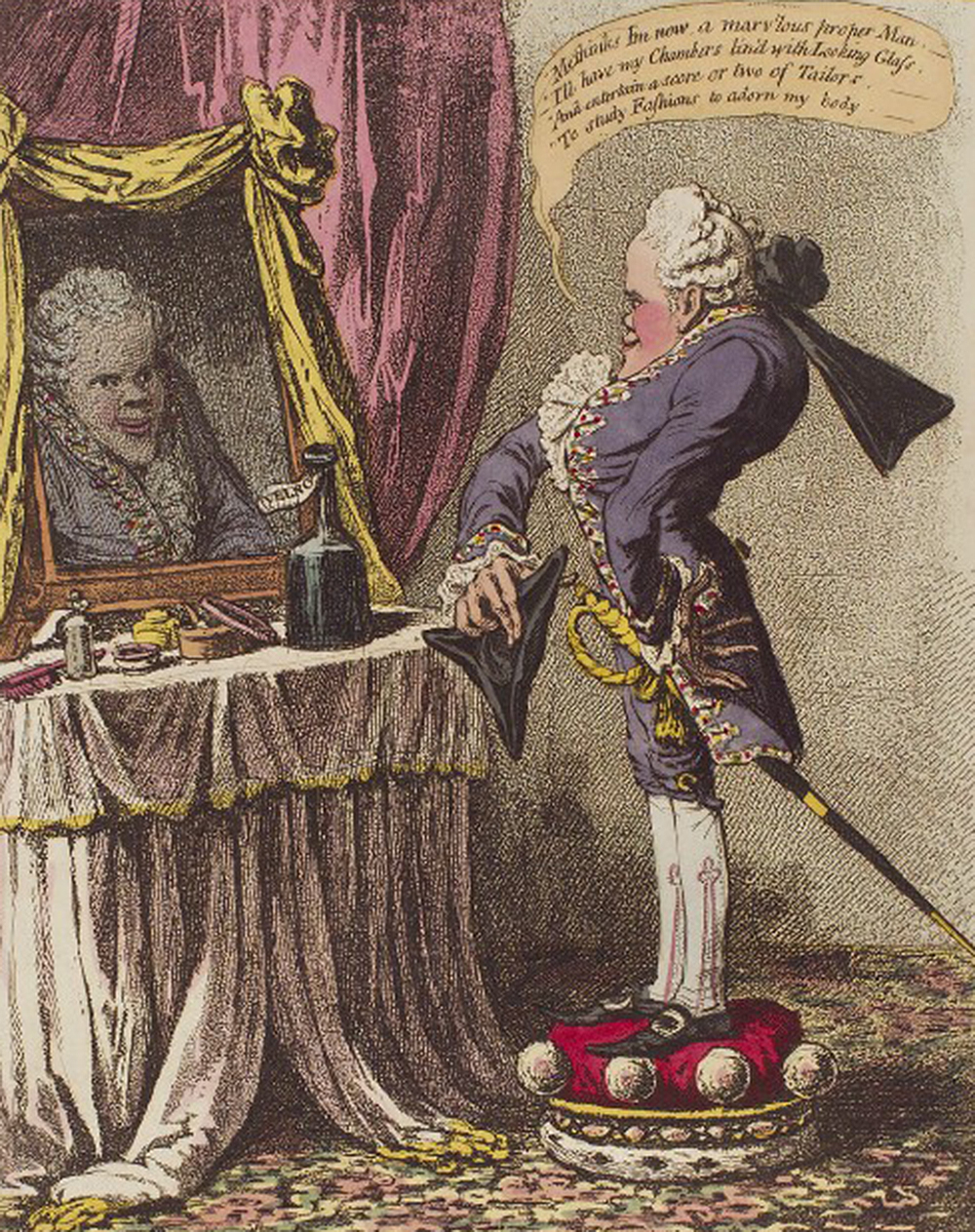

Frontispiece to The Progress of a Rake: or, the Templar's Exit, 1732. The British Museum, Prints and Drawings.

The good thing about venereal disease is that it isn’t serious—or at least, it certainly didn’t seem so to a good many eighteenth-century writers and artists. In Tobias Smollett’s Roderick Random (1748), the enterprising young hero casually contracts, and just as casually cures, an infection that he caught somewhere “in the course of an amour.” In Edward Kimber’s novel The Life and Adventures of Joe Thompson (1783), the protagonist laughingly recalls the gullible friend who “got into a tête-à-tête discourse with a coronet” at a masquerade, only to discover the following day that his conquest was actually “a woman of the town,” who had not only prompted him to spend a great deal of money, but also—and this is the punchline—given him “the French Disease.” And in his salacious tell-all autobiography, the “profest Rake and Whoremaster” Gilbert Langley recalls with amusement how he and his comrade, enjoying a period of unrestrained debauchery, “had almost drain’d our Pockets...and got the French Disease.” Whether Langley and his friend had “almost” contracted the infection or definitely caught it is immaterial: certainly it doesn’t prevent either man from forming designs on a beautiful young woman to whom Langley—with no further mention of the disease—soon after proposes marriage.

