Opium box, c. 1821. Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mrs. Anna Mantel Fishbein.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Lucy Inglis, author of Milk of Paradise: A History of Opium, now available from Pegasus Books.

There are many great accounts of opium, and some of the most well-known, such as those of Thomas De Quincey or Samuel Taylor Coleridge, are lauded for their depictions of addiction. Yet addiction is only a small part of the much larger history of opiates and often clouds perception of the greater good the poppy can do. Mankind’s affinity for opium and its derivatives has been recognized for millennia, seen in every aspect of early cultures, from some of the earliest coinage, minted around 330 bc in Şuhut in what is now eastern Turkey, to works of art such as the Minoan Poppy Goddess of ancient Crete.

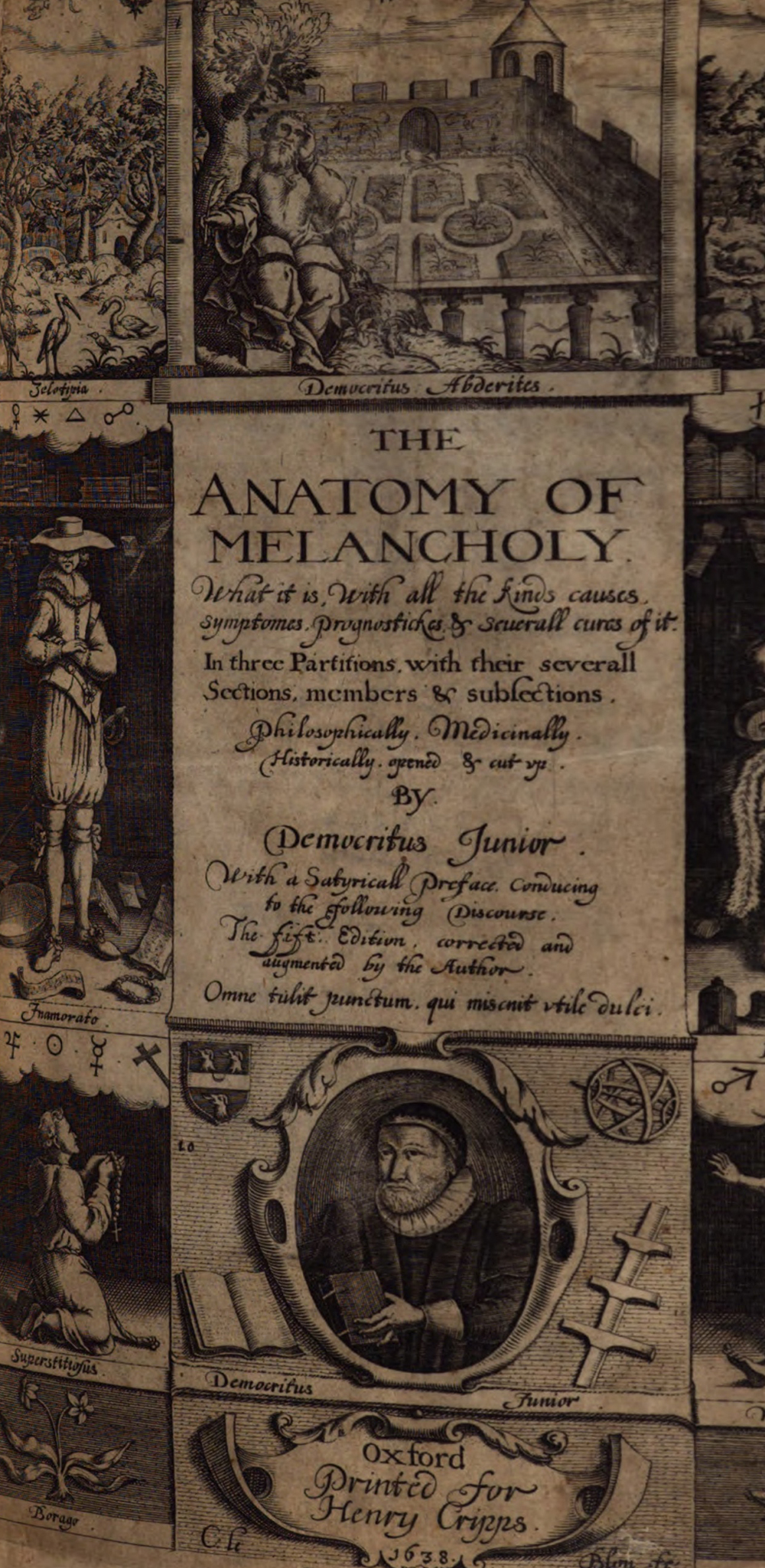

Yet it took until the early modern period for writers to begin to record their own relationships with the drug and bring it into a wider context, in terms of mental as well as physical health. One of the first to do so was Robert Burton (1577–1640). He was an Oxford scholar who wrote the first work to directly address problems with mental health in 1621. The Anatomy of Melancholy: What It Is, with All the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of It is particularly touching on the “continuall cares, fears, sorrows” of insomnia, for which he recommended opium, as well as mandrake, henbane, and hempseed.

A speedy cure for insomnia, he insists, is essential, as sleep is “sometimes is a sufficient remedy of itself, without any other Physick.” The direct link between mental health, mental distress, and opiate use is implicit in Burton’s work. Samuel Johnson, a man who struggled throughout his life with depression and alcoholism, was no stranger to laudanum either, and said The Anatomy of Melancholy “was the only book that ever took him out of bed two hours sooner than he wished to rise.” We can only hope that it was after a good night’s sleep.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Chris Cander, author of The Weight of a Piano

• Preston Lauterbach, author of Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers

• Rosellen Brown, author of The Lake on Fire

• Patricia Miller, author of Bringing Down the Colonel

• Monica Muñoz Martinez, author of The Injustice Never Leaves You

• John Wray, author of Godsend

• Imani Perry, author of Looking for Lorraine

• Ken Krimstein, author of The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth

• Scott W. Stern, author of The Trials of Nina McCall

• Katherine Benton-Cohen, historical adviser for the film Bisbee ’17

• Victoria Johnson, author of American Eden

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Linda Gordon, author of The Second Coming of the KKK

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing