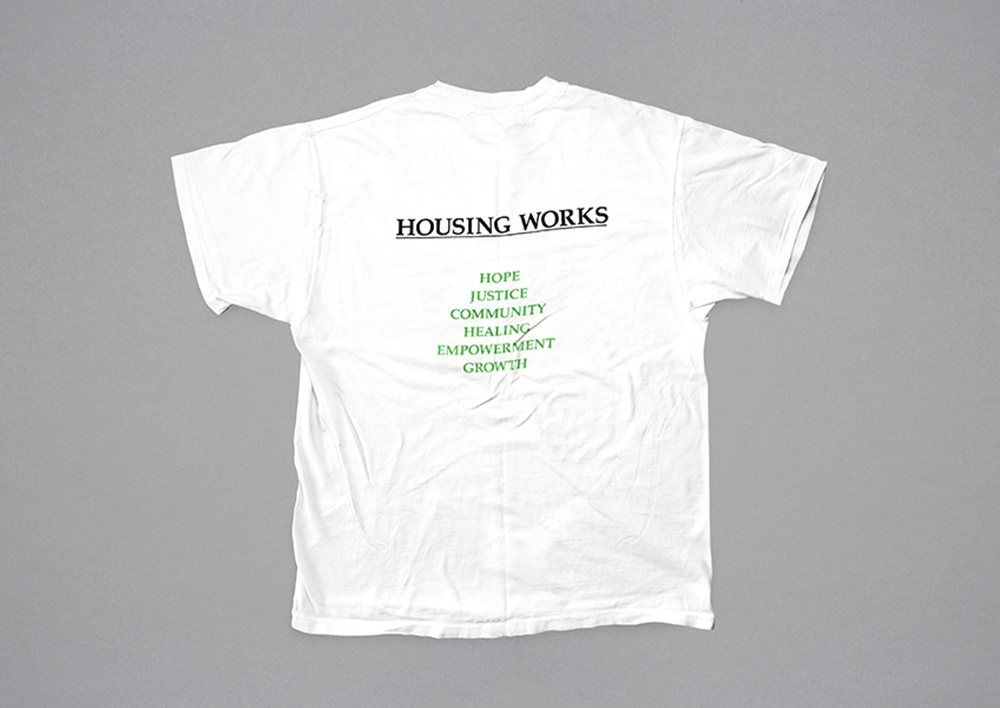

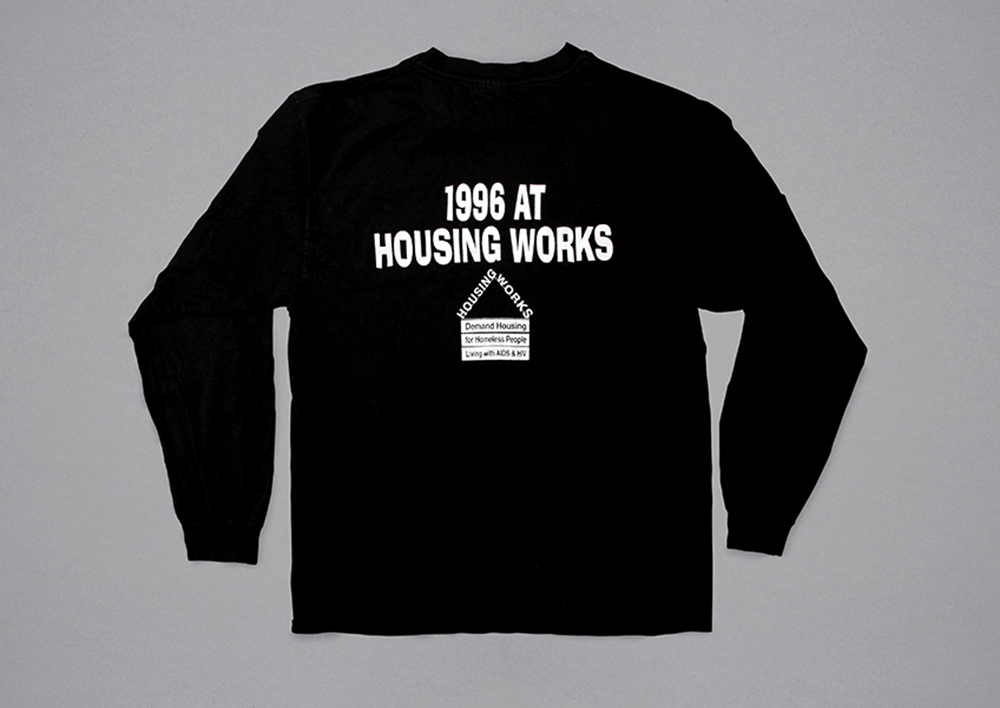

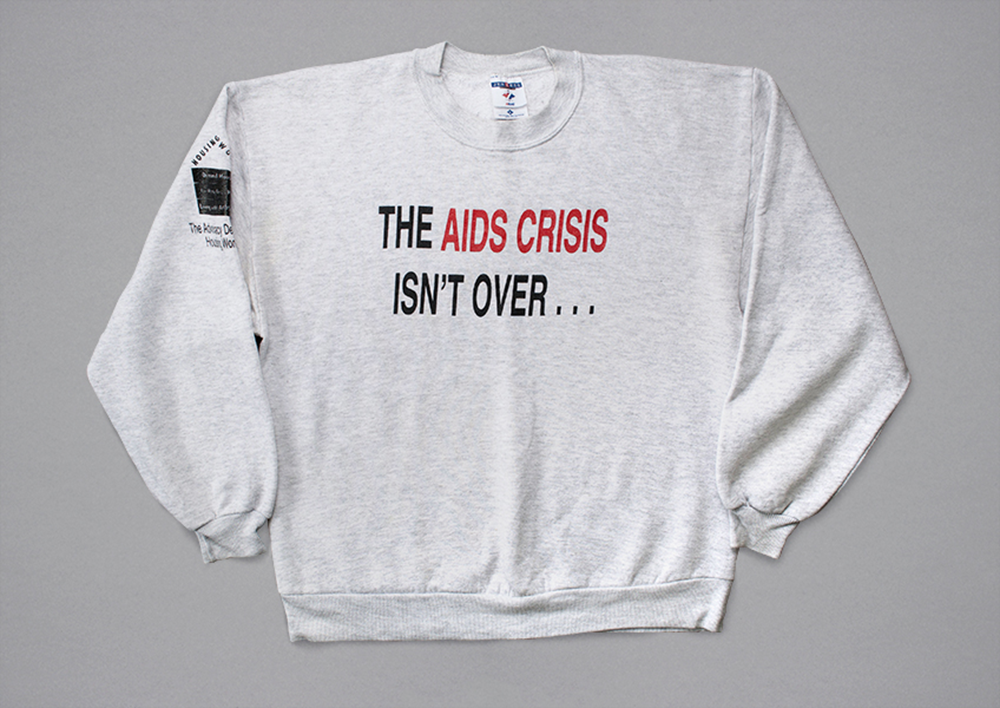

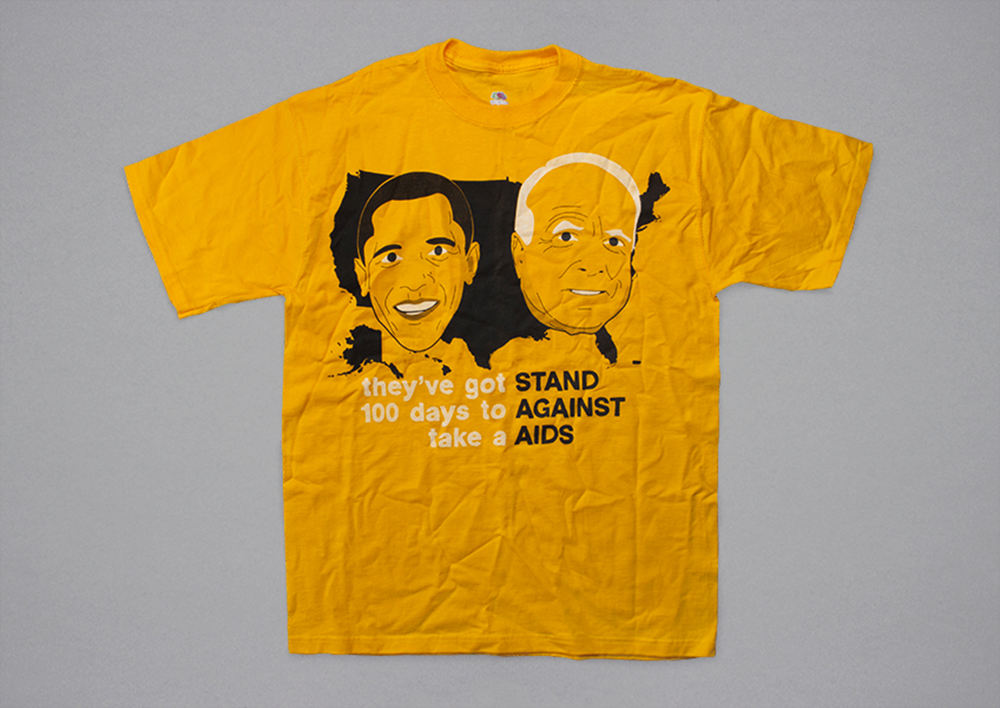

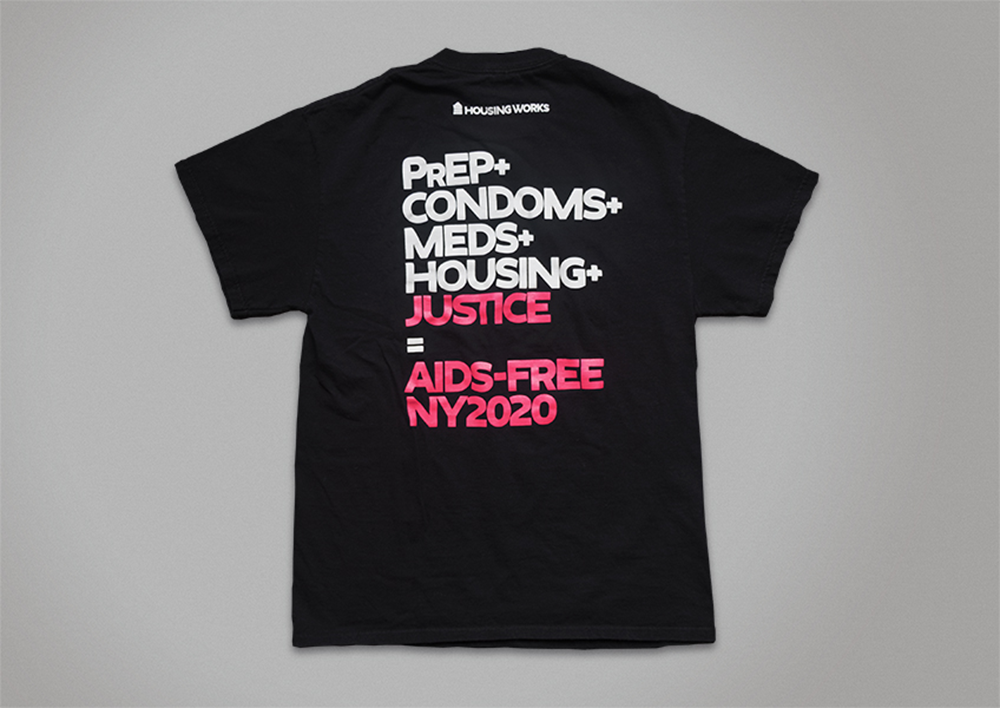

“Housing is health care. Connecting with other people is health care,” explained Lynn Walker, a managing director at Housing Works, a New York City nonprofit organization founded in 1990 that builds housing and supportive services for homeless New Yorkers living with HIV and AIDS. In order to explore the connections between health, housing, and design, I created a timeline of the organization, Housing Works History, that assembles architectural drawings; archival media, objects, photographs, and protest ephemera; key moments in housing policy; public health data; and present-day reflections by residents, architects, and advocates such as Walker. Below is a collection of T-shirts and personal effects worn by activists over the course of twenty-five years of speaking out.

In March 1987 the direct-action group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was founded at a meeting at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in Manhattan out of anger at government indifference to the AIDS epidemic.

At the start of the 1990s, New York City had less than 350 units of housing set aside for an estimated 13,000 homeless individuals living with HIV/AIDS. In response, four members of the ACT UP Housing Committee—Keith D. Cylar, Charles King, Eric Sawyer, and Virginia Shubert—founded Housing Works in 1990.

At the time, traditional shelters often required residents to be sober—a policy that effectively barred many people who were in need of housing. In contrast, Housing Works housing was “based on the premise that safe, stable housing is essential for homeless persons to gain control of their lives and necessary for them to be active participants in their own medical and psychosocial care,” Shubert and Mary Ellen Hombs later wrote in the Clearinghouse Review. The organization follows complementary “Housing First” and harm-reduction models to housing.

A “Housing First” policy prioritizes shelter. Once people are housed, they are then given access to a range of supportive services, such as job training, medical and mental health care, legal aid, and counseling.

Harm-reduction strategies minimize harm to individual and community health without requiring abstinence.

Located at 130 Crosby Street in Manhattan’s SoHo, the Intake Program, one of Housing Works’ first initiatives, encompassed a triage team, education and prevention programs, and referrals for new Housing Works clients to secure housing.

In 1987 the Centers for Disease Control defined the clinical diagnosis of AIDS as the presence of HIV alongside certain “indicator” diseases, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and lymphoma of the brain. Using contracts with the New York City Human Resource Administration (HRA) and HIV/AIDS Services Administration (HASA), Housing Works leased apartments in several buildings—as opposed to within one centralized building—and then sublet them to clients who met this diagnosis.

Many homeless individuals were living with HIV but not the “indicator” diseases that signaled AIDS in official eyes, however. Funneled into the shelter system, they were not eligible for HASA services. For them, Housing Works created the Independent Living Program, twenty-five apartments leased from private landlords. These clients held the leases in their own names while Housing Works provided case management, services, and assistance with utilities.

For both programs, the fledgling organization focused efforts on Manhattan’s Lower East Side—a neighborhood highly affected by the epidemic.

Housing Works favored a holistic approach, offering clients a range of services from dental, medical, and mental health care to addiction counseling, legal aid, and job training, as well as employment within the organization itself.

In 1992 architect Gary Deam designed pro bono the organization’s first thrift shop. Located at 136 West 18th Street in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, it provided both revenue and jobs for Housing Works clients who graduated from the organization’s Second Life Job Training Program.

Client Ivan Romero told the Housing Works publication Heart and Soul, “I got my GED, learned to budget my money, grocery shop, do laundry, and cook.” Throughout the 1990s, Housing Works transitioned hundreds of clients into staff through classes in maintenance and repair work, math, clerical skills, communications and self-esteem, harm reduction, computer technology, and English as a second language.

Between 1993 and 1995, Housing Works expanded its scattered-site housing program to Brooklyn and the Bronx; opened a needle exchange and a second thrift shop; established a prevocational job-training program in which clients learned to weave; acquired land and broke ground on its first capital project, located at the corner of East 9th Street and Avenue D in Manhattan’s East Village; and established links with Bellevue and St. Vincent’s Hospitals as part of their Tuberculosis Scattered-Site Housing Program, twenty-five apartments in buildings across the city designated for homeless patients living with HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis to move into after being discharged.

Not everyone was welcoming. The organization faced NIMBYism in SoHo and the Lower East Side after it proposed a health-care center at the corner of Grand and Greene Streets and a housing development at 186-194 East 7th Street in 1993. “In both neighborhoods, opponents are spreading scare stories about TB epidemics, declining property values, increased drug abuse, and crime,” reported the newsletter Neighborhood News. The projects ultimately were quashed by state representatives Martin Connor, Steven Sanders, and Sheldon Silver and city council member Antonio Pagán.

Architect Benjamin Kracauer designed pro bono Housing Works’ popular bookstore cafe at 128 Crosby Street in SoHo, which opened in 1996. The organization had predicted in the fall/winter 1995 issue of its newsletter The Key that the store would be a “complete vindication from those naysayers who fear that service programs like those operated by Housing Works would have a negative impact on the presence of the neighborhood.” It has since become one of New York City’s most beloved literary hubs.

Kracauer also designed a health-care center at 320 West 13th Street that opened in 1996.

“I’ve lived in eighteen different places, and they all reminded me of jail,” said a resident of 743-749 East 9th Street to New York Times reporter Julie V. Iovine in April 1997. “Here, it feels like life, not death.”

Housing Works’ 19,000-square-foot East 9th Street facility, designed by Alan Wanzenberg, opened in 1997. With thirty-six studio apartments for single adults living with HIV/AIDS, it also housed a cafeteria, a garden, a roof terrace, a gym, a day-treatment center, and The Works, a commercial catering company that trains and hires clients to cater events.

On the heels of this success, the New York City Human Resources Administration under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani withdrew $6.5 million worth of New York City government contracts, citing financial improprieties and failure to keep accurate records. The move jeopardized housing for 220 clients in 181 scattered-site apartments.

In 1998 Housing Works opened its second ground-up facility, a 33,000-square-foot building at 2640 Pitkin Avenue in the East New York section of Brooklyn. The building includes thirty-two units for single adults living with HIV/AIDS, a cafeteria, and a garden and offers on-site medical care and counseling. It was designed by the Pratt Planning & Architectural Collaborative, a team of students and faculty from Pratt Institute that included Joan Byron, Lynn Gernert, and Robert Zagaroli.

That year Housing Works also filed a lawsuit in New York Supreme Court in Manhattan claiming that the city’s withdrawal of funds was done out of retaliation “for years of furious protests, mocking placards, and critical news releases” in response to Giuliani’s policies on HIV and AIDS.

In 1999 U.S. District Judge Allen G. Schwartz ruled that city officials had acted out of “retaliatory intent” against Housing Works. In his opinion, he noted “a clear showing of a pattern of antagonism by the Giuliani administration towards plaintiff.”

In 2002 the organization faced NIMBYism yet again, this time in Harlem: when plans were announced to redevelop three abandoned nineteenth-century brownstones on West 130th Street into supportive housing, politicians and residents filed an unsuccessful petition with the Supreme Court of the State of New York to block the plan.

In 2003 Housing Works founded the Women’s Transitional Housing Program in Brooklyn, scattered-site housing for single women released from prison within the past twenty-four hours.

Founded in 2004, Housing Works’ Transgender Transitional Housing Program provides newly furnished scattered-site apartments where transgender and gender-nonconforming homeless individuals with HIV and AIDS may live for up to two years.

Once housed, clients enjoy the autonomy stability brings: they “can put their meds in the bathroom, just like other people do. And they can have a clock, just like other people do, and watch the clock and take their meds on time,” explained Lynn Walker, who pointed out that housing “contributes materially to their health care.”

Housing Works cofounder Keith D. Cylar was “everything the world dismisses—dyslexic, queer, black, and HIV positive for more than twenty years. But he was too powerful to dismiss: an entrepreneur, a respected researcher, a member of numerous boards, including the National Harm Reduction Coalition, and a talented clinician who helped house more than 15,000 HIV positive New Yorkers,” wrote Nina Herzog in an obituary that ran in POZ in July 2004.

In the mid-2000s, Housing Works led caravans of activists to Washington, DC; opened family housing in East New York; inaugurated a scattered-site housing program in Staten Island; and received a $4.8 million settlement from the City of New York.

“I’m not sure people appreciate how much the Giuliani administration attempted to silence dissenting voices, in particular in communities that relied on city funds to service needy people,” Charles King told Jim Dwyer of the New York Times in May 2005. “I think Housing Works was used as an example to let other organizations know what would happen to them if they advocated on behalf of their clients.”

The Harlem buildings opened in 2008. The 3,000-square-foot brownstone at 162 West 130th Street has two two-bedroom and two three-bedroom units for families with at least one parent living with HIV/AIDS, while the 6,800-square-foot combined brownstone at 143-145 West 130th Street includes eleven units for single adults living with HIV/AIDS, a common area, and a backyard. “We have our community brunch on Sundays, when everybody gets together. The backyard we love, because we have cookouts…When you want to be alone, you have your apartment,” resident Desi Glazier said, adding that the building “really saved my life.” Both were designed by Archimuse.

The Women’s Transitional Housing Program found a permanent home in 2009. The 6,720-square-foot townhouse at 454 Lexington Avenue in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn houses twenty units. “When a woman walks into this building, the first thing they say is, ‘Wow, this place is so clean, and everyone is so nice,’” said coordinator Annette Lacoot-Hylton. The housing also gives them access to crucial health care that helps them manage their HIV status, and Lacoot-Hylton explained that within thirty to sixty days of their stay, the virus becomes undetectable: “They are virally suppressed.”

Within one week of the magnitude-7.0 earthquake that devastated Haiti in January 2010, Housing Works sent staff, physicians, and $30,000 worth of medical and relief supplies to Port-au-Prince. Working with local groups, the organization subsequently opened clinics and studied the long-term and interrelated complications of disaster relief, poverty, and HIV/AIDS.

In New York in the years 2010–15, Housing Works opened new multifamily housing in the Bronx and Brooklyn; used $541,000 in federal funds from the Affordable Care Act to expand the East New York Community Health Center; and established the Asylum Program, housing for LGBTQ and HIV/AIDS activists from African and Caribbean countries.

By the end of 2016, Housing Works had established properties and programs in all five boroughs; had planned new residential programs for homeless LGBTQ youth and asylum seekers; was running twelve thrift shops with an annual revenue of $16.1 million; and had helped to create the 2015 blueprint to end the epidemic in New York State by 2020, which offers recommendations for decreasing new HIV infections to fewer than 750 annually within five years.

Explore Home, the Winter 2017 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.