Admittedly, such representations emerged from a culture in which venereal disease was widely believed to be curable, or at least treatable: as the notoriously debauched Earl of Rochester put it, even the most extravagant use of prostitutes could raise no concern when “the worst you can fear is but a disease, / And diseases, you know, will admit of a cure.” Yet diaries, letters, and other historical records are full of references to debilitating and disfiguring symptoms—and even Rochester’s poetic boasts take on a grim irony given his own death from the most horrific complications of tertiary syphilis at the age of thirty-three. How could so many writers and artists have depicted venereal disease as unserious—not just dismissing it as untroubling, but deliberately invoking it as an object of amusement or celebration—when young men like Rochester were clearly dying from it?

Many historians have argued that there was a more relaxed attitude towards sexuality in the aftermath of the Restoration, but no enthusiasm for libertinage can quite account for the radical split in this period between the brutal physiological realities of venereal disease and its insouciant, even cheerful, treatment in art and literature. While Restoration and eighteenth-century culture undoubtedly supported a wide range of different attitudes towards the disease at different moments and among different groups, the many dismissive and celebratory accounts of venereal infection clearly had something other than strict medical accuracy in mind. They were informed less by the grisly details of living with an infection than by broader questions about who or what that infection might signify.

The “maleness” of venereal disease in the eighteenth-century imagination coalesced around two particular groups: officers—a term that I am using very broadly here, to denote military or naval personnel of all ranks—and gentlemen, my umbrella term for men of leisure, with or without a title. There was some rationale for this association in that both groups were believed to be inherently prone to promiscuity: titled lords and leisured gentlemen had the time and money to pursue sexual conquests and to support multiple mistresses and prostitutes; military men were believed to suffer under their removal from the stabilizing influence of domestic life, and to seek comfort in the transient pleasures of the whorehouse. Both groups were also traditionally representative of male power, with the gentleman possessing social, financial, or political clout, and the officer embodying manly ideals of physical strength and military skill. Accordingly, in connecting officers and gentlemen with venereal infection, writers and artists also strengthened an imaginative association between the disease and male power—and some works even represented the infection as a badge of sexual or social prowess.

For the elegant man of fashion, venereal disease was all the rage: according to some Restoration and eighteenth-century commentators, the infection circulated among the beau monde like a hot new commodity, signaling a lifestyle of pleasure and luxury. Some even referred to it as the “modish” or “fashionable distemper.” While remarks on the fashionableness of elite male infection almost certainly belied the prevalence of venereal disease among poorer men, it was as much the amused tone of such comments as their assumptions about the exclusive nature of infection that jarred with reality. Even a “moral drama” like Bickerstaff’s Unburied Dead (1743) played the venereal disease vogue for laughs: in the play’s opening scene, a group of undertakers laments the increasing incidence of infection—not because it is killing off the population, but because it is damaging a brisk side business in cadavers for medical dissection: “This fashionable Distemper is a great Loss to us,” complains the undertaker Quicandead; “we can seldom get a Body sound enough for the Surgeons; they object, Rotten Bones will never make good Skeletons.”

The association of venereal disease with Frenchness seemed further to cement its imaginative attribution to men of fashion, with writers comparing the alleged enthusiasm for “French pox” with the rage for other Gallic imports. In a satire on Restoration courtiers Samuel Butler joked that healthy men might even pretend to have the disease just to appear de rigueur:

By sudden Starts, and Shrugs, and Groans

They Pretend to Aches in their Bones,

To Scabs and Botches, and lay Trains

To prove their Running of the Reins;

And, lest they should seem destitute

Of any Mange, that’s in Repute,

And be behind hand with the Mode

Will swear to Chrystallin and Node.

Here, as in many other denouncements of the “fashionable distemper,” it is the Francophile aristocracy who seem to constitute the satirist's primary target. No wonder, then, that one satirist contended “People of Quality” preferred a French servant to an English one; after all, a Parisian fellow was far more likely to be able to “assist his Lord in the Cure of a fashionable distemper” than a “dull, plodding English Booby.”

Both the disease’s alleged continental origins and its association with youthful male virility made it a common feature in stories of the Grand Tour, and an ill-timed infection provided comic relief in many an upper-class male coming-of-age narrative. Indeed, among the many casual references to venereal disease in Restoration and eighteenth-century literature are anecdotes attesting to the amusing predictability of such infections among “young Gentlemen, during their Minority, and before they arrive to Years of Maturity”: in this context, venereal disease seems to be much like cystic acne, wet dreams, or any other of the cringeworthy but fundamentally untroubling conditions that characterize male adolescence.

For writers who wished to champion a leisured male lifestyle, the association of venereal disease with upper-class masculinity could also offer a surprisingly productive means of defending elite male prerogatives. In a remarkable number of Restoration comedies—William Wycherley’s The Country Wife (1675), Thomas D’Urfey’s The Fond Husband (1677), Aphra Behn’s The City Heiress (1682), John Crowne’s City Politiques (1683), and Colley Cibber’s Love’s Last Shift (1696), among others—male infections correlate with elevated social status, and often (seemingly paradoxically) with sexual or physical prowess as well. In Behn’s play, for example, the hero’s pox poses no impediment to his pursuit of the heiress of the title; if anything, Tom Wilding’s infection adds to his desirability as a lover, by sharpening the contrast between his own sexual confidence and the anxious ambition displayed by his uncle and rival, Sir Timothy Treat-all.

