Mrs. Tinkham, c. 1875. Photograph by William H. Mumler. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

The dead spoke through Leonora Piper, and the living answered through her hand. Shouted, really, because the connection between her hand and Eternity was often spotty. Calling on the dead required this kind of stagecraft in the waning days of the Spiritualist movement, when every quack with a set of candles claimed knowledge of the occult.

Leonora would first enter into a trance, goosefleshed and murmuring. The sitters would take her hand. They would then scream questions at her open palm, as though it were a murder suspect, or a bad dog, or the receiver of an old-timey telephone. In fact Leonora called her hand “my spiritual telephone.” Perhaps she knew, psychically, that her séances would one day resemble something far more terrifying: bad improv comedy.

Alice James did find it hilarious. Her brother William—a professor at Harvard, one of America’s most important philosophers and psychologists, and the brother of its most famous living novelist, Henry James—had been fooled by a Boston housewife who claimed to speak to dead people. By the time the eldest James sibling wrote to Alice in 1885 requesting a lock of hair (to test Leonora’s “psychometric” abilities), he had already sat for multiple sessions in the psychic’s darkened parlor, scribbling notes as she stuttered out communiqués from the spirit world. Leonora had distinguished herself from pretenders with the maternal exactness of her insights. She knew things about the dead that mothers know—the hue of a birthmark, the shape of a scar. It helped that she was a mother herself and looked the part, with her high-necked dresses and fussily wreathed hair.

The twenty-eight-year-old Leonora never advertised her abilities. If anything, she seemed embarrassed by them. But word had gotten around the previous year, when she had visited a clairvoyant, a blind former judge, to ask about a pain in her side and passed out at his table. When she came to, she hastily scribbled a note: a message for your honor, she explained, from his dead son. Leonora had not intended to upstage a stooped provincial psychic in his own home. Back then, she wanted only to have more babies and live out her tidy little life. As she got older, she refused to travel for any psychic business unless her kids could come, too. But she lived in a war-ravaged country of worn-out people, all broken from burying children and pledged to private ghosts. They pleaded for her help. Who was she to refuse them?

So she offered her mediumship to those in need: the grief-stricken, the spiritually tortured, the philosophically curious. William, mourning his own loss, was all three. He was also the chair for the Society of Psychical Research, a consortium of scientists convened to investigate the paranormal. The work had made him cynical. There were so many frauds and fakes like Madame Blavatsky and Eusapia Palladino, costumed phonies dimming the lights and shaking tables. In numerous hand-wringing letters, his less credulous colleagues worried for his reputation, if not his sanity. Leonora, he guessed, would bring more of the same. But, not long into their acquaintance, she began to trace the outlines of a word: a blurred string of syllables that resolved, upon repetition, into Herman. Herman was the name of William’s dead infant son.

He knew this jolt to the heart proved nothing—the name of his dead baby wasn’t exactly secret knowledge. But subsequent years of sitting across from Leonora led him to believe that she was, in his words, a “white crow”: the rare real thing, and a kind of miracle.

William was a lapsed artist, a heretical scientist, and a believer without a creed. If he believed in anything, it was in the power of belief itself: the way it could offer solace, shelter, and transform a person. Our beliefs, he thought, are shaped not by the exercise of reason but in “the dirt of private fact.” They work upon us as intimately as a child’s name, as a hand held in the dark. They are not—can never be—a foothold into certainty. But they can offer us a ladder out of despair.

One night in his mid-twenties, drowsy from reading, William James had a vision. Before him appeared a young epileptic man with “greenish skin, entirely idiotic,” sitting still as a “sculptured Egyptian cat,” moving nothing but “his black eyes and looking absolutely nonhuman.” That shape am I, thought William.

The epileptic man, William knew, was a “vastation”: his father’s term for depressive episodes of sinister, hallucinatory intensity. These vastations were Henry Sr.’s bequest. Some forty years before, at the black bottom of his own despair, a foul, hunched creature appeared before Henry Sr.’s fireplace, gibbering at him and goading him to die. Henry Sr.’s vastation, in his recounting, was a vision of evil made flesh. What William saw was a vision of his future self: a body with the soul scooped out, a brittle human rind.

William’s vastation followed a series of events that had left him, at the age of twenty-four, unmoored, miserable, and alone. His childhood had been shaped by the oppressive whimsy of his father, who had subjected his children to desultory schooling across the globe in the hopes of making them “interesting.” In service to this ideal, William bobbed morosely among vocations. He switched course from painting to chemistry to medicine. Then he dropped out of Harvard Medical School to apprentice himself to the celebrity naturalist Louis Agassiz, who was preparing to journey up the Amazon on a demented quest to disprove Darwin. The expedition was all humidity and hubris. It was there, on the boat, battling bugs and vengeful bowels, that William lost faith in the certitudes of science.

A deflated William returned home. His letters at the time capture a depressed young man with a depressing mustache, leaking sanity while brooding over Hegel. Once athletic, he now lived in his dilapidated body like a squatter. He detailed its collapse in letters to his family: chronic back pain vexing his spirits, “eye trouble” thwarting his reading. His cousin Minnie died during this blighted period. She was brilliant and beautiful and tubercular, and William had loved her. Had been in love with her. He began to ponder suicide.

His father, in similar straits, had been saved by the Christian mysticism of Emanuel Swedenborg. The theologian believed that life on earth was a dialectical struggle between good and evil that culminated, necessarily, in the triumph of the good. William lacked such heartening beliefs. He was both loyal to the materialist conception of the world and tormented by it. In the green-skinned man, William saw the logical end of a life without God, which, he believed, was a life without free will. If the world is only brute matter, then we are hamstrung by our own necrotic flesh, prisoners of our dying bodies.

Then William found the work of the French philosopher Charles Renouvier, author of a tome of neo-Kantian investigations titled Essais du critique generale. “I think that yesterday was a crisis in my life,” he wrote in his diary on April 30, 1870. “I finished the first part of Renouvier’s Essais and saw no reason why his definition of free will—the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts—need be the definition of an illusion…My first of act of free will shall be to believe in free will.”

William’s epiphany was not that the doctrine of free will is true, but that our belief in free will has real consequences for our lives. If we are free, we will know it only by our actions—and we can will ourselves to act only if we believe that we are free.

Renouvier’s essays helped shape the philosophy on which William would labor for the rest of his life. That philosophical framework, known as pragmatism, holds that our beliefs can be measured only by their effects. Like his friend the debauched mathematician Charles Peirce, he believed that the universe is governed by pure chance; the patterns it manifests are evidence only of chance’s operations. What can be truly known is only messy multiplicity, a chaos of particulars, the universe without unity—or the “pluriverse,” as he put it. Rationalism, William held, like creationism before it, seeks to replace this heterodoxy with a soothing artificial order.

Most philosophers, he believed, are doomed by their quest for absolute truths, as no truth is absolute. What we allow to stand for “truth,” then, is closer to usefulness. This is as true of mathematics as it is of metaphysics. The quadratic formula, for instance, is useful in that it lets us predict the trajectory of moving objects. For William, belief in free will was useful in that it kept him from wanting to die. “Thanks to you I have for the first time an intelligent and reasonable conception of freedom,” he wrote to Renouvier two years later. “I am beginning to be reborn to the moral life.”

When Leonora entered her trances, she was no longer, properly speaking, Leonora. She would exit her conscious mind, and one of a rotating cast of ghostly personalities would take over, presiding over her body and her séances. She called these entities her “Spirit Controls.” Some were famous (Johannes Bach), some were familiar (Dr. Hodgson, a deceased colleague of William’s), some were French (Dr. Phinuit, of dubious origins and more dubious accent). All, thought Alice James, were ridiculous. She had always dismissed Spiritualism as the pastime of crooks, spinsters, and “curious spongy minds.” Nothing made her less spiritually inclined than the spirits chattering through her brother’s psychic, forever probing “the squalid intestine of human affairs.”

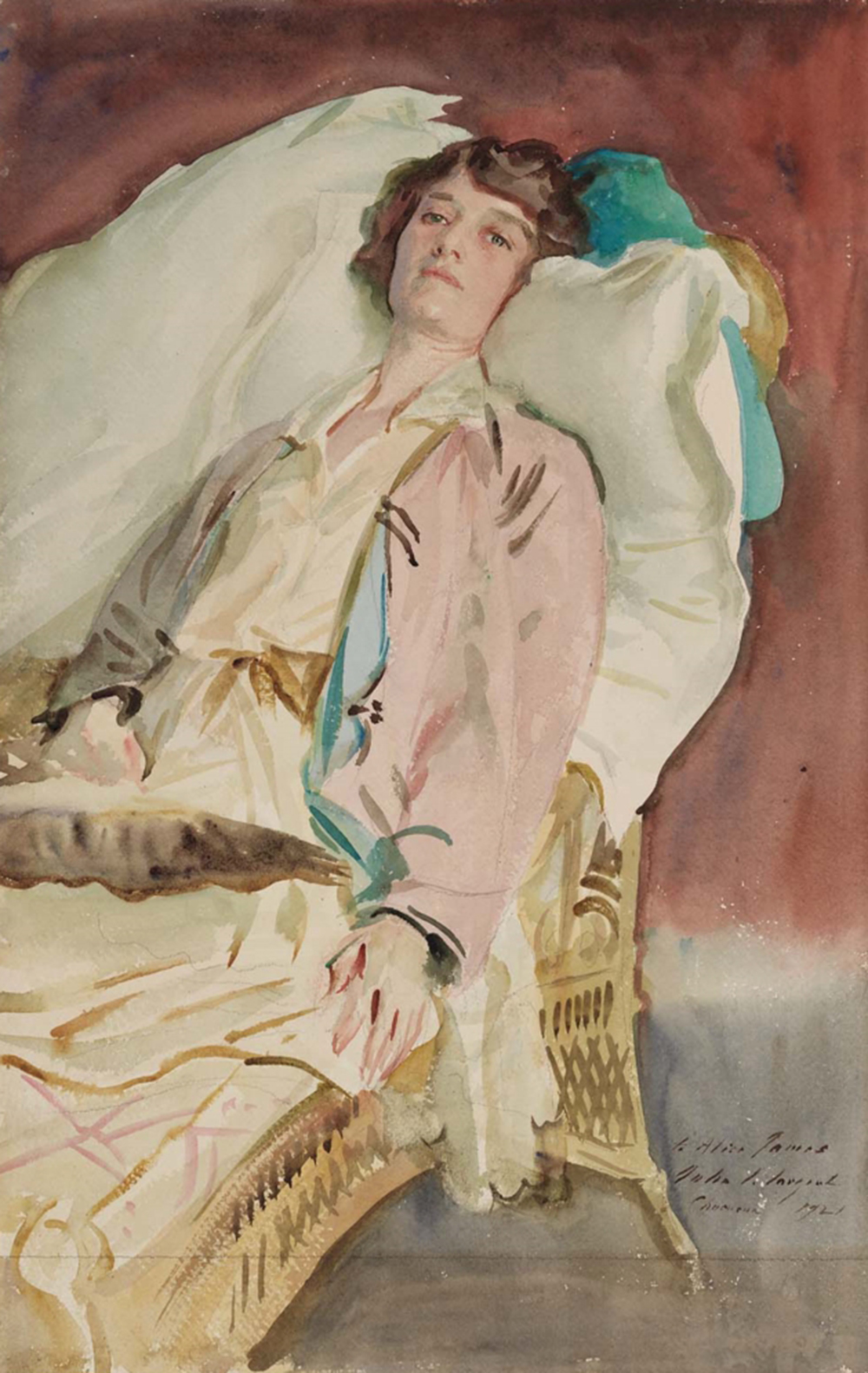

In an early photograph, Alice stares past the camera as though tracking some slow-moving disappointment. Her mouth is thin and parsimonious as a coin slot, her bun pulled snug as a noose. As a standard-bearer in the tradition of reclusive female geniuses, Alice is often compared to Emily Dickinson. While there’s a shade of resemblance between the two, Alice doesn’t radiate the coiled, vaguely libidinal poet energy that Dickinson does in photographs. She looks like a lonely person who stopped going outside, which is exactly how she thought of herself.

Alice, like her brothers, was prone to “nervous” ailments; unlike her brothers, she was groomed for a life of gilded uselessness. For Henry Sr., women were lighthouses: their task was to send out beams of high-watt virtue to beckon men out of moral turpitude. But Alice didn’t beam or beckon. Relentlessly skeptical of herself and others, she smoldered and scrutinized; above all, she suffered, reliant on her father while gently despising him, pining after her friend and possible lover Katherine Loring. She spent much of her life bedridden, trapped in her mind’s transfixing brilliance.

In one particularly vivid letter to a childhood friend, Alice described what she referred to as her “hysterical” attacks:

As I used to sit immovable reading in the library with waves of violent inclination suddenly invading my muscles taking some one of their myriad forms such as throwing myself out of the window, or knocking off the head of the benignant pater as he sat with silver locks, writing at his table, it used to seem to me that the only difference between me and the insane was that I had not only all the horrors and suffering of insanity but the duties of doctor, nurse, and straitjacket imposed upon me too.

These episodes contain all the hallmarks of James vastations: violent dread, moral vertigo, a dissolving self. For the James men, vastations were testaments to the moral strength required to heave themselves out of despair. Alice also saw strength in her ability to endure. But the medical establishment, including William, saw hysteria mostly an expression of “abnormal weakness,” as he wrote in an essay on the subject called “The Hidden Self.”

For the many neurasthenic women like Alice in the nineteenth century, life was a constant struggle to credibly demonstrate their suffering to skeptical doctors. To make a claim about the experience of one’s own body was always, for women, to make a fraught appeal to belief. This was no less true of Alice James seeking treatment for her nervous invalidism than it was of Leonora Piper describing her spiritual telephone. When doctors found a tumor in Alice’s breast, she was filled with “positive glee.” No longer would she have to prove her pain to anyone.

After thirty-odd years of expressing comic disdain for women intellectuals—and of signing letters to her brothers as “your idiotoid sister”—Alice began keeping a diary. This was no minor hobby. She poured a life’s worth of banked genius into a volume of spendthrift, perfect prose and told Katherine Loring to publish it when she died. William James was saved by the writing of Charles Renouvier; Alice James was saved by her own. The diary was a revolution in belief, a devotional practice that gave her ownership of her life.

As her biographer Jean Strouse writes, Alice found “in the process of keeping a diary a nascent sense of self, much as William had done in determining that his first act of free will would be to believe in free will.” Her diary was also the embodiment of what William called a “live” belief: an idea that fortifies us and on which we are willing to act. In Alice’s case, the live belief was that her life and her thoughts were worth recording: she was not made, as Henry Sr. thought, to be a wan abstraction of virtue. Our “faculties of belief,” William wrote, “were given to us to live by.” No belief should demand the soul death of the believer.

This isn’t to say, William wearily maintained, that pragmatism liberates us to believe in any soothing falsehood. It instead forces us to contend with the partiality of all belief. As he often emphasized, our beliefs aren’t formed in isolation but complexly networked with one another. Fidelity to this network of prior beliefs, William argued, determines what we hold to be true. So does the “sentiment of rationality”—the feeling of satisfaction when a new conviction snaps neatly into place with the rest of what we believe.

William’s ideas can strike certain minds as vaguely emasculating. Certainly, the “sentiment of rationality” makes serious thought sound puny, precious, sentimental. Pragmatism, Bertrand Russell wrote, frees us to blithely decide that “Santa Claus exists.” Perhaps James’ notion of “live” beliefs seems suspiciously comforting, even alarmingly facile. Truth, we imagine, isn’t anodyne and life-affirming, but elusive and difficult. We don’t speak merely of perceiving the truth, but of confronting it. Such confrontations impress us, perhaps, as feats of moral strength, evidence of intellectual heroism.

But grasping honestly for truth, James knew, doesn’t feel heroic. More often, it feels like holding hands with a psychic while your sister laughs at you. Or like keeping a diary and telling your lover to publish it after you die. To be lonely in your beliefs is to be aware of just how idiotic and infantile, of just how womanish, you seem to so many people. The task for anyone seeking truth is to endure self-doubt—that most feminizing quality—without retreating into brutality or despair. We have no certainties “on our moonlit and dream-visited planet,” William wrote. We have only our “intellectual republic,” our willingness to “delicately and profoundly respect one another’s mental freedom.”

William James was a champion of W.E.B. Du Bois and Alain Locke, a mentor to Gertrude Stein, and an advocate of his few female colleagues at Harvard. He believed in cultural and philosophical pluralism. He did not believe in the political equality of women. Nor, for that matter, did Alice. Both were quietly appalled by the idea of women dirtying themselves with full inclusion the public sphere. But in his writing William articulated what women, and certainly Alice, had always known: that to be believed is power, and so, too, is believing.

What we believe—whether in ghosts, or God, or our own human worth—doesn’t reflect the world but creates it. It shapes the way we act, and so shapes the environment we act upon. By choosing our beliefs, William once wrote, “we are voting for what sort of universe this shall intimately be.” Belief, in other words, is a form of suffrage. When common sense holds your life to be cheap, claiming “live beliefs” isn’t just an act of faith but an act of political courage.

Alice was more courageous in the face of death than anyone William knew. She was still more courageous than he understood. “I knew you have never cared for life,” he wrote to her a few months before she died, with the frankness she always appreciated. Leonora had showed him the “enlargements of the self” possible in trance, suggesting other possibilities for the self after death. “When that which is you passes out of the body,” he wrote, “I am sure there will be an explosion of liberated force until then eclipsed and kept down.” William, who was sure of nothing—who had built a system of belief on a bedrock of doubt—was somehow sure of this.

That craving for “enlargements of the self” was William’s truest religious impulse. Since his vastation, he dreamed of escaping selfhood into a greater amplitude of being. He never quite believed in God, but he had come to believe in transcendence. The longing for it gave his prose, with its plainspoken grace and offhand beauty, the quality of prayer. But Alice wasn’t interested in transcending the self. She was content with having one. “When I am gone, pray don’t think of me simply as a creature that might have been something else,” she wrote to William. She had no need for spirit realms or psychics. “I hope the dreadful Mrs. Piper,” she wrote in her diary, “isn’t set loose upon my defenseless soul.”