Other texts and images connected sexual infections with military and naval officers. Within this demographic, too, venereal disease was identified as a routine feature of adulthood, with surgeons dispatched to the field or ship expecting to deal with the casualties of sex as well as of war: indeed, the satirist Ned Ward wryly remarked that, aboard a naval vessel, “one Pocky Whore brings the Surgeon more Grist in than a thousand French Cannon.” Many medical texts reinforced the association by presenting officers as case studies, and some specifically remarked on the relaxed attitude to infection among the troops. To use the tactful phrase employed by army physician Donald Munro, military men were apparently “not shy in owning Complaints of that Kind.”

Condoms were not only routinely represented using military language and closely associated with military personnel; they were also rumored to have been invented by a colonel in the British army. One comic encomium on the “device,” a 1744 mock-epic entitled The Machine, or Love’s Preservative, uses the association of officers with venereal infection in order to commend condoms as a vital instrument in preserving national security. Identifying venereal disease as a threat to all British men, the poem lauds the prophylactic’s alleged creator, “Colonel Cundum,” as a hero whose invention has come to play a vital role in guarding “Albion’s Safety.”

Although the speaker of The Machine does observe that a “willing Maid” might use a condom in order to avoid an unplanned pregnancy, the poem as a whole classifies condoms as items primarily of service to men—and primarily of use in preventing venereal disease:

Happy the Man, in whose close Pocket’s found,

Whether with Green or Scarlet Ribbon bound,

A well made Cundum; he nor dreads the Ills

Of Cordees, Shanker, Boluses, or Pills;

But arm’d thus boldly wages am’rous Fight

With Transport-feigning Whore, in Danger’s Spight.

Here, as in many other works of the period, sex is presumed to involve a male and a female partner, but only the male partner seems to require a prophylactic to prevent infection—and once again, the language of military conflict is used to celebrate libertinage: the speaker compares the courage of the condom-wearing lover to that of “Great Ajax…the Grecian Chief” who, “prepar’d / With seven-fold Shield, the Trojan Fury dar’d.” By contrast, the “hot Youth” who neglects to place a “sheathing Scabbard on his Metal Blade” is stricken with sores, “Heat of Urine” and penile discharge—all the “Sad Symptoms of a Thousand Woes his Due, / For Vent’ring all unarm’d to th’hostile Field, / And slighting Safety in Minerva’s Shield.”

The same privileging of male prerogative colors The Machine’s comparison of commercial sex with warfare, as the speaker’s martial vocabulary at times implicates prostitutes as the “enemy”: one “Wench unchast” is described as having a “polluted Touch”; another “foul Fair-One” is described as living in filthy rooms; a third, soliciting men on the streets, is described as a “Nymph insidious.” Yet these epithets, while they malign “polluted” prostitutes, never extend into a condemnation of either prostitutes in general or the system of prostitution at large: quite the contrary, the poem’s opening lines commend the nation’s “Whores thrice magnificent,” celebrating not only those who pleasure kings and employ the “wanton Hours of Garter’d Lords,” but also those who “strole in meaner Plight” at Temple Bar and in Drury Lane. Like the condom, the robust prostitute is identified as a point of national pride, and the poet’s exhortations to use condoms appear to be aimed as much at preserving Britain’s tradition of transactional sex as at safeguarding the health and security of the nation’s menfolk.

Indeed, the poem concludes with a call to arms, as the speaker not only invites his male reader to go forth and “swive each Night” with the protection of a condom, but specifically suggests that he satisfy his “best” desires with an “Exstatic Harlot.” Condemning “queer” and “filthy” practices like “flogging,” “Huffling, Gigging, Semigigging, Larking,” and “Barking,” the speaker insists: “Rather than deal in such unnatural Ways / I’d risk the Pox and naked swive Nan Hayes.” This concluding pronouncement, with its imagined choice between unprotected heterosexual vaginal sex and allegedly “safer” alternative practices, at the same time that it confirms the text’s privileging of heterosexual male desire, also undermines the emphasis on sexual safety, by reinforcing the connection between venereal infection and masculine prowess. The template for “good” sex involves a virile male consumer and a compliant prostitute—and even risky commercial sex is apparently preferable to emasculating practices like masturbation, flogging, or fellatio. Paradoxically, then, despite its best efforts to promote the condom as a manly accessory, The Machine ultimately reinforces a conception of male sexuality that favors risky pre- or extramarital adventure over the safety of sex within marriage. If nothing else, the poem’s speaker suggests, at least a bad case of the pox will prove you’re not a masturbator.

Adapted from Itch, Clap, Pox: Venereal Disease in the Eighteenth-Century Imagination, by Noelle Gallagher, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2018 Